Course

Connecticut APRN Bundle Part 1

Course Highlights

- In this course, we will learn about how people of minority groups experience healthcare differently than other patients.

- You’ll also learn the risk factors associated with a higher prevalence of mental health diagnoses.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of commonly prescribed opioids for pain management and understand their side effects and indications of use.

About

Contact Hours Awarded:

Pharmacology contact hours included: 5

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

Cultural Competence in Nursing

The purpose of this course is to outline and explore the most common or serious disparities, address ways in which healthcare delivery needs to be adjusted, and start the conversations needed to create a new generation of healthcare that will close these gaps.

Introduction

There is no doubt that modern medicine has made many technological advancements over the last few decades, forging the way for highly intricate diagnostic and treatment methods and improving the quality and longevity of many lives. In order to truly keep up with changing times however, healthcare professionals must consider much more than the technical aspects of healthcare delivery. They must take a closer look and a more conscientious approach to the way in which care is delivered, particularly across a wide variety of demographics and characteristics. Ensuring care is delivered with empathy, respect, and equity, noting and honoring a patient’s differences, is how care transforms from good to truly great. Practicing diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), as well as cultural competence in nursing professions must become a standard.

Health Disparities

When covering cultural competence in nursing, it is vital that a provider knows that each patient is a unique individual. However, there are some characteristics such as race, gender, age, sexual orientation, or disability that can create gaps in the availability, distribution, and quality of healthcare delivered. These gaps can create lasting negative impacts for patients mentally, physically, spiritually, and emotionally and even lead to poorer outcomes than patients not within a special population. Modern healthcare professionals have a responsibility to learn to identify risks, provide sensitive and inclusive care, and advocate for equity in much the same way that they have a responsibility to learn how the human body, medications, or hospital equipment works.

Epidemiology

In order to understand the importance of cultural competence in nursing as well as the best practices for DEI in healthcare, let’s turn to data.

Healthy People 2020 provides a myriad of data that includes countless implications for changes that need to occur in healthcare settings for equitable care of all populations. The data includes statistics such as:

- 12.6% of Black/African American children have a diagnosis of asthma, compared to 7.7% of white children (16).

- The rate of depression in women ages 65+ is 5% higher than that of men of the same age, across all races (16).

- Teenagers and young adults who are part of the LGBTQ community are 4.5 times more likely to attempt suicide than straight, cis-gender peers (16).

- 16.1% of Hispanics report not having health insurance, compared to 5.9% of white populations (16) .

- The national average of infant deaths per 1,000 live births is 5.8. The rate for Black/African American infants is nearly double at 11 deaths per 1,000 births (16).

- 12.5% of veterans are homeless, compared to 6.5% of the general U.S. population (16).

Additional disparities are seemingly endless and point unquestionably to the fact that cultural competence and DEI awareness is no longer something that healthcare professionals can be uniformed about. The purpose of this course is to outline and explore the most common or serious healthcare disparities, address ways in which healthcare delivery needs to be adjusted, and start the conversations needed to create a new generation of healthcare professionals that will close these gaps.

The importance of understanding DEI best practices in the health setting, as well as possessing cultural competence in nursing, is vital in making positive changes for all populations.

Race & Ethnicity

One of the most significant disparities in healthcare, and the one garnering the most attention and campaigns for change in recent years, is race and ethnicity. However, when covering the best practices for cultural competence in nursing, it is essential that we go over this topic. Studies in recent years have revealed that minority groups, particularly Black Americans, are sicker and die younger than white Americans. Examples include:

Current data shows that Black men are more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer and 2.5 times more likely to die from it than their white peers. A 2019 study through University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center explored prostate cancer outcomes when factors such as access to care and standardized treatment plans were controlled. They found that outcomes were comparable and Black men experienced similar mortality to the white men in the study, implying that they did not “intrinsically and biologically harbor a more aggressive disease simply by being Black” (11).

A 2020 study found that Black individuals over age 56 experience decline in memory, executive function, and global cognition at a rate much faster than their white peers, often as much as 4 years ahead in terms of cognitive decline. Data in this study attribute the difference to the cumulative effects of chronically high blood pressure, more likely to be experienced by Black Americans (20).

Black women experience twice the infant mortality rate and nearly four times the maternal mortality rate of non-Hispanic white women during childbirth. One in five Black and Hispanic women report poor treatment during pregnancy and childbirth by healthcare staff. Studies indicate that in addition to biases within the healthcare system, some of these poor outcomes may also be attributed to cumulative effects of lifelong inferior healthcare (1).

Lack of health insurance keeps many minority patients from seeking care at all. 25% of Hispanic people are uninsured and 14% of Black people, compared to just 8.5% of white people. This leads to lack of preventative care and screenings, lack of management of chronic conditions, delayed or no treatment for acute conditions, and later diagnosis and poorer outcomes of life threatening conditions (4).

Emerging data indicates that hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 are disproportionately affecting Black and Hispanic Americans, with Black people being 153% more likely to be hospitalized and 105% to die from the disease than white people. Hispanic people are 51% more likely to be hospitalized and 15% more likely to die from COVID-19 than white people (21).

The potential reasons are many, from genetics to environmental factors such as socioeconomic status, but data repeatedly shows that these factors are not enough to account for the disproportionate health outcomes; it eventually comes down to inequity in the structure of the healthcare systems in which we all live. For example:

Medical training and textbooks are mostly commonly centered around white patients, even though many rashes and conditions may look very different in patients with darker skin or different hair textures (13).

There is also a lack of diversity in physicians; in 2018, 56.2% were white, while only 5% were Black and 5.8% Hispanic. More often than not, patients will see a physician that is a different race than they are, which can mean their particular experiences as a minority person, and how that relates to their health, are not well understood by their physician (2).

While the Affordable Care Act increased the number of people who have access to health insurance, minority patients are still disproportionately uninsured, which leads to delayed or no care when necessary (4).

Minority patients are also often those living in poverty, which goes hand in hand with crowded living conditions and food deserts due to outdated zoning laws created during times of segregation. This means less access to nutritious foods, fresh air, or clean water which has overall negative effects on health (21).

Potential solutions to these problems are in the works across many fronts, but the breaking down and resetting of old institutions will likely require change on a broader, political level.

Medical school admission committees could adopt a more inclusive approach during the admission process . For example, paying more attention to the background and perspectives of their applicants and the circumstances/scenarios in which they came from as opposed to their involvement in extracurriculars (or lack of) and former education. Incentivizing minority students to choose careers in healthcare as well as investing in their retention and success should become a priority in the admissions process (13). This is one of the main drivers and only possible paths to having minority representation in healthcare systems nationwide.

Properly training and integrating professionals like midwives and doulas into routine antenatal care and investing in practices like group visits and home births will give power back to minority women while still giving them safe choices during pregnancy (1).

Universal health insurance, basic housing regulations, access to grocery stores, and many other socio-political changes could also work towards closing the gaps in accessibility to quality healthcare and may vary by geographic location.

Understanding the inequalities that currently exist in the healthcare system for those of minority races is essential in this lesson on cultural competence in nursing.

It is the healthcare provider’s duty to be an advocate for the patient, and the ability to recognize and identify practices that are not diverse, equitable, or inclusive to all races and ethnicities is vital in improving care delivery methods.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What does cultural competence in nursing mean to you?

