Course

Bladder Cancer Screening and Detection

Course Highlights

- In this Bladder Cancer Screening and Detection course, we will learn about the high-risk populations and typical age range for bladder cancer screening.

- You’ll also learn the recommended screening methods and any important differences in diagnostic ability.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the usual sequence of events from symptom onset through a definitive diagnosis of bladder cancer.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2

Course By:

Brittane L. Strahan MSN, RN, CCRP

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

This section will include a brief overview of the frequency of bladder cancer in the United States. Early detection will be briefly discussed in terms of importance and objectives.

The urinary bladder is composed of a strong muscular layer and special “transitional” cells that expand, and contract as required to store and empty urine. According to the National Cancer Institute, bladder cancer is more common in men than women and white ethnicities versus black or other minority populations.1 Risk increases with age (especially over age 60) and certain other modifiable lifestyle factors such as smoking and other carcinogen exposures. There is also a small proportion of genetically influenced cases, including those associated with other genetic syndromes.

Worldwide, in the hierarchy of cancer prevalence, bladder cancer ranks ninth among men and seventeenth in women.6 Specifically in the United States, an individual has a two percent chance of developing bladder cancer in their lifetime based on data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.9

Importance of Early Detection

Bladder cancer typically has a good five-year survival rate (about 80 percent) (9); however, as with any chronic medical condition, the earlier it is identified and treated, the better the outcome. If identified in the non-muscle invasive stage the treatment differs from a more advanced and invasive cancer. Likewise, widespread cancer requires much more intensive treatment than either a non-invasive or limited invasive stage (12).

The main objective of screening is to facilitate early detection. Typically, screening is only done when a specific symptom (such as hematuria, changes in urination, or pelvic pain) is present. All of these symptoms should prompt a timely evaluation while certain other “alarm” symptoms should be evaluated urgently.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What common demographic features can indicate a higher risk for bladder cancer?

- Is there a component of modifiable risk associated with bladder cancer?

- How does earlier detection affect treatment and overall outcome?

- What are two symptoms that could indicate bladder cancer?

Understanding Bladder Cancer

This section will include a thorough definition of bladder cancer (what it is and how it develops) in addition to the various types. Modifiable risk factors will be discussed in terms of their effect on development. Finally, a brief overview will be given of genetic risk.

Definition and Types of Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer occurs when the cells of the bladder mutate and grow (18, 21). Initially, abnormal growth begins on the cells lining the inside of the bladder. As the tumor progresses, it can invade through the muscular wall. If diagnosed at a very late stage, invasion into the abdominal cavity, or even widespread metastasis, may be observed. (7)

Typically, in about 90 percent of cases, bladder cancer occurs in the “transitional” or urothelial cells lining the bladder. These cells swell and shrink with the amount of urine present. Not only do these cells line the bladder but they also line the rest of the urinary tract. This means that similar cancers can begin elsewhere in the urinary system which may behave similarly to bladder cancer. (19, 20)

Though transitional or urothelial cell carcinoma is the most common histology of bladder cancer, there are several other possibilities. These include adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and small cell carcinoma. Each cell type lines the bladder and serves different functions. Adenocarcinoma occurs in mucus-secreting glandular cells. Squamous cell carcinoma occurs when the flat cells lining the bladder wall are irritated by chronic irritation. Sometimes, not typically in the United States, a parasite known as schistosomiasis can cause chronic infection and inflammation, causing the squamous cell to mutate into a transitional cell. Finally, small cell carcinoma can develop in the neuroendocrine cells of the bladder which are responsible for hormone release into the blood when signaled by the nervous system (16). This malignancy is rare and aggressive, typically found late, and often fatal (10). The specific histology of the tumor may indicate a different likely outcome and require different treatment.

Noninvasive, Non-muscle Invasive, and Muscle-invasive

Bladder cancer can be either limited or invasive and this strongly correlates to how early the tumor is diagnosed. While some cell types are more aggressive, such as small cell carcinoma, most transitional/ urothelial tumor types remain limited to the internal surface of the bladder (8).

Noninvasive tumors, known as carcinoma in situ, are superficial and typically small (17). They have not started to penetrate the inner layer of the bladder and can be easily removed with a transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). A small wire loop is used to grab and remove the tumor. The recovery is typically quick, and the outcome is usually good (15).