- When you have a medical appointment, how do you get there?

- How do you pay for the services?

- Do you have a provider that you feel understands your unique needs?

- How do you think the answer to those questions might vary for someone of a different race living in your same town?

LGBTQ

Another highly at risk group for healthcare inequity are members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transexual, and Queer (LGBTQ) community. When practicing cultural competence in nursing, the provider must become aware of how vulnerable this population is, especially in healthcare settings. Risks and examples of disparities within the LGBTQ community include:

- Youth are 2-3 times more likely to attempt suicide

- More likely to be homeless

- Women less likely to get preventative screenings for cancer

- Women more likely to be overweight or obese

- Men are more likely to contract HIV, particularly in communities of color

- Highest rates of alcohol, tobacco, and drug usage

- Increased risk of victimization and violence

- Transexual individuals are at an increased risk for mental health disorders, substance abuse, suicide, and more likely to be uninsured than any other LGB individuals (17)

Current data suggests that most of the health disparities faced by this group of people are due to social stigma, discrimination, lack of access or referral to community programs, and implicit bias from providers leading to missed screenings or care opportunities.

Support systems and social acceptance are strongly linked to the mental health and safety of these individuals. Lack of support and acceptance in the home, workplace, or school leads to negative outcomes. Also, a lack of social programs to connect LBGTQ individuals to each other and build a community of safety and acceptance creates further gaps.

There is currently still discrimination in access to health insurance and employment for this population which can affect accessibility of quality health care as well as affordable coverage.

Following this, a compilation of recent data showcases that there are significant issues with the quality and delivery of care provided to those in the LGBTQ community. This data includes:

- In a 2018 survey of LGBTQ youth, 80% reported their provider assumed they were straight and did not ask (18).

- In 2014, over half of gay men (56%) who had been to a doctor said they had never been recommended for HIV screening (14).

- A 2017 survey of primary care providers revealed that only 51% felt they were properly trained in LGBTQ care (25).

Although it is unclear as to whether this data stems from a lack of education or social awareness from the provider, it is evident that change needs to be made.

In order to improve these conditions and close the gap for LGBTQ individuals, much can be done on the community level and in medical training:

- Community programs should be available to create safe spaces for connection and acceptance.

- Laws and school policies can focus on how to prevent and react to bullying and violence against LGBTQ individuals.

- Cultural competence training in medical professions needs to include LGBTQ issues.

- Data collection regarding this population needs to increase and be recognized as a medical necessity, as it is largely ignored currently.

It is essential for providers to stay up-to-date on changes and health trends among the LGBTQ populations, as healthcare delivery methods may require adjustments over time; this is critical when learning about cultural competence in nursing.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Think about a patient you have cared for that did not come in with a significant other. Did you make any assumptions about that client’s sexual orientation or gender identity?

- Would there have been different risk screenings you needed to perform if they were part of the LGBTQ community?

- Think about what you know about psychological development during the teenage years. Why do you think suicide risk is so much higher among LGBTQ youth?

- Why do you think a strong support system is protective against suicide in this population?

Gender & Sex

Gender and sex play a significant role in health risks, conditions, and outcomes due to a combination of factors, including biological, social, and economic elements. Among the differences in health data related to gender are:

- Women are twice as likely to experience depression than men across all adult age groups (7).

- About 12.9% of school aged boys are diagnosed and treated for ADHD, compared to 5.6% of girls, though the actual rate of girls with the disorder is believed to be much higher (9).

- A 2010 study showed men and women over age 65 were about equally likely to have visits with a primary care provider, but women were less likely to receive preventative care such as flu vaccines (75.4%) and cholesterol screening (87.3%) compared to men (77.3% and 88.8% respectively) (5).

- In the same study, 14% of elderly women were unable to walk one block, as opposed to only 9.6% of men at the same age (5).

- Heart disease is the leading cause of death in women, yet women are shown to have lower treatment rates for heart failure and post heart attack care, as well as lower prevalence but higher death rates from hypertension than men (6).

It is also important to differentiate the difference between gender and sex when practicing cultural competence in nursing.

Sex is the biological and genetic differentiation between male and female, whereas gender is a social construct of difference in societal norms or expectations surrounding men and women. For someone looking to better practice cultural competence in nursing and provide both equitable and inclusive care, it is essential that you know this differentiation.

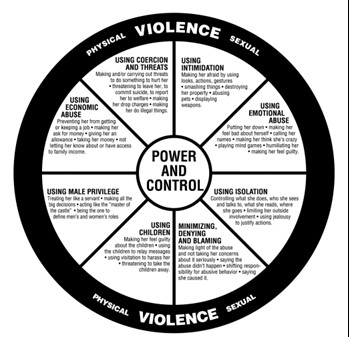

Some health conditions are undeniably attributable to the anatomical and hormonal differences of biological sex; for example, uterine cancer can only be experienced by those who are biologically female. But many of the inequalities listed above disproportionately burden women due to the social and economic differences they experience in society; for example, 1 in 4 women experience intimate partner violence as compared to 1 in 9 men (22).

What are the reasons for this? A lot of it has to do with how women are perceived in society, how their symptoms may present differently than male counterparts, or how their symptoms are presented to and received by medical professionals.

- For centuries, any symptoms or behaviors that women displayed (largely mental health related) that male doctors could not diagnose fell under the umbrella of hysteria. The recommended treatment for this condition was anything from herbs, isolation, sex, or abstinence and it is only in the last one hundred years or so that more accurate medical diagnoses began to be given to women. Hysteria was not deleted from the DSM until 1980 (27).

- The Cameron study found that women were more verbose in their encounters with physicians and may not be able to fit all of their complaints into the designated appointment time, leading to a less accurate understanding of their symptoms by their doctor (5).

- The same study also indicated that women tend to have more caregiver responsibilities and feel less able to take time off for hospitalizations or treatments (5).

- Symptoms of mental health disorders like ADHD may look different in girls than in boys. Girls who are having difficulty focusing may be categorized as “chatty” or a “daydreamer” by teachers, whereas boys are more likely to draw attention for being hyperactive or disruptive, when both are actually experiencing symptoms of ADHD and could benefit from treatment (10).

In order to close these gaps and ensure equitable care for men and women, the way that teachers, doctors, and nurses view and respond to girls and women must be adjusted.

- Children who are struggling in school should be looked at more comprehensively and the differences in learning styles widely understood.

- Screening questionnaires and standard preventive care used when caring for clients in primary care.

- Social services should be utilized to help determine if women are pushing aside their own healthcare needs due to responsibilities at home.

- Medical professionals must be trained in the history of inequality among women, particularly in regards to mental health, and proper, modern diagnostics must be used.

- The differences in communication styles of men and women should be understood when caring for patients.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Think about a patient you cared for recently and how they communicated their needs and symptoms to you. How do you think this might have differed if they had been a different gender?

- In what ways do you think the history of “hysteria” in women may still be subtly present today?

Religion

Religion can impact when patients seek care, which treatments they will participate in, and how they perceive their care. Even advanced technology in healthcare can be perceived as unsatisfactory if it violates religious preferences for patients, so it is very important for healthcare professionals to be aware of certain religious preferences to provide the most competent and sensitive care possible. Consequences of culturally incompetent care include:

- Negative health outcomes due to not participating in care that violates their religious beliefs.

- Patient relationships with healthcare professionals can suffer if they feel disrespected or misunderstood, causing patients to delay or avoid seeking care altogether.

- Dissatisfaction with care which can even lead to long term trauma surrounding major events like birth, death, or chronic disease if a patient felt uninvolved or disrespected in their care (26).

There are many religions with different practices and ordinances, but we will cover some of the more major and common implications regarding health practices here. Typically, views on pregnancy/birth, death, diet, modesty, and treatment for illness are the most important areas for healthcare professionals to understand. Providers must continue to educate themselves on the practices and preferences of various religions; it is essential in practicing cultural competence in nursing.

Disclaimer: Please note that each religion has many variations and that not all practices may be the same. The following information has been sourced from “Cultural Religion Competency in Clinical Practice,” written by Drs. Diana Swihart, Siva Naga S. Yarrarapu, and Romaine L. Martin (26).

Buddhism

Study and meditate on life, cause and effect, and karma, working towards personal enlightenment and wisdom. They believe the state of mind at death determines their rebirth and prefer a calm and peaceful environment without sedating drugs. Have ceremonies around birth and death. Their diet is usually vegetarian (26).

Christian Science

Based on the belief that illness can only be healed through prayer. They typically choose spiritual healing for disease or illness prevention and treatment. Often refuse vaccines and delay treatment for acute illnesses. They avoid tobacco and alcohol but have no other dietary restrictions (26).

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints/Mormon

Heavily family-oriented, involvement of family in major health/life events is important. Strict abstinence outside of heterosexual marriage. Fasting required monthly, exempt during illness. Blood or blood products are accepted. Abortion is prohibited unless it as a result of a rape or the mother’s life is in danger. Two elders present for the blessing of those ill or dying (26).

Hinduism

Centers on leading a life that allows you to reunite with God after death. Believes in reincarnation and so the environment around dying people must be peaceful. Presence of family and priest during end of life is preferable. After death, the body is washed and not left alone until cremated. Euthanasia is forbidden. Often vegetarian and the right hand is used for eating (26).

Islam

Belief in God and the prophet Abraham. Prayer is required five times daily. Observe Ramadan, a month of fasting and abstinence during daylight (children and pregnant women are exempt from fasting). Autopsies should only be performed if legally necessary. Must eat clean, halal, food and excludes pork, shellfish, and alcohol. Female patients require female healthcare providers. Abortion is prohibited (26).

Jehovah’s Witness

Belief destruction of the present world is coming and true followers of God will be resurrected. Do not celebrate birthdays or holidays. Believe death is a state of unconscious waiting. Euthanasia prohibited. Refuse blood and blood products. Abortion is prohibited. Pregnancy through artificial means (IUI, IVF) is prohibited (26).

Judaism

Belief in all powerful God and varying levels of interpretation/observance of laws and traditions. Cremation is discouraged or prohibited. Prayer is important for the sick and dying, after death the body is not left alone. Must eat kosher foods, excludes pork. Amputated limbs must be saved and buried where the person will one day be buried. Abortion allowed in certain circumstances (26).

Protestant

Christian faith formed in resistance to Roman Catholicism. Autopsy and organ donation are acceptable. Euthanasia is not acceptable. No restrictions on diet or traditional western medicine treatments (26).

Roman Catholicism

Christian faith steeped in tradition and observance of sacraments. Clergy present at end of life for the sacrament of Last Rites. Avoid meat on Fridays during Lent. Mass and Communion on Sundays is an obligation and they may require a clergy member visit during hospitalization. Abortion and birth control (other than natural family planning) prohibited. Artificial conception discouraged. Newborns with a grave prognosis need to be baptized (26).

In order to better practice cultural competence in nursing and improve the quality of care given that respects a patient’s faith and religious boundaries, one should focus on:

- Understanding basic differences and preferences with various religions and providing training for staff.

- Encouraging family to participate in health decision making where appropriate.

- Providing interpreters where needed.

- Promoting an environment that allows for clergy, healers, or other religious figures of comfort to visit and participate in care if desired.

- Providing dietary choices that are considerate of religious dietary preferences.

- Recruiting staff that are minorities or of various religions.

- Respecting a client’s views on controversial topics such as pregnancy/birth, death, and acceptance or declining of treatments even if it conflicts with staff members own beliefs (26).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Imagine you work on a maternity unit and are caring for a new mother who observes the Islamic faith. What needs might she have in order to feel respected and comfortable with her care?

- You are caring for a patient on the critical care unit who is a Jehovah’s Witness. In what ways might this client’s faith impact their care?

Age

As the Baby Boomer generation ages, there is a growing number of older adults in the U.S. In 2016, there 73.6 million adults over age 65, a number which is expected to grow to 77 million by 2034. As of 2016, 1 in 5 older adults reported experiencing ageism in the healthcare setting (24). As the number of older adults needing healthcare expands, the issue of ageism must be addressed. For providers looking to improve cultural competence in nursing practices, it is vital that ageism is addressed, as it flies under the radar. Ageism is defined as stereotyping or discrimination against people simply because they are old. Ways in which ageism is present in healthcare includes:

- Dismissing a treatable condition as part of aging.

- Over-treating natural parts of aging as though they are a disease.

- Stereotyping or assuming the physical and cognitive abilities of a patient purely based on age.

- Providers being less patient, responsive, and empathetic to a patient’s concerns or even talking down to patients or not explaining things because they believe them to be cognitively impaired.

- Elderly patients may internalize these attitudes and seek care less often, forgo primary or preventative screenings, and have untreated fatigue, pain, depression, or anxiety

- Signs of elder abuse may be ignored or brushed off as easy bruising from medication of being clumsy (24).

There are many reasons why ageist attitudes in healthcare may occur, including:

- Misconceptions and biases among staff members, particularly those that have worked with a frail older population and assume all elderly people are frail.

- Lack of training in geriatrics and the needs and abilities of this population.

- Standardizing screenings and treatments by age may help streamline the treatment process but can lead to stereotyping.

- Changing this process and encouraging an individual approach may be resisted by staff and viewed as less efficient.

In order to combat ageism and make sure healthcare is appropriately informed to provide respectful, equitable care:

- Healthcare professionals can adopt a person-centered approach rather than categorizing care into groups based on age.

- Facilities can adopt practices that are standardized regardless of age.

- Facilities can include anti-ageism and geriatric focused training, including training about elder abuse.

- Healthcare providers can work with their elderly patients to combat ageist attitudes, including internalized ones about their own abilities (24).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for two patients of the same age who seemed drastically different in their overall health and independence? Why do you think that is?

- Think about your own attitudes about older adults. What biases or assumptions do you have about the cognitive and physical abilities of people who are 65? 75? 85?

Veterans

Veterans are a unique population that face many health concerns unique to the conditions of their time in service. Much of veteran health care is provided through the Veteran Affairs (VA) facilities, a nationalized form of healthcare involving government owned hospitals and clinics and government employed healthcare professionals. Again, the purpose of this course is to educate providers on how to practice cultural competence in nursing; however, let’s introduce the disparities found within this population by utilizing a few statistics.