Non-muscle invasive cases can usually be treated with localized surgeries, including endoscopic resections and intravesical chemotherapy. Since the tumor is only on the internal bladder surface, there is not usually an indication for systemic treatments.

In more advanced muscle-invasive cases, surgery can be extensive and include a cystectomy. A cystectomy can also be indicated for multiple tumors (7). A radical cystectomy also removes surrounding pelvic organs and requires the creation of a urinary conduit and urostomy. Depending on the advanced stage of the cancer, and if metastasis is present, systemic chemotherapy may also be required to attempt to obtain a good outcome (7, 12).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is the specific type of cell which is typically damaged leading to the development of bladder cancer?

- What are the other cell types which could cause bladder cancer?

- What are the three different forms of bladder cancer?

- Does the type of bladder cancer indicate a different likely outcome?

Risk Factors

There are several modifiable risk factors for bladder cancer. These include smoking, exposure to various chemicals (especially through long-term occupational exposure), and chronic bladder inflammation. All individuals should attempt to mitigate their risk, and providers should be aware of these factors. Individuals with any of these risk factors should be considered to be more than “average risk” and receive appropriate screenings. Family history and genetics play a role as well so ascertaining this information is critical.

Smoking

Smoking is the most common risk factor for the development of many health conditions including bladder cancer. A heavier smoking history poses a risk as does a longer smoking history. Because tobacco is inhaled, enters the bloodstream, and filters through the kidneys into the bladder, its contact with bladder cells can cause permanent damage. Risk reduction begins with quitting and continues for as long as the cessation does. (8, 21)

Chemical exposure

Certain chemicals (aromatic amines), especially those used in the paint/dye, textile, rubber, printing, and leather industries, have been directly linked to an increased risk for bladder cancer. Several other occupations, including truck drivers, firefighters, hairdressers, and machinists, have also been shown to be more likely to develop bladder cancer due to similar chemicals (2, 8, 1). In cases where someone has both occupational exposure and a history of smoking, their risk is deemed to be high. (2)

Surprisingly, arsenic exposure also increases risk. This is not usually the case in the United States; however, in countries with high levels of arsenic in the water supply, this can be a risk-enhancing agent. However, interestingly, chlorine exposure via drinking water can also increase the risk of bladder cancer. This is important to consider since many areas in the United States treat their water supply with chlorine to minimize water-borne illnesses. (2, 8, 1)

Chronic bladder inflammation

Chronic urinary infections can also wreak havoc on the cells of the bladder, causing lasting damage and potential malignancy. This inflammation is not limited to urinary infections but inflammation from stones or medications. Chronic urinary catheterization, as may be required in cases of an enlarged prostate or spinal cord injuries with urinary retention, can also cause inflammation and increase the risk of developing cancer. Usually, in cases where a history of inflammation is thought to be the cause, the histology of the malignancy is identified as squamous cell carcinoma. (2, 8, 1, 21)

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic worm infection, more common in the Middle East and Africa, which also causes inflammation and potentially squamous cell bladder cancer. This is not seen frequently in the United States since schistosomiasis is not typically present in the United States. (2,8,1)

Other risk factors

There are a few other risk factors that do not fall into one of the above categories. These include a history of taking certain medications (including pioglitazone, which is used to control blood sugar) and dehydration from low water intake. Previous chemotherapy, such as cyclophosphamide or ifosfamide, or pelvic irradiation have also been shown to increase risk in some research studies. (2,8,1)

As previously mentioned, being assigned male at birth (3:1 ratio male: female), of white ethnicity (twice as likely as other ethnicities), or over the age of 55 also increases risk. While these are not modifiable, being aware of an increased risk may prompt an individual to pay more attention to and minimize their modifiable risks. (8,2)

Urinary tract cancers can occur in various parts of the urinary tract and a previous history of urothelial cancer predisposes an individual to future urothelial cancers. These may arise at the site of a previous cancer, a different site within the same urinary organ, or a different organ entirely. Anyone with a previous history of urothelial cancer should maintain close follow-up with their healthcare team. (2)

Finally, congenital bladder anomalies may increase one’s risk of developing bladder cancer. During fetal development, the urachus (a connection between the umbilicus and bladder) facilitates the drainage of urine from the fetal bladder. As development continues, the urachus becomes the median umbilical ligament (16).