- 1 in 5 veterans experience persistent pain and 1 in 3 veterans have a diagnosis related to chronic pain (8).

- Approximately 12% of veterans experience symptoms of PTSD in their lifetime, compared to 6% of the general population and 80% of those with PTSD also experience another mental health disorder such as anxiety or depression (8).

- More than 1 out of every 10 veterans experiences some type of substance use disorder (alcohol, drugs), which is higher than the rate for non-veterans (8).

- In 2019, around 9% of homeless adults were veterans (28).

- Veterans account for 20% of all suicides in the U.S, despite only about 8% of the U.S. population serving in the military (8).

- Disparities also exist within the veteran population and veterans who are a minority race or female experience these issues at an even higher rate.

- For example, veteran women are twice as likely to experience homelessness than veteran men (28).

The causes of these troubling issues for veterans are multifaceted; some of it relates to the nature of work in the U.S. Military and increased exposure to trauma (particularly with those involved in combat), and some of it relates to the care of veterans and their mental health during and after their service.

- 87% of veterans are exposed to traumatic events at some point during their service (8).

- Current data suggests fewer than half of eligible veterans utilize VA health benefits.

- For some this means they are receiving care at a non-VA facility and for others it means they are not receiving care at all.

- Care at civilian facilities means healthcare professionals who may not have a full understanding of veteran issues (12).

- Less than 50% of veterans returning from deployment receive any mental health services (23).

All service members exiting the military are required to participate in the Transition Assistance Program (TAP), an information and training program designed to help veterans transition back to civilian life, either before leaving the military or retiring. The program is evaluated annually for effectiveness and currently includes components about skills and training for civilian jobs and individual counseling regarding plans after exit.

- Adding or strengthening components of TAP surrounding mental health care and utilization of VA healthcare services would be beneficial and could help reduce disparities.

- Changing the military culture surrounding mental health to strengthen and mandate training and usage of debriefing for active duty military could be beneficial as well.

- Incentivizing usage of the VA healthcare system for routine preventative and mental health care would help reach more veterans who may be in need.

Additional training for healthcare professionals working within the VA with an emphasis on cultural competence and mental health disorders would ensure high quality of care for veterans utilizing their services.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- The Transitional Assistance Program was established in 1991. In what ways do you think the experience of leaving or retiring from the military is different for veterans before and after this program was established?

- In what ways do you think that trauma is the catalyst for many of the other veteran specific issues they experience?

- How could trauma better be handled for these patients in order to reduce their risk of all the other related issues?

Mental Illness & Disability

Disabilities are emerging as an under-recognized risk factor for health disparities in recent years, and this new recognition is a welcome change as more than 18% of the U.S (15) population is considered disabled. Disabilities can be congenital or acquired and include conditions that people are born with (such as Down Syndrome, limb differences, blindness, deafness), those presenting in early childhood (Autism, language delays), mental health disorders (bipolar, schizophrenia), acquired injuries (spinal cord injuries, limb amputations, change in hearing/vision), and age related issues (dementia, mobility impairment).

Public health surveys vary from state to state, but most categorize a condition as a disability based on the following: 1) blindness or deafness in any capacity at any age, 2) serious difficulties with concentrating, remembering, and decision making, 3) difficulty walking or climbing stairs, 4) difficulty with self-care activities such as dressing or bathing, 5) and difficulty completing errands, such as going to an appointment, alone over the age of 15 (19).

Health disparities affecting people with disabilities can include the way they are recognized, their access and use of care, and their engagement in unhealthy behaviors. In order to practice cultural competence in nursing, understanding the disparities that those with disabilities face is essential.

- Due to variations in the way disabilities are assessed, the reported prevalence of disabilities ranges from 12% to 30% of the population (19).

- People with disabilities are less likely to receive needed preventative care and screenings (15).

- Only 78% of women with disabilities were up to date with their pap test, while over 82% of non-disabled women were up to date with this preventative screening (19).

- People with disabilities are at an increased risk of chronic health conditions and have poorer outcomes (15).

- 27% of people with disabilities did not see a doctor when needed, due to cost, as opposed to only 12% of non-disabled peers (19).

- 21% of children with disabilities were obese, compared to 15% of children without disabilities (19).

- People with disabilities are more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as cigarette smoking and lack of physical exercise than people without disabilities (15).

- During Hurricane Katrina, 38% of the people who did not evacuate were limited in their mobility or providing care to someone with a disability (19).

Much of the health differences between those with and without disabilities comes down to social factors like education, employment (finances), and transportation which significantly affect access to care.

- 13% of people with disabilities did not finish high school, compared to 9% of non-disabled peers.

- Only 17% of people over the age of 16 with disabilities were employed, compared to nearly 64% of non-disabled peers.

- Only 54% of people with disabilities had at-home access to the internet, compared to 85% of people without disabilities.

- 34% of people with disabilities reported both an annual income <$15,000 and access to transportation, compared to 15% and 16% respectively for people without disabilities.

- Fewer than 50% of people with disabilities have private insurance, while 75% of people without disabilities have private health insurance.

- Even for those insured, 16% of people with disabilities have forgone care due to cost, compared to only 5.8% of insured people without disabilities (19).

If access to necessary preventive and acute health care is to be increased for those with disabilities, much must be changed in regards to the social determinants affecting this population. Policy change on a community, state, and federal level will be needed to provide the social and economic support these people need. Potential solutions include:

- Streamline and standardize the process of identifying people with disabilities so they can be eligible for assistance as needed.

- School programs to help people with disabilities graduate and find jobs within their ability level.

- Community participation in making sure transportation, buildings, and facilities are accessible to all.

- Make internet access a basic and affordable utility, like running water and electricity.

- Address the inequities in health insurance accessibility and coverage.

- Provide social and economic support programs for parents of children with disabilities and provide transitional support as those children become adults (15).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for a patient with a serious disability? Consider the ways in which even getting to the clinic or hospital where you work might be different or more challenging than for patients without a disability.

- What resources for people with disabilities are available in the community where you live?

- How do you think those resources might vary in surrounding areas?

Conclusion

In short, cultural competence in nursing means that although a provider may not share the same beliefs, values, or experiences as their patients, they understand that in order to meet the patient’s needs, they must tailor their care delivery. Nurses are patient advocates, and it is on them to ensure that they are providing equitable and inclusive care to all populations.

However, cultural competence in nursing is ever changing and it is the responsibility of the provider to stay up-to-date in order to offer the best experience for all patients.

Connecticut Mental Health Conditions

Introduction

Mental health conditions are common in the United States, with one in five adults suffering symptoms ranging from mild to severe each year. Despite this fairly high prevalence, 2020 data indicates that only 46% of adults with a mental health condition received medical services related to those symptoms (10). Furthermore, experiencing one mental health disorder increases the risk of developing a second or third disorder by two to three fold (13). Comorbid mental health diagnoses also increase the severity of symptoms, negative impacts on quality of life, and risk of suicidal ideations (3)

Current practices surrounding mental health leave many people at risk of being undiagnosed or untreated and increased awareness and education is needed for medical professionals to help close these gaps in care. This Connecticut mental health training aims to provide a thorough understanding of certain common mental health disorders, how to screen for them and coordinate resources for clients in need, and how to navigate suicide prevention for optimum client safety.

Epidemiology

Every year, millions of people nationwide suffer from mental health related symptoms that impact their ability to work, attend school, maintain relationships, and enjoy their lives. Recent data indicates that one in five United States adults experiences symptoms of mental illness each year and one in twenty experiences severe symptoms (6). One in six United States children experiences mental illness symptoms each year and suicide is the second leading cause of death in the 10-14 year age group (6).

As of 2020, anxiety disorders were the most prevalent, with 19.1% of all US adults experiencing some form of anxiety annually. Depression is next, with a prevalence of 8.4%, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) experienced by 3.6%, and bipolar disorder experienced by 2.8% of adults (6).

There is mild variance among races, with annual prevalence among races outlined as follows:

- Non-Hispanic multiracial people: 35.8%

- Non-Hispanic white: 22.6%

- Non-Hispanic American Indian: 18.7%

- Hispanic or Latino 18.4%

- Non-Hispanic black: 17.3%

- Non-Hispanic Asian: 13.9%

(6)

Women are more likely to experience mental illness than men, with 25.8% of women 15.8% of men reporting symptoms annually (NIH). Being part of the LGBTQ community is one of the greatest risk factors, with 47.4% of LGBTQ people experiencing mental illness (6).

In addition to the factors that increase risk of mental health disorders, experiencing mental health issues also increases other health related risks. Suffering depression increases the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disorder by 40-50% over the rest of the population, depending on severity. Thirty-two percent of people with mental illness also experience substance abuse disorders, as compared to 10% of the general population (6). The rate of academic struggles and dropping out of school are 2-3 times higher for children and teens with mental health diagnoses, which in part contributes to the higher rates of unemployment (6.4% vs 5.1%) experienced by people with mental health disorders (6). On a more global scale, it is estimated over $1 trillion is lost in productivity due to depression and anxiety disorders each year (6).

On the severe end of mental health consequences is suicide, currently the 12th leading cause of death nationwide (12). Overall, there has been a slight decrease in suicide rates in recent years, declining from 14.2 per 100,000 people annually in 2000 to 13.5 per 100,000 people in 2020 (12). Still, suicide is a devastating problem with twice as many people dying by suicide as homicide in recent years. Risk varies by many demographic factors with men being about 4 times more likely to commit suicide than women across all ages. Among women, suicide rate is highest for those ages 45-64, at 7.9 people per 100,000. And among men, the rate is highest for those age 75 and older, at 40.5 per 100,000. By race, American Indians and White men are significantly more affected (12).

When looking at younger populations, the biggest risk factor seems to be sexuality and gender identity. Gay, Lesbian, and bisexual teens are 4 times more likely to attempt suicide than straight peers and transgender teens are 9 times more likely to attempt suicide than cis-gender peers. Each year, 45% of LBGTQ teens report experiencing serious thoughts of suicide at least once (6).

Despite these serious implications and high rates of prevalence, less than half of affected people receive appropriate, regular mental health services. These statistics are staggering. This is the reason of why the Connecticut Department of Public Health implemented the Connecticut mental health training CE requirement to improve mental health outcomes. Lack of proximity to resources, prescription problems, delayed or canceled appointments, and complications due to the pandemic or even just symptoms causing poor compliance all serve as barriers to appropriate treatment (6). Healthcare professionals are guaranteed to encounter patients with mental health needs no matter what area of healthcare they work in, and universal improvements in education and preparedness to deal with mental health concerns is desperately needed and can serve to improve outcomes for patients everywhere.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

Think about the population you serve…How often does your job involve assessing the mental health needs of your clients? Given the statistics above, do you think your attention to mental health is sufficient or needs to be increased?

-

If a client you encountered admitted that they were suffering from symptoms of depression or anxiety, what resources are available for you to connect them with? If you are unsure, how could you compile a list of resources?

Signs, Symptoms and Criteria for Common Mental Health Diagnoses

Unless you work specifically in mental health, you may only have a vague understanding of what exactly certain mental health diagnoses mean, how they are treated, or what symptoms your clients are dealing with. A more in depth understanding of how mental health problems present and diagnostic criteria is one of the first steps towards better detection and treatment for vulnerable clients. The Connecticut Department of Public Health added this CE requirement of Connecticut mental health training in order to better serve the patient population.

Depression

Known as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or Clinical Depression, this is one of the most common mental health disorders. While this disorder may stereotypically be known as being sad or down, the actual criteria for depression is much more detailed and nuanced (9). According to the Diagnostics and Statistics Manual for mental health (DSM-5), MDD is defined as experiencing at least five of the following symptoms for at least a two week time period and at least one of the symptoms must be one of the first two on the list:

- Sad, depressed, or even flat or detached mood most days, for the majority of the day

- Decreased or lack of interest or pleasure in any activities throughout the day

- Decrease in appetite or significant weight loss without trying to lose weight

- Slowed thought process and movement, noticeable by others

- Fatigue or low energy levels most days

- Feeling worthless or unnecessarily guilty most days

- Decreased ability to think, concentrate, or make decisions most days

- Recurrent thoughts of death, with or without a plan, or thoughts that things would be easier if one was dead (9)

The number, combination, and severity of symptoms will vary by individual. Typically symptoms are severe enough to interfere with a person’s ability to work, attend school, or maintain their relationships as well as they would like. People with depression may also experience excessive worries about their health or increased rates of general physical complaints like headache or abdominal pain. MDD may occur as a single episode, but often occurs in recurrent episodes, lasting for a few weeks to months and then resolving for a period of time before returning. Persistent symptoms lasting two years or more, though often less severe in intensity, is known as dysthymia. Depression can also occur from hormonal changes during or after pregnancy and is known as perinatal depression. Some individuals suffer from depressive symptoms only at certain times of year, typically in the dark and cold months of fall and winter in the northern hemisphere; this is known as seasonal depression (9).

It is important to separate depression from grief which is a response to loss with similar, often overlapping, but distinguishably different from depression symptoms. In grief, there is an identifiable loss, whereas depression can occur without any particular precipitating event (for “no reason”). Grief involves sad or hopeless feelings intermixed with feelings of joy or peace, whereas depression is persistently low mood. Being close to loved ones often offers comfort or healing in grief, but isolation and withdrawing are more common with depression. And with grief, thoughts of death may occur as a person desires to reunite with a deceased loved one, while in depression thoughts of death center around feeling worthless or hopeless and no longer wishing to live (4).

Risk factors for depression include personal or family history of any depressive disorder, certain medical conditions that negatively impact quality of life, or even medications taken for other conditions. Major life events or traumas, including death of a loved one, divorce, moving, job changes, birth of child, abuse, or traumatic events can all increase the risk of subsequent depression (9).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

How can you differentiate a bad day (or several) with many of the symptoms of depression, from a true diagnosis of MDD?

-

How might someone grieving the loss of a loved one present differently than someone with depression after the same loss?

Anxiety

All people experience worries or stress over things throughout their lives. But anxiety disorders extend beyond normal worries in their frequency and intensity, occurring often enough and at a severity level that interferes with a person’s ability to function at work, school, or in their relationships with others. There are several distinct disorders that fall under the umbrella of anxiety and the differences lie in the triggers and the expression of symptoms, but the criteria of excessive worry is a common theme across all anxiety disorders (8).