In rare cases, when the urachus does not transition from a urine-draining conduit to the median ligament, adenocarcinoma may develop from the glandular cells. However, this is exceedingly rare and only accounts for about one percent of bladder cancers. Another congenital anomaly, exstrophy (in which the bladder and abdominal wall fuse, leaving the internal surface of the bladder exposed outside of the body), also significantly increases risk. This defect is closed shortly after birth but predisposes one to urinary tract infections and cancers throughout their lifetime. (2)

Genetic predisposition

Family history can be a strong predictor of cancer risk. Not only is genetics important to consider but family members may be exposed to similar toxins which increase risk.

While most urothelial cancers are not genetically linked, several genes have been linked to an increased risk for bladder and other urinary cancers. These include GSTM1 and NAT2 which code for enzymes required to break down certain chemicals. When these genes are mutated, and the resultant enzymes are faulty, detoxification does not occur as it should and increases the risk of bladder cancer.

Several other genetically linked syndromes appear to increase the risk of bladder cancer as well. Mutations in the RB1 (retinoblastoma) gene cause childhood ocular cancers and increase the risk for future urinary tract cancers. PTEN is mutated in Cowden syndrome and correlates highly with the development of breast and/ or thyroid cancers. However, the risk for urinary tract cancers is also elevated. Finally, Lynch syndrome (linked to colon, pancreatic, breast, and endometrial cancer) has also been correlated with an increased risk for bladder cancer. (2)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do smoking and chemical exposure increase the risk of developing bladder cancer?

- Why does chronic bladder inflammation make it more likely that a person will develop bladder cancer?

- What are two other risk factors for bladder cancer development?

- How does genetics play a role in the development of bladder cancer?

- What is one genetic syndrome that increases the risk of bladder cancer?

Screening Guidelines

This section will include the most current screening guidelines for the United States. Risk will be stratified with a special focus on age. The various screening tests will be reviewed including the technique and the usual progression of testing. Finally, the recommended frequency of screenings will be identified.

Currently, there is no routine screening guidance for Americans at average risk of developing bladder cancer if they are not currently displaying concerning symptoms. Average risk is defined as not meeting any of the known risk factors, including exposure, smoking, history of frequent urinary infections or inflammation, or having a personal or family history of bladder cancer. Since age, male gender, and ethnicity are linked to increased risk, these factors should be considered with routine preventative care. (5,12,14)

Patients who have known risk factors or are symptomatic are stratified based on those unique criteria.

Typically, low and intermediate-risk patients are screened when microhematuria is present. Risk stratification is determined based on age (female- <50 or 50-59; male- <40 or 40-49), smoking history (zero – <10 pack-years or 10-30 pack-years), red blood cells [RBC] on urinalysis <10/ high-powered field [HPF] or 11 – 25 RBC/HPF), and the presence of risk factors.

For both low and intermediate-risk patients, a urinalysis should be followed up with an ultrasound of the urinary tract (kidney, ureters, and bladder) and a cystoscopy. In the case of a low-risk patient, a repeat urinalysis in six months may be a reasonable alternative to ultrasound and cystoscopy.

(4,5,12)

High-Risk Populations

High-risk populations are those who have a positive history of smoking (>30 pack-years), known hazardous exposures, a previous urothelial malignancy, frequent urinary infections, or a genetic predisposition. Those over 60 years old with microhematuria are considered to be high-risk regardless of other factors. Gross hematuria or urinalysis showing >25 RBC/HPF also meets this criterion.