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a common form of anxiety that involves a general sense of dread of anxiousness, typically about anything and everything rather than specific events. People with GAD may feel restless, on edge, have difficulty concentrating, become tired easily, be irritable or have difficulty regulating their emotions, have difficulty sleeping, or have frequent general physical complaints like headaches or stomach aches (8).

Panic disorder involves more extreme physical symptoms of anxiety, known as panic attacks. Sudden, intense bursts of anxiety involving a racing heart, chest pain, shortness of breath, shaking, intense feelings of dread, or an intense desire to flee a situation are considered panic attacks. They may occur in relation to stressful events or for no reason at all. Anyone can experience a panic attack, but experiencing them frequently and being unable to function at work, school, or home because of them is considered panic disorder (8).

Social anxiety disorder is anxiety triggered by situations with people outside of one’s home. This can be people you know, like classmates or extended family, or strangers like cashiers or healthcare professionals. Symptoms include feeling judged or watched by others, racing heart, being unable to speak up or speak clearly to others, avoiding eye contact, or feeling very self conscious (8).

Phobias are anxiety related symptoms that center on a very specific trigger or event. People with phobias will do everything they can to avoid the trigger, including refusing to go to a certain place or leave home. Common phobias include agoraphobia (fear of leaving home), blood, heights, airplanes, vomit or vomiting, certain animals (such as snakes, spiders, or dogs), needles or injections, or separation from parents (for children) (8).

Risk factors for anxiety include exposure to traumatic events (especially early in life), drug or alcohol use, frequent exposure to a stressful environment (at job or school), and family history of anxiety disorders. Certain medications and stimulants like nicotine and caffeine can increase the symptoms of anxiety (8).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

Have you ever felt so nervous about something that you wanted to stay home or avoid the event altogether? How do you think it might affect your daily life if you felt that same level of anxiety every day?

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a type of mental health disorder that develops as a response to experiencing a particularly dangerous, scary, or shocking event. An extreme response of “fight-or-flight” during a high stress event is very normal, but many people recover quickly, within a few days to weeks, and do not experience continued distress after the event is over. For other people, the intense symptoms of fear or anxiety continue long after the danger has resolved (11).

Symptoms that occur in response to an identifiable event, last more than a month, and are interfering with a person’s ability to function at work, school, or in relationships are considered to have PTSD. Symptoms include:

- Re-experiencing the event such as through flashbacks or nightmares

- Avoidance symptoms such as staying away from certain people, places, objects, or even music that serves as a reminder of the event

- Arousal symptoms of feeling on edge, angry, tense, easily startled, or having difficulty sleeping

- Cognition and mood symptoms such as difficulty remembering details surrounding the event, negative outlook on the world or about self, feelings of guilt or blame, lack of interest in things

- Children may experience symptoms of regression such as bedwetting or daytime accidents when previously continent, being unable to speak, acting out the event with toys, increased clinginess or fear of separation from parents or caregivers (10)

Risk factors for PTSD include experiencing war (both as a member of the military or a civilian), physical or sexual assault/abuse, car accidents, natural disasters, seeing someone be seriously injured or die, history of mental illness or substance abuse, and having few to no support systems in place during times of stress (11).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

Have you ever cared for a client who lived through a traumatic event? How did they talk about the event?

-

What sort of feelings or emotions did they seem to experience while discussing their trauma?

Suicide

Suicide by definition is the death of an individual from self-injurious behaviors and the intent to die from those behaviors. Reckless behaviors resulting in unintentional death are not considered suicide because there was no intent to die. People who attempt or commit suicide often feel worthless, hopeless, or that their life is a burden to others and the only escape from their symptoms or guilt is to end their life (12). Warning signs that individuals may be planning or preparing for suicide include increase agitation and substance use, withdrawing from others, researching methods of suicide, stating they have thought about or have the ability to commit suicide, sleeping too much or not at all, giving away possessions or calling/writing letters to say goodbye to loved ones, or a sudden and extreme improvement in depression symptoms (usually from the resolve to commit suicide) (2).

A suicide attempt is any self-injurious behavior engaged in as an attempt to die but which ultimately is non-fatal. Suicide attempts can be actions which do not even result in injury, but if death was the individual’s intent, it is considered a suicide attempt. Suicidal ideations are any thoughts, considerations, or detail planning related to ending one’s own life (12).

The leading method of suicide in recent years is firearms, accounting for more than half of all suicides (11).

Risk factors for suicide include existing mental illness (especially depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia), substance abuse problems, terminal health diagnosis (particularly those that are very painful), persistent bullying or relationship problems, unemployment, highly stressful life events like divorce, family history of suicide or personal past attempts, and childhood trauma or neglect. Having access to guns, knives, pills, or other potentially lethal materials increases the risk of suicide as well (2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for a client who was contemplating suicide? What life events had occurred leading up to these thoughts?

Case Study

Jason is a 78 year old male who presents at the Internal Medicine office for his annual physical. When the nurse is collecting vitals, she chats with him about his plans for the summer. He states that he and his late wife used to garden together and he has kept up with it for the last 3 years since her death but this year he does not feel up to planning it or doing the work. The nurse asks if he has other plans for how to occupy his time and he states he usually has a group of friends he gets coffee with twice a week, but he hasn’t been waking up early enough to go to it and has decided to sleep in instead. The nurse documents his vitals and reports off to the physician, attributing his “slowing down” to his advancing age. During the visit, his doctor asks how he is coping with his wife’s loss to which Jason replies, “I’m okay. It never gets easier, but you do get used to it.” The physician orders labs to check his iron levels for fatigue and provides a pamphlet for a support group for widows and widowers at the end of the visit. He recommends Jason follow up in another 3-4 months if his fatigue hasn’t improved.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

Do you feel confident that the nurse and the physician have a thorough understanding of Jason’s mental health at the end of this visit?

-

What are Jason’s risk factors for mental health diagnoses? What symptoms of depression is he experiencing?

-

How might grief resources fall short of addressing Jason’s symptoms?

Screening

Regardless of which area of healthcare you work in, there will always be clients who are struggling with mental health symptoms, even if that is not their primary reason for seeking care at your facility. Routine and standardized screening for these symptoms can help ensure more clients who need help are identified and prevent many from falling through the cracks. Earlier detection of symptoms ultimately leads to better mental health outcomes as well, so simple and routine screenings serve to improve identification and distribution of care to those in need. Improving mental health outcomes is the primary goal of Connecticut implementing this CE requirement of Connecticut mental health training. So who should undergo screening, when should the screenings occur, and what are some of the best or most common screening tools available?

Let’s start with children since over 50% of all lifetime mental health disorders first appear by age 14.. At every wellness visit, it is recommended to ask general questions about family psychosocial wellness such as childcare resources, availability of food, parent coping with the stressors of parenthood, and normal psychosocial development in the child such as language, eye contact, bonding with family members, play, and age appropriate response to praise and consequences. Families where problems are suspected should be evaluated further. Starting at age 11, the use of more streamlined screening tools is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and/or Pediatric Symptoms Checklist (PSC) should be used annually to detect increased risk of depression, anxiety, or suicidal thoughts. The CRAFFT questionnaire is recommended annually for screening of substance use, starting at age 11. For children who seem anxious or where excessive worries or behavior problems are a concern, a SCARED questionnaire can assess more specifically for anxiety disorders (1).