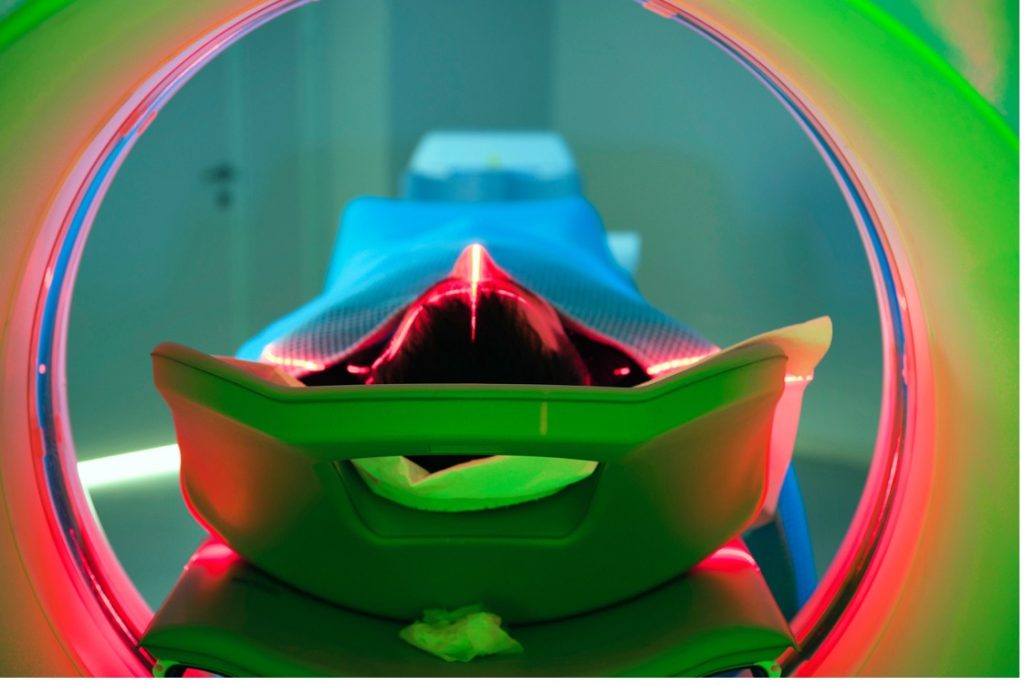

In the case of a high-risk individual, urinalysis should be followed up with a computed tomography (CT) urogram (with contrast) and a cystoscopy. If contrast is contraindicated, the test can be performed without but may not be as useful in which case other tests may be considered. (4,5,12)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are the routine screening guidelines for an average-risk person?

- What finding should prompt further evaluation for urinary malignancy?

- What are the differences in criteria between low and intermediate risk?

- What diagnostic test is used for high-risk screening that is not immediately used for those of lower risk?

Recommended Screening Methods

There are several recommended tests to evaluate bladder cancer. Ranging from non-invasive to invasive, testing decisions should be made based on clinical presentation and individual risk. The initial screening can be done via a urinalysis with cytology. Further testing can be pursued based on those results.

Urinary cytology

Urinalysis and cytology review the cells present in a urine sample for number and structure. Red and white blood cells may be indicative of infection, inflammation, and/ or malignancy. Trace or gross hematuria may also indicate an infection or cancer. If an infection is suspected, a culture can be used to determine the exact pathogen and appropriate treatment. While cytology is a useful tool, it requires a great deal of observational skill from the pathologist, especially in the case of a lower-grade cancer. (12,15,21)

Cytology is useful for following carcinoma in situ, which may be less apparent on cystoscopy, and is also a good surveillance tool for patients with a history of treatment for bladder and other urinary tract malignancies. (4,5,12,15)

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy is considered the “gold standard” examination to diagnose bladder malignancy. However, carcinoma in situ or other low-grade malignancies may be missed especially if they are superficial or flat. Similar to a colonoscopy, a cystoscopy is considered minimally invasive and highly sensitive.

This test can be done in the outpatient setting or the operating room. While examining the bladder with the cystoscope (which may be either flexible or rigid) biopsies can be collected and sent for histopathology. This test is the recommended follow-up exam for any individual meeting the low, intermediate, or high-risk stratification.

“Blue light” cystoscopy is an enhanced screening test that can better visualize in situ or low-grade malignancies when compared to a standard cystoscopy. International guidelines now recommend a “blue light” cystoscopy as the preferred method of imaging for initial diagnosis and follow-up.

Narrow-band imaging is another specialized type of cystoscopy that can help identify changes in the bladder mucosa through digital enhancement. This is a highly specialized modality and requires additional equipment.

(12)

Urinary Biomarkers

Cells in the bladder may secrete specific markers in response to malignancy. Likewise, other cells in the body, such as those in the immune system, may release markers in response to cancer. The presence of these markers can indicate cancer.