Once into adulthood, the PHQ-9 is still a reliable and easy to use tool and should be administered at all annual wellness visits. The General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) tool is also quick to administer and can pick up on clients who may be experiencing excessive worries (5). In more acute settings like urgent cares or emergency departments, a simple screening question such as “Do you feel safe at home?” can determine situations that may need acute interventions for clients who may not be receiving regular primary care.

In addition to annual screening, healthcare providers should be aware of life events that may increase a person’s risk of experiencing a mental health disorder and perform additional screening as needed. In obstetrics and gynecology settings, women should be screened throughout pregnancy and postpartum for perinatal mood disorders using an Edinburg Questionnaire. Pediatric offices can also screen mothers of infant clients since women often see their child’s pediatrician much more frequently than their own obstetrician or midwife (5). Older adults are more likely to be experiencing declining health, chronic medical diagnoses, or life events such as retirement or the loss of a spouse that increase their risk of depression or anxiety. Assuming their age alone is the cause of certain symptoms should be avoided, while energy and activity levels may indeed decline in later life, a lack of interest or pleasure in things or feelings of hopelessness are not normal signs of aging and should not be brushed off. Updated information on recent life events is important and increased screening should be done accordingly. War veterans, disaster or abuse survivors, and others may find themselves seeking care for physical symptoms related to trauma, but their mental health should be considered and assessed immediately after the event as well as regularly for several months afterwards (5).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

Think about the population you work with. What factors (age, life stage, general health) put them most at risk for mental health symptoms?

-

What screening questionnaires, if any, do you routinely use at your facility? What additional screening tools could you use to improve your detection rates?

Taking Action

The next step in closing the gap for early detection of mental health disorders is knowing what to do when clients screen positive or when they come to you specifically with a mental health concern or symptoms. A primary goal of the Connecticut mental health training is to prepare nurses with the knowledge and resources needed to get paitents on the right plan of care. Many facilities are surprised once they begin screening, just how many clients present with positive results or the need for further help.

The first thing to do is gather more information directly from the client. Ask about symptoms they have been feeling, how long it has been going on, recent life events that may be contributing to these feelings, and ways in which the symptoms have been impacting their performance at work, in school, or in other aspects of life. Gather a family history that focuses specifically on mental health disorders to better assess disorders for which a client is at risk. Determine the client’s overall safety; the best way to do this is to ask directly if they are having thoughts of wanting to harm themselves or others. This will help determine if intervention is needed urgently or if a more routine connection with resources is appropriate (2).

Once more thorough information has been gathered about a client’s particular scenario, providers can determine the best course of action and what resources to connect them with. It is useful for facilities to have a list of resources available. Appropriate resources include providers who can diagnose and prescribe treatment for mental health disorders (this can often be done in primary care settings, but specialists like psychiatry may be more appropriate), therapists or counselors, group therapies or support groups with common themes, and crisis resources like suicide hotlines or facilities that can be accessed 24/7 in the event of a crisis. When connecting clients with resources, plan for appropriate follow up as well to ensure they received the help they needed (2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

-

What resources are available in your area for routine therapy or counseling? Are there any support groups that you know of for grief or loss, LGBTQ people, or veterans?

-

How do you think it might make a client feel if they admitted to struggling with depression or anxiety and were not given any resources or next steps at the end of their experience at your facility?

-

What are the risks involved with not appropriately addressing their symptoms at the time of care?

Suicide Prevention

On a broad scale, healthcare professionals can participate in suicide prevention by advocating for screening and early detection of mental illness, as well as identifying risk factors and protective factors for their clients to determine who may need connection with available resources. On a community health level, strengthening available resources and the community’s access to them can promote social change needed for prevention (7).

On a more individual level, familiarity with what to do when encountering suicidal clients is always useful, though the actually frequency at which you encounter such clients may vary greatly depending on where you work. If you have concerns or a client fails a screening tool, it is always okay to ask them outright if they have thoughts of wanting to hurt themselves. It is a myth that asking someone this will give them the idea and no studies indicate asking this would contribute to suicide risk. If a client indicates they are having thoughts of suicide or self harm, the next steps should be to determine how often these thoughts are occurring and if they have a plan. It can feel awkward to ask these types of questions, but it is extremely important for client safety and studies indicate that most people would like the help and support extended to them. If they admit to having a plan, the next step is to determine if they have the means to enact the plan. If they say they want to take a lethal dose of pills, determine what medicines they have available to them; if they say they have thought about using a firearm, determine if firearms and ammunition are accessible to them (7).

Clients with an active plan and the means to enact said plan will need crisis intervention and likely involuntary hospital admission. Anyone with thoughts of suicide, even passive ones with no plan, will require further evaluation with a counselor or provider experienced in mental health. Specific plans moving forward for these clients is beyond the scope of this course, but often involve the development of Safety Plans, initiation of psychiatric medication, and connection with resources such as individual or group therapists. The important thing for healthcare professionals in general is to be able to determine when clients are a risk to themselves or others and ensure they are connected with resources before leaving your care (7). This is what the Connecticut Department of Public Health wants to educate nurses on and is why they implemented a CE requirement of the Connecticut mental health training.

Revisit Case Study

Let’s take a look at Jason’s case again and consider how things might have gone differently with better mental health protocols for the facility.

Jason is a 78 year old male who presents at the Internal Medicine office for his annual physical. When the nurse is collecting vitals, she chats with him about his plans for the summer. He states that he and his late wife used to garden together and he has kept up with it for the last 3 years since her death but this year he does not feel up to planning it or doing the work. The nurse asks if he has other plans for how to occupy his time and he states he usually has a group of friends he gets coffee with twice a week, but he hasn’t been waking up early enough to go to it and has decided to sleep in instead. The nurse notes the PHQ-9 questionnaire Jason completed at check in and sees the score is 20/27, which is indicative of depression.

The nurse documents his vitals and reports off to the physician, mentioning Jason’s PHQ score and his lack of interest in his usual activities. During the visit, his doctor asks how he has been feeling lately and if he has been sad or lonely. Jason discloses that he has been feeling down lately and not wanting to do the usual things that he enjoys. His doctor asks if he has any thoughts of suicide or wanting to hurt himself which Jason denies. After a thorough assessment, Jason is diagnosed with MDD and given a trial of fluoxetine. His doctor also recommends Jason establish with a therapist. Follow up is scheduled in 3 weeks to check in on how the new medication is going.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What improvements do you note in the way this scenario played out?

- How is depression differentiated from grief in this scenario? In what ways is the management of depression different from that of grief?

- Why is close follow-up beneficial in this scenario?

Alzheimers Nursing Care

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is a destructive, progressive, and irreversible brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking. Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia in older adults (1). For most people who have Alzheimer’s disease, symptoms first appear in their mid 60’s (1).

Studies suggest more than 5.5 million Americans, most 65 or older, may have dementia caused by Alzheimer’s (1). It is currently listed as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States. It is essential to understand the signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s dementia and how to manage the care of a patient, family member, or friend suffering from the disease.