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) testing can determine if there are genetic abnormalities in chromosomes 3, 7, or 17 (aneuploidy), and a loss of genes on the short arm of chromosome 9. Any of these genetic mutations increase the risk of developing urinary tract cancers. FISH testing can be useful in the correct context but is very expensive and can produce false negative results. Therefore, it is not widely used and not part of the standard guidelines.

Specifically, in primary care, screening for urine biomarkers may be cost-prohibitive.

(5,12,15)

Frequency of Screenings

Since there are no specific recommendations for individuals of average risk, there is no specific timeline for screening. Screening should be done based on symptoms and risk factors. In cases of low, intermediate, or high-risk screenings requiring follow-up testing, this should be conducted at appropriate intervals (i.e., every six months for the low-risk group).

(12)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What other conditions may confound the results of a cytology screening?

- Why is cystoscopy considered the “gold standard”?

- What differentiates the three different cystoscopy methods?

- Why would biomarker testing not typically be done in a primary care setting?

Detection Methods

This section will include a description of symptoms (including “alarm” symptoms), diagnostic testing via imaging and biopsy, and the importance of follow-up exams.

Symptoms

Several key symptoms should prompt a timely evaluation by the primary care physician. These include hematuria, increased urinary frequency, painful urination (including a burning sensation), and urinary urgency. Depending on the location or size of the tumor there may be a weak or almost non-existent stream of urine. Of course, these symptoms can be indicative of several different urinary conditions including stones, infection, or kidney disease.

In addition, some “alarm” symptoms prompting immediate evaluation would include unilateral back pain, anuria, lethargy, feelings of weakness, bone pain, or unexplained weight loss. These could indicate a more advanced cancer.

(3)

Diagnostic Testing

Several diagnostic tests can be useful when considering a diagnosis of bladder cancer. These include both imaging exams and biopsy procedures. Typically, a cystoscopy with biopsy will be the first diagnostic test conducted followed by more extensive imaging tests, including CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are three symptoms that could indicate bladder cancer and should be evaluated promptly?

- What are three “alarm” symptoms that should be evaluated immediately?

- What is the typical sequence of diagnostic screening tests?

- Why might ultrasound not be the best diagnostic imaging tool?

- Are there specific circumstances in which an MRI may be chosen over a CT scan?

Imaging Tests

As mentioned above, low and intermediate-risk individuals will be referred to have an ultrasound and cystoscopy. Ultrasound can be used to visualize the kidneys, ureters, and bladder and is fairly accurate in identifying small blockages in addition to measuring bladder wall thickness. It has been noted though that ultrasound may not identify smaller tumors or carcinoma in situ. (4,12)

High-risk patients should be evaluated with either a CT urogram or MRI urogram. CT scans are highly sensitive and create a more detailed picture of the pathological process. They can also show blockages and tumorous growths, whether or not metastasis is present, and determine staging. MRI produces an even more detailed image and is especially helpful in determining and assessing the extent of muscle invasion or lymph node involvement. MRI is also preferred in cases when CT contrast cannot be used (i.e. renal failure).

Intravenous pyelogram testing was previously the standard; however, it is no longer used due to the wide availability of CT or MRI. This test involves a pre-contrast abdominal X-ray followed by several serial X-rays after the injection of intravenous contrast. This allows for imaging capture of the flow of contrast through the entire urinary tract allowing for the visualization of obstructions or masses. Historically, the intravenous pyelogram was very accurate at identifying small tumors and visualizing the upper tract.

Positron-emission tomography (PET) scan is used to assess the extent of metastasis and is more specific than CT. The best use case for a PET scan is before a radical cystectomy and should not be used at the initial diagnosis. PET scans can also be used to monitor disease status in more advanced cases.

(11)

Biopsy Procedures

Biopsies can be obtained during cystoscopy or transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) and are key to determining the exact histology of the tumor and delineating if the tumor is muscle-invasive or not. All abnormal areas should be biopsied to confirm the presence or absence of malignancy. In the case of solid or sessile tumors, random sampling should be done to “map” the tumor. In the case of papillary (protruding) tumors, each stalk should be sampled.

Cold-cup biopsies are the preferred method during a cystoscopy. During a TURBT, a resectoscope is inserted through the cystoscope sheath. The wire loop is used to snare and remove any lesions. (16)

Electrocautery removal is not advised because cautery artifacts may be left at the site.

The location of the tumor and biopsies should be carefully recorded, and this information should be used to monitor for recurrence or progression. To minimize the risk of perforation, care should be taken to maintain an empty bladder which will keep the bladder wall thick and stationary.

Follow-up testing is done to confirm diagnostic findings or to monitor for recurrence or progression of disease after treatment.

(12)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why has the intravenous pyelogram been dropped as the standard imaging modality?

- What is the preferred method of biopsy?

- Why is it important to correctly identify the biopsy sites?

- What is the recommended frequency for follow-up?

Limitations of Screening

This section will include a brief overview of the limitations of screening, including the possibility of false positive and negative results from screening and diagnostic tests. The cost and availability of testing will be evaluated, and the psychological toll of a bladder cancer diagnosis (including false positive and negative results) will be reviewed.

False Positives and Negatives

In the case of bladder malignancies, screening may produce both false positive and false negative results.

False positive results indicate that an individual has a malignancy when, in fact, they do not. In the case of “blue light” cystoscopy, the compound used to create the color variation may be taken up by inflamed cells, tissue that has been treated with intravesical chemotherapy, or resected and may cause a false positive result. This may lead to additional invasive testing and unnecessary treatment. While neither testing nor early treatment has been shown to cause harm on a broad scale, every individual will have different expectations and outcomes.

False-negative results may occur when bladder cancer is not diagnosed on screening tests. This may happen more in cases of carcinoma in situ or low-grade tumors, which are small and more difficult to visualize on cystoscopy or other imaging exams and may not display any abnormalities on cytology. This missed diagnosis may lead to delayed treatment and worse outcomes since the cancer will be more advanced when treatment is sought.

(5,12,15)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What does it mean if a false positive result is obtained?

- Why might a “blue light” cystoscopy lead to a higher rate of false positive tests?

- What are the risks of receiving a false positive or negative result?

Costs and Accessibility

Screening costs and accessibility can vary greatly depending on geographic location. Newer tests, both imaging and tissue testing, may not be available in rural or underserved areas. Likewise, unless referred to a urologist, the patient may be limited to testing available to a primary care physician. (12)

The Psychological Impact of Screening

False positive results can create unnecessary psychological turmoil including anxiety, pain, and fear. On the other hand, false negatives may lead to a later diagnosis and poorer outcomes. Not only can there be a substantial toll on mental health but either erroneous result could lead to decreased trust in the healthcare team or testing modalities.

In addition, physical harm may be unintentionally caused in cases of late treatments or unnecessary diagnostic testing and/or treatments.

Finally, the biggest psychological impact of screening probably comes from receiving a positive cancer diagnosis.

(15)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some of the factors affecting access to screening tests?

- What are the psychological implications of receiving either a false positive or negative result?

- Are there any other risks (not psychological) that may be increased by receiving a false result?

Advances in Screening Technology

This section will include a brief overview of emerging advancements in bladder cancer screening and detection. This will include both biomarker and genetic testing in addition to imaging tests.

Emerging biomarkers and genetic testing

Urinary messenger RNA has been demonstrated to be a useful and emerging tool. This method of urine testing can identify five different bladder cancer genes and is accurately predictive for recurrence. This specific testing modality is still in an investigational phase and is not yet available outside of a clinical trial.

Similar to the use of urinary messenger RNA testing for non-invasive prediction of recurrence, several biomarkers are currently being evaluated in the investigative setting. These are not currently available for use. (12,13)

The newest imaging technique is narrow-band cystoscopy. While this method is approved, it is not widely available. This limited access puts some people at a disadvantage because of its innovative diagnostic method. Utilizing enhanced digital image processing instead of medical contrast compounds, which may be taken up by non-malignant cells, can provide data that is equally as accurate and less confusing if there is chronic inflammation in the bladder. (12)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What urine marker can be used to identify a likely bladder cancer diagnosis?

- Are biomarker tests available in a standard-of-care setting?

- What are the advantages of using the narrow-band cystoscopy method versus the traditional or “blue light” methods?

- What conclusions can be drawn about the importance of the early detection of bladder cancer?