Dementia is the loss of cognitive functioning, such as thinking, remembering, reasoning, and behavioral abilities, such as a decreased ability to perform activities of daily living (1). The severity of dementia ranges from mild to severe. Dmentia’s mildest stage often begins with forgetfulness, while its most severe stage consists of complete dependence on others for general activities of daily living (1).

History of Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s disease is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer. In the early 1900s, Dr. Alzheimer noticed changes in the brain tissue of a patient who had died of an unknown mental illness. The patient’s symptoms included memory loss, language problems, and unpredictable behavior.

After her death, her brain was examined and was noted to have abnormal clumps known as amyloid plaques and tangled bundled fibers, known as neurofibrillary or tau tangles (1). These plaques and tangles within the brain are considered some of the main features of Alzheimer’s disease. Another feature includes connections of neurons in the brain. Neurons are a type of nerve cell responsible for sending messages between different parts of the brain and from the brain to other parts of the body (1).

Scientists are continuing to study the complex brain changes involved with the disease of Alzheimer’s. The changes in the brain could begin ten years or more before cognitive problems start to surface.

During this stage of the disease, people affected seem to be symptom-free; however, toxin changes occur within the brain (1). Initial damage in the brain occurs within the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, which are the parts of the brain that are necessary for memory formation. As the disease progresses, additional aspects of the brain become affected, and overall brain tissue shrinks significantly (1).

Signs and Symptoms & Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease

Memory problems are typically among the first signs of cognitive impairment related to Alzheimer’s disease. Some people with memory problems have Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) (2). In this condition, people have more memory problems than usual for their age; however, their symptoms do not interfere with their daily lives.

Older people with MCI are at increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. The first symptoms of Alzheimer’s may vary from person to person. Many people display a decline in non-memory-related aspects of cognition, such as word-finding, visual issues, impaired judgment, or reasoning (2).

Healthcare providers use several methods and tools to determine the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Dementia. Diagnosis and evaluation involve memory, problem-solving, attention, counting, and language tests. Healthcare providers may perform brain scans, including CVT. MRI or PET is used to rule out other causes of symptoms.

Various tests may be repeated to give doctors information about how memory and cognitive functions change over time. They can help diagnose different causes of memory problems, such as stroke, tumors, Parkinson’s disease, and vascular dementia. Alzheimer’s disease can be diagnosed only after death by linking clinical measures with an examination of brain tissue in an autopsy (3).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you experienced a patient in your practice with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease? What did their symptoms look like?

- What standard diagnostic tools do healthcare providers use to diagnose this disease?

- What is the definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease?

Stages of Disease

Mild Alzheimer’s

People experience significant memory loss and other cognitive problems as the disease progresses. Most people are diagnosed in this stage (1).

- Wandering/getting lost

- Trouble handling money or paying bills

- Repeating questions

- Taking longer to complete basic daily tasks

- Personality/behavioral changes (1)

Moderate Alzheimer’s

In this stage, damage occurs in the area of the brain that controls language, reasoning, sensory processing, and conscious thought (1).

- Memory and confusion worsen.

- Problems recognizing family and friends

- Unable to learn new things

- Trouble with multi-step tasks such as getting dressed

- Trouble coping with situations

- Hallucinations/delusions/paranoia (1)

Severe Alzheimer’s

- Plaques and tangles spread throughout the brain, and brain tissue shrinks significantly.

- Cannot communicate

- Entirely dependent on others for care

- Bedridden – most often as the body shuts down

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some of the signs and symptoms that differentiate each stage of Alzheimer’s disease?

- A person is in what stage of Alzheimer’s disease when they struggle to recognize family members and friends?

Prevention

Many aging patients worry about developing Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Especially if they have had a family member who suffered from the disease, patients may worry about genetic risk. Although there have been many ongoing studies on the prevention of the disease, nothing has been proven to prevent or delay dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease (2).

More research suggests that women are more likely to develop dementia and Alzheimer’s compared to men. Further research is needed to determine the role between genetics, sex, and Alzheimer’s risk (4).

A review led by experts from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found encouraging yet inconclusive evidence for three types of interventions related to ways to prevent or delay Alzheimer’s Dementia or age-related cognitive decline (2):

- Increased physical activity

- Blood pressure control

- Cognitive training

Treatment of the Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is complex and is continuously being studied. Current treatment approaches focus on helping people maintain their mental function, manage behavioral symptoms, and lower the severity of symptoms. The FDA has approved several prescription drugs to treat those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s (3).

Treating symptoms of Alzheimer’s can provide patients with comfort, dignity, and independence for a more significant amount of time while simultaneously assisting their caregivers. The approved medications are most beneficial in the early or middle stages of the disease (3).

Cholinesterase inhibitors are prescribed for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease; they may help to reduce symptoms. Medications include Rzadyne®, Exelon®, and Aricept® (3). Scientists do not fully understand how cholinesterase inhibitors work to treat the disease; however, research indicates that they prevent acetylcholine breakdown. Acetylcholine is a brain chemical believed to help memory and thinking (3).

For those suffering from moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease, a medication known as Namenda®, which is an N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, can be prescribed. This drug helps to decrease symptoms, allowing some people to maintain certain essential daily functions slightly longer than they would without medication (3).

For example, this medication could help a person in the later stage of the disease maintain their ability to use the bathroom independently for several more months, benefiting the patient and the caregiver (3). This drug works by regulating glutamate, an essential chemical in the brain. When it is produced in large amounts, glutamate may lead to brain cell death. Because NMDA antagonists work differently from cholinesterase inhibitors, these rugs can be prescribed in combination (3).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Is there a cure for this disease?

- What are some of the treatment forms that have been used for the management of Alzheimer’s disease?

- Can medications be used in conjunction with one another to treat the disease?

Medications to be Used with Caution in those Diagnosed with Alzheimer’s

Some medications, such as sleep aids, anxiety medications, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics, should only be taken by a patient diagnosed with Alzheimer’s after the prescriber has explained the risks and side effects of the medications (3).

Sleep aids: They help people get to sleep and stay asleep. People with Alzheimer’s should not take these drugs regularly because they could make the person more confused and at a higher risk for falls.

Anti-anxiety: These treat agitation and can cause sleepiness, dizziness, falls, and confusion (3).

Anticonvulsants: These are used to treat severe aggression and have possible side effects of mood changes, confusion, drowsiness, and loss of balance.

Antipsychotics: they are used to treat paranoia, hallucinations, agitation, and aggression. Side effects can include the risk of death in older people with dementia. They would only be given when the provider agrees the symptoms are severe enough to justify the risk (3).

Caregiving

Coping with Agitation and Aggression

People with Alzheimer’s disease may become agitated or aggressive as the disease progresses. Agitation causes restlessness and causes someone to be unable to settle down. It may also cause pacing, sleeplessness, or aggression (5). As a caregiver, it is essential to remember that agitation and aggression are usually happening for reasons such as pain, depression, stress, lack of sleep, constipation, soiled underwear, a sudden change in routine, loneliness, and the interaction of medications (5). Look for the signs of aggression and agitation. It is helpful to prevent problems before they happen.

Ways to cope with agitation and aggression (5):

- Reassure the person. Speak calmly. Listen to concerns and frustrations.

- Allow the person to keep as much control as possible.