Conclusion

A diagnosis of bladder cancer can be devastating, especially if made late in the disease course. While bladder malignancies are not as common as lung, breast, or colon cancer, they may be both severe and require extensive surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation treatments. The key to mitigating the risk of being diagnosed with bladder cancer is in prevention and minimizing modifiable risk factors such as smoking and chemical exposure.

However, since previous exposures may lead to a malignancy being diagnosed, screening and detection at an earlier stage is key. Hematuria can be a signal that an abnormal bladder process is occurring, and this should signal to both the individual and their provider that further screening is warranted. Both imaging tests and biopsies are required to make a definitive diagnosis. Understanding the pathology and extent of the tumor can then facilitate the design of an appropriate treatment plan. As with all chronic medical conditions, and especially cancer, the sooner the condition is diagnosed, the better the outcome.

References + Disclaimer

- Bladder cancer causes and risk factors—Nci. (2023, February 16). [pdqCancerInfoSummary]. https://www.cancer.gov/types/bladder/causes-risk-factors

- Bladder cancer risk factors | How do you get bladder cancer? (2023). https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/bladder-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

- Bladder cancer screening | Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University. (2022). https://winshipcancer.emory.edu/cancer-types-and-treatments/bladder-cancer/screening.php

- Bladder cancer screening and diagnosis. (2021, August 8). https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/bladder-cancer/bladder-cancer-screening-and-diagnosis

- Bladder cancer screening—Nci. (2023, February 16). [pdqCancerInfoSummary]. https://www.cancer.gov/types/bladder/screening

- Bladder cancer statistics | World Cancer Research Fund International. (n.d.). WCRF International. Retrieved October 13, 2024, from https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/bladder-cancer-statistics/

- Bladder cancer: Symptoms, causes & treatment. (2022, August 26). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14326-bladder-cancer

- Bladder cancer types: Non-muscle invasive (Nmibc) & invasive | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. (n.d.). Retrieved October 13, 2024, from https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/types/bladder/types

- Cancer of the urinary bladder—Cancer stat facts. (n.d.). SEER. Retrieved October 13, 2024, from https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/urinb.html

- Coppola, A., Gatta, T., Pini, G. M., Scordi, G., Fontana, F., Piacentino, F., Minici, R., Laganà, D., Basile, A., Dehò, F., Carcano, G., Franzi, F., Uccella, S., Sessa, F., & Venturini, M. (2023). Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary bladder: Ct findings and radiomics signature. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(20), 6510. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206510

- Intravenous pyelogram (Ivp): Procedure, risks & results. (2022, July 29). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/23578-intravenous-pyelogram

- Leslie, S. W., Soon-Sutton, T. L., & Aeddula, N. R. (2024). Bladder cancer. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536923/

- Mousazadeh, M., & Nikkhah, M. (2024). Advanced bladder cancer detection: Innovations in biomarkers and nanobiosensors. Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research, 45, 100667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbsr.2024.100667

- Noninvasive bladder cancer treatment—Uchicago medicine. (n.d.). Retrieved October 13, 2024, from https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/cancer/types-treatments/bladder-cancer/treatment/localized

- Screening for bladder cancer: Recommendation statement. (2012). American Family Physician, 85(4), 397–399. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2012/0215/p397.html

- Tomiyama, E., Fujita, K., Hashimoto, M., Uemura, H., & Nonomura, N. (2024). Urinary markers for bladder cancer diagnosis: A review of current status and future challenges. International Journal of Urology, 31(3), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/iju.15338

- Transurethral resection for bladder cancer. (n.d.). Retrieved October 14, 2024, from https://nyulangone.org/conditions/bladder-cancer/treatments/transurethral-resection-for-bladder-cancer

- Urachal abnormalities. (n.d.). UCSF Department of Urology. Retrieved October 14, 2024, from https://urology.ucsf.edu/patient-care/children/urachal-abnormalities

- What is bladder cancer? – Nci. (2023, February 16). [pdqCancerInfoSummary]. https://www.cancer.gov/types/bladder

- What is urothelial carcinoma? (2023, January 4). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/6239-transitional-cell-cancer

- Zhu, C.-Z., Ting, H.-N., Ng, K.-H., & Ong, T.-A. (2019). A review on the accuracy of bladder cancer detection methods. Journal of Cancer, 10(17), 4038. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.28989

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate