Course

Kidney Transplant: Procedure and Aftercare

Course Highlights

- In this Kidney Transplant: Procedure and Aftercare course, we will learn about the kidney transplant process.

- You’ll also learn how to identify complications of a kidney transplant.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the common causes of ESKD.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 3

Course By:

Michael York

MSN, RN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

End-stage kidney disease profoundly impacts the lives of thousands of Americans, imposing physical, emotional, and social limitations. The journey towards a kidney transplant is intricate and often lengthy. In this course, we will delve into the complexities of the kidney transplant process, exploring the kidney function, indications for a kidney transplant, and the aspects of the procedure.

Kidney Transplant

Kidney transplant is the best choice of treatment for people with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) to ensure survival and a good quality of life. A kidney transplant can come from either a living or deceased donor.

The transplanted kidney or allograft is surgically placed into the recipient’s lower abdomen. The allograft’s renal artery and vein are anastomosed to the recipient’s vasculature and the allograft’s ureter is anastomosed to the recipient’s ureter (5, 8, 18).

The United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) is the organization that oversees all types of solid organ transplants within the United States. They are the governing body that sets the basic criteria for both recipients and donors. UNOS controls the waitlist for all transplant candidates.

This organization keeps data on everything related to transplants and revealed the following:

- In 2021, there were 24,670 kidney transplants.

- In 2022, there were 25,500 kidney transplants.

- From 2023 to date, there have been 24,975 kidney transplants.

(7)

Each transplant center is responsible for assessing and placing kidney transplant candidates on the UNOS kidney transplant waitlist. Once on the waitlist, candidates must be reassessed periodically to ensure that they remain good candidates for transplant. The wait time to receive a deceased donor kidney varies depending on the location of the transplant center.

The overall average wait time is approximately four years. However, by center location, average wait times can be as low as four months or longer than six years.

The other factors that determine how long a candidate may wait before a kidney becomes available include:

- Length of time on dialysis. The longer someone has been on dialysis, the more kidney offers they may receive.

- Blood type. Common blood types will generally receive a kidney faster than others.

- Age.

- Antigens and antibodies. Possessing certain antigens or antibodies in the blood may make it difficult to find a compatible kidney. Blood transfusions, pregnancies and previous transplants may increase these antigens and antibodies.

- Where a candidate lives. The deceased-donor kidney process of allocation is somewhat based on proximity to the deceased donor.

An unfortunate truth is that there is a shortage of donors and many kidney transplant candidates, approximately 5%, die on the waitlist. Currently, approximately 93,000 people are waiting on the UNOS kidney transplant waitlist (22).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is another name for a transplanted kidney?

- What are two types of kidney transplants?

- Name two factors that can affect kidney transplant wait times.

- Approximately how many people are on the kidney transplant waitlist?

Kidney Transplant

Kidney transplant is the best choice of treatment for people with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) to ensure survival and a good quality of life. A kidney transplant can come from either a living or deceased donor.

The transplanted kidney or allograft is surgically placed into the recipient’s lower abdomen. The allograft’s renal artery and vein are anastomosed to the recipient’s vasculature and the allograft’s ureter is anastomosed to the recipient’s ureter (5, 8, 18).

The United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) is the organization that oversees all types of solid organ transplants within the United States. They are the governing body that sets the basic criteria for both recipients and donors. UNOS controls the waitlist for all transplant candidates.

This organization keeps data on everything related to transplants and revealed the following:

- In 2021, there were 24,670 kidney transplants.

- In 2022, there were 25,500 kidney transplants.

- From 2023 to date, there have been 24,975 kidney transplants.

(7)

Each transplant center is responsible for assessing and placing kidney transplant candidates on the UNOS kidney transplant waitlist. Once on the waitlist, candidates must be reassessed periodically to ensure that they remain good candidates for transplant. The wait time to receive a deceased donor kidney varies depending on the location of the transplant center.

The overall average wait time is approximately four years. However, by center location, average wait times can be as low as four months or longer than six years.

The other factors that determine how long a candidate may wait before a kidney becomes available include:

- Length of time on dialysis. The longer someone has been on dialysis, the more kidney offers they may receive.

- Blood type. Common blood types will generally receive a kidney faster than others.

- Age.

- Antigens and antibodies. Possessing certain antigens or antibodies in the blood may make it difficult to find a compatible kidney. Blood transfusions, pregnancies and previous transplants may increase these antigens and antibodies.

- Where a candidate lives. The deceased-donor kidney process of allocation is somewhat based on proximity to the deceased donor.

An unfortunate truth is that there is a shortage of donors and many kidney transplant candidates, approximately 5%, die on the waitlist. Currently, approximately 93,000 people are waiting on the UNOS kidney transplant waitlist (22).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is the function of the kidneys?

- What are the two sections of the kidney?

- What is the functional segment of the kidney?

- What is the removed waste called?

- Which vessel supplies the kidney with blood?

Kidney Diseases and Disorders

Various diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and autoimmune disorders, can significantly impact the health and function of the kidneys. This section will examine diseases and disorders that impact the function of the kidneys and can ultimately lead to the need for a transplant.

Diabetes

Worldwide, diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common cause of ESKD. Approximately 40% of patients with ESKD due to DM will require some sort of renal replacement therapy. Just as DM is a progressive disease, diabetic nephropathy is also progressive.

Initially, albuminuria will develop. This is where albumin is present in the urine. Microalbuminuria is usually the first abnormality that occurs in patients with diabetic nephropathy. This can progress to macroalbuminuria.

Macroalbuminuria leads to a decline in the GFR as the large proteins damage the glomeruli. Albuminuria remains a diagnostic tool for diabetic nephropathy and a prognostic tool for ESKD (17).

Focal Segmental Glomerulonephritis (FSGS)

FSGS is known to be one of the most common glomerular causes of ESKD. It is the most prevalent glomerulopathy diagnosed by biopsy throughout the world today. More than 50% of patients develop ESKD within ten years of being diagnosed. FSGS can affect people of any age.

It is most common in males and is approximately five times higher in African American patients as compared to Caucasians. The most common site for FSGS lesions is the podocyte. Podocytes are the cells that maintain the integrity of the glomeruli. With primary FSGS, the podocyte damage is rapid and global within the cells.

In secondary FSGS, the injury is slow and demonstrates podocyte foot effacement in approximately 80% of the capillary surface. As the podocytes are destroyed, the remaining podocytes hypertrophy to cover the capillary surface. Intercapillary hypertension ensues, further damaging the cells which leads to sclerosis (20).

Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD)

PKD causes an irreversible and progressive decline in kidney function which will lead to kidney failure. It is known for its development of fluid-filled cysts which take over the functioning of kidney tissue. The cysts can become so numerous that they overcome the kidney entirely. They may also cause the kidneys to appear extremely large.

Patients with PKD may also present with liver cysts and brain aneurysms. When being screened for a kidney transplant, liver and brain imaging should be considered to rule out any issues. This is a genetic disease (12).

Lupus Nephritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease that can affect virtually all systems within the body. It is most common among women of child-bearing age and often has kidney involvement. Lupus nephritis is common in patients with SLE and affects greater than 50% of SLE patients.

It is the main cause of kidney injury within the SLE patient population. SLE is more aggressive in male patients, and they tend to have a higher incidence of lupus nephritis. Lupus nephritis may lead to kidney failure, requiring dialysis and/or kidney transplant (16).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Name two diseases that can lead to ESKD.

- How is PKD characterized?

- What is the most common site for FSGS lesions?

- In PKD, where else may cysts develop?

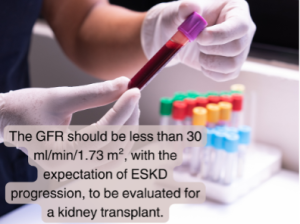

Clinical Indications for Transplant

To be evaluated for a kidney transplant, the GFR should be less than 30 ml/min/1.73 m² with the expectation of progressing to ESKD. However, a potential transplant candidate cannot be added to the UNOS kidney transplant waitlist until the GFR is less than 20 ml/min/1.73 m².

Active malignancy, and in some cases, a history of malignancy will make a potential transplant candidate ineligible for a kidney transplant. Frailty and severe or serious disease processes may also lead a transplant clinic to deny a candidate (5).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What must the GFR be to be evaluated for a kidney transplant?

- What must the GFR be to list the patient on the UNOS kidney transplant waitlist?

- What might make a patient ineligible for a kidney transplant?

- What is the progression from diabetic nephropathy to ESKD?

Waiting List Process

Patients can be referred to a transplant center by a physician, their dialysis center, or they can self-refer. The first visit to the transplant center will take a long time, up to four hours. They will meet separately with the entire transplant team: the transplant coordinator, the transplant nephrologist, the transplant surgeon, the social worker, the dietitian, and the financial coordinator. Each discipline assesses the potential candidate from a different point of view.

They all have specific criteria to determine if the patient will be a good candidate for a kidney transplant or not. If, at the end of the initial appointment, the team deems that the patient is a good candidate for transplant, the physician will order some pretransplant testing that must be completed and reviewed before placing the patient on the UNOS kidney transplant waitlist. The pretransplant work-up will include imaging such as a chest x-ray and abdominal CT.

Multiple vials of blood will be drawn to obtain baseline labs. Blood typing will be drawn and then redrawn for confirmation. Blood type compatibility is the first hurdle in receiving a kidney transplant. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing will also be performed to determine compatibility with potential and actual donors. Cardiac work-up will also be done to assess cardiac function. The type of cardiac testing will be determined by age, diabetic status, and whether the patient is on dialysis or not.

The patient will be assessed for malignancy. A PSA test for men and, depending on age, a mammogram for women. Should either test come back abnormal, further testing such as imaging or biopsy may be required. Also, any abnormal skin lesions noted during the initial appointment will have to be assessed by a skin specialist. A colonoscopy will also be ordered to rule out any gastrointestinal malignancy.

The patient’s social support system is also assessed. The patient must have good support from family and/or friends to be considered for transplant. The immediate post-hospital stay can be very strenuous, and the patient will need someone to stay with them and take them to the multiple appointments that are required in the first few months.

Also, the patient’s financial status is considered. The patient must be able to meet their transplant-related financial obligations. The inability to obtain medication due to financial status would put the allograft and possibly the patient’s life in jeopardy.

Once all the testing has been completed and the results have been assessed by the transplant nephrologist/surgeon, the candidate’s case will be brought before the selection committee. The selection committee consists of the transplant team; the same members who assessed the patient on their initial visit. Again, each member will have an opportunity to speak about whether the patient is a good candidate or not.

This is a truly multidisciplinary approach where each discipline has an equal voice. The committee is not just assessing medical status, but also social support, financial resources, and ability to adhere to complex regimens (5, 18).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Name two disciplines involved in the multidisciplinary team.

- What are two tests that may be included in the pre-transplant work-up?

- Why would the patient’s social support system be assessed?

- Who decides if a patient will be listed on the UNOS kidney transplant waitlist?

- Whose voice carries the most weight on the Selection Committee?

Donor Selection

Though the basic selection criteria for living donor acceptance is established by UNOS, each transplant center can modify the criteria (as long as the minimum criteria are met) to their needs. Many factors are considered when selecting a living donor.

As this is an elective surgery that has no physical benefit to the donor, the selection process may be more strenuous than the selection process to list a transplant recipient candidate. Potential living kidney donors must be in exceptional health with low predictors of possible kidney disease in the future, especially with the added risk of having only one kidney.

Kidney donors, whether living or deceased, must be blood type compatible and HLA compatible with the recipient.

Age

Age is a key factor in kidney donor selection. Though a kidney from a younger person tends to have a better allograft outcome, donors who are greater than 60 years of age may still be considered for kidney donation.

The pros and cons must be weighed heavily considering the risk of surgery on the potential donor. The risk of leaving the potential recipient on the waitlist; waiting for a viable organ. Many patients on the waitlist die every year, never having received a kidney transplant.

Hypertension

As hypertension is a leading cause of kidney failure, a potential donor’s blood pressure status. “White coat syndrome” happens to many patients when they visit a clinic or doctor’s office. This is when blood pressure is increased due to the stress of being in the doctor’s office.

When a potential donor presents with increased blood pressure, the blood pressure should be monitored over a week. Even if the blood pressure remains high, this may not preclude donation. If the patient is otherwise healthy and if the patient is on no more than two antihypertensive medications, they may be considered for donation.

Diabetes

Most transplant centers in the United States have deemed both type 1 and type 2 diabetes as an absolute contraindication to live kidney donation. Prediabetic patients have been considered as potential donors. However, a robust evaluation must take place where all future scenarios are considered. Diabetes is a known cause of both hypertension and kidney failure.

Obesity

Though obesity is not an absolute contraindication for living kidney donation, all guidelines have agreed that potential donors with a body mass index (BMI) of greater than 35 kg/m² must be excluded. Many individual transplant centers would like donors to have a BMI of less than 30 kg/m² to donate. Obese patients tend to heal slower and have an increased risk for postsurgical complications such as infection and non-healing wounds.

Obese patients are also at higher risk of developing health issues such as diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease (6). For a deceased donor kidney transplant, the criteria are a little different. UNOS has a minimum set of donor criteria that a transplant center can select when setting up their deceased donor program. The center can modify the criteria to suit their needs and patient population.

The allocation process for a deceased donor kidney transplant takes a lot of things into consideration and was created to ensure a fair process across the board. In 2017, a new allocation policy was created and was put into practice in December 2020.

When someone dies and is an organ donor, there is a 250-nautical-mile radius from the donor hospital to where the kidney will be offered. This circle is called the “local allocation” and typically, the transplant center within the circle will be offered the kidney first. This is to reduce the cold ischemic time and give the allograft the best possible chance for long-term survival. If there is no recipient identified within the 250 nautical mile radius, the offer will then go to centers outside the local allocation area (1).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why is the living donor evaluation so strenuous?

- Are people with high blood pressure able to become live donors?

- Why are obese people generally not good candidates to be a live donor?

- What is the “local allocation” area?

- Which disease process is an absolute contraindication to becoming a live donor?

Pre-Procedure

While the patient is on the kidney transplant waitlist, their health must be maintained so that they are ready for transplantation at any time. If on dialysis, the dialysis center will play a key part in both health maintenance and reporting any issues to the transplant center. They will return to the transplant center for a reassessment yearly as a minimum.

This is imperative to be sure that the candidate is ready now and stays ready for the call that a kidney is available. When a deceased donor kidney offer comes in and is a suitable match for the candidate, the transplant coordinator will coordinate the arrival of both the allograft and the patient to the hospital. Once the patient arrives, they will again undergo blood work to make sure that they are fit for transplant.

Any new symptoms of disease processes will have to be assessed and, depending on the disease and severity, the transplant may or may not take place. If they show any signs of infection, the procedure will be canceled (5, 18).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- When should a patient on the waitlist be ready for a kidney transplant?

- Once listed, how often are patients reevaluated at the transplant center?

- Which disease process is an absolute contraindication to becoming a live donor?

Procedure

The timing of the transplant surgery depends on the type of donor. For the deceased donor kidney transplant, the recipient must always be ready as the timing of the transplant is unknown. The wait is for someone compatible to pass away. Once a kidney has been matched to the recipient and the procurement surgery time has been set, the transplant center will call the recipient to the hospital and prepare them for transplant.

They will not go to the surgical suite until close to the estimated arrival time of the donor kidney. Typically, anesthesia will not be initiated until the kidney has arrived and has been evaluated by the transplant surgeon. The induction immunosuppressive agent will usually be given at the initiation of anesthesia.

For the living donor kidney transplant, the team has much more control of all the logistics. Both the procurement operation and the transplant surgery will be scheduled. First, the procurement will begin and once the kidney is about to be removed, the recipient’s anesthesia will be started, and they will be prepared for surgery in the surgical suite. The kidney will then be walked from one suite to the other and transplanted into the recipient.

In both cases, the surgeon will prepare the transplanted kidney on the back table in the surgical suite. Here they will identify the vein, artery, and ureter. They will also clean the kidney by removing any excess tissue and fat.

Open kidney transplant surgery is performed using either a pararectal incision or an oblique muscle-cutting incision. Whichever technique is used, the initial incision is approximately fifteen to twenty centimeters, either parallel to the inguinal ligament or down the lateral margin of the rectus abdominis muscle. Once a suitable landing has been identified, the surgeon will clamp the native artery and vein.

They will perform ureteral anastomoses and vascular anastomoses. When ready, the vasculature will be unclamped, and the allograft will be reperfused. From the time the allograft is clamped until the time it is unclamped is called cold ischemic time (8).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- When will a deceased donor kidney transplant take place?

- When is the induction immunosuppressant administered?

- How does the surgeon prepare the allograft on the back table?

- For live donation, why are the donor and recipient surgery staggered; and what is the cold ischemic time?

Aftercare

A kidney transplant is unlike any other type of surgery. The real management of the patient occurs after the surgery itself has been completed. Great measures are taken to ensure that the allograft survives and functions for as long as possible.

During the hospital stay, the patient is started on ten to fifteen new medications. These medications are to prevent rejection of the allograft, control blood pressure, prevent acid reflux, maintain magnesium levels, and prevent all types of infections; viral, bacterial, and fungal. Once the patient has been discharged, they will return to the transplant clinic frequently.

For the first four to six weeks, they will come in twice a week, then weekly for four to six weeks, then every other week, then monthly through the end of the first year. After the first year is complete, care of the patient may be transferred back to the patient’s nephrologist with yearly visits to the transplant center.

The patient will undergo lab work at every appointment. This is done to check kidney function, immunosuppressant levels, and overall wellness of the patient (18).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How often will the patient be seen at the transplant clinic post-transplant?

- How many new medications can the patient be expected to start post-transplant?

- When may the care of the patient be turned back over to their primary nephrologist?

- How often will labs be drawn?

Complications:

After the transplant, many complications can endanger both the allograft and patient survival. Any of these complications must be identified early and treated as quickly as possible to decrease the possibility of any long-term effects on the allograft.

Delayed Graft Function

Delayed graft function (DGF) is defined as an acute kidney injury requiring dialysis within the first week after transplant. On average, the incidence of DGF is about 31%. Acute rejection and shorter graft survival are associated with DGF.

Once DGF has been identified, the transplant physicians will often change the maintenance immunosuppressive therapy medications. Although there is no way to predict whether a transplanted kidney will undergo DGF, there are criteria that have shown a higher incidence of DGF. Prolonged cold ischemic time is linked with DGF (11).

Infection

Before transplant, patients are assessed for any signs of infection. As the patient will receive both induction and maintenance immunosuppressive therapy, any infection can become life-threatening. Two viral infections can have devastating effects on the kidney transplant patient: cytomegalovirus (CMV) and BK polyomavirus (BKV).

As part of the pretransplant work-up, patients are tested for both viruses. Patients are also tested for these viruses multiple times posttransplant, especially if there are any symptoms or drastic changes in lab values.

CMV is the most critical infection that can happen after a kidney transplant. Symptoms of CMV disease are fever, leucopenia, and enterocolitis. It is directly associated with high morbidity and mortality among kidney transplant patients. CMV is known to cause both acute and chronic graft injury, rejection, and shorter graft survival.

CMV may also pave the way for other opportunistic infections. Post-transplant, patients are placed on prophylaxis treatment to prevent CMV. Valganciclovir or ganciclovir are the prophylactic drugs of choice. As these medications are expensive, the transplant social worker works closely with the patient before the transplant to ensure that plans are in place to pay for the drugs for the entire regimen.

BKV is another viral infection that can affect the kidney transplant patient. After a kidney transplant, BKV can cause hemorrhagic cystitis, tubulointerstitial nephritis, BKV-associated nephropathy (BKVAN), and graft failure. It is recommended to do BKV screening every one to three months for the first two years posttransplant, then yearly through the fifth year.

Should BKVAN occur, the most widely used treatment is to decrease the immunosuppressive maintenance therapy. This may include switching from one drug to another or withdrawing part of the drug regimen for a specific period. Though not as common, the use of leflunomide, ciprofloxacin, or intravenous Ig has also been used to combat BKVAN (23).

Recurrence of Native Kidney Disease

There are times when the very disease that caused a patient’s kidney to fail in the first place attacks the allograft as well. Graft loss due to native kidney disease has historically occurred around 8.4% ten years after transplant. This rate has long been thought to be underestimated due to the vast difference in facility protocols, methods, and reporting (26).

Rejection

Though there have been great strides in immunosuppressive therapies, organ rejection continues to be a leading cause of allograft failure. Episodes of acute rejection can either be T-cell-mediated or antibody-mediated. T-cell mediated rejection is usually the type of rejection that occurs in the first year after transplant. After the first year, antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) is more common.

Inadequate immunosuppressive therapy, non-adherence to the therapy, or a decrease in immunosuppressive therapy are the causes of acute rejection. Symptoms that would cause the provider to suspect acute rejection would include increasing creatinine, decreased urine output, swelling of the extremities, pain over the allograft site, and generalized flu-like symptoms.

When these symptoms are present, the provider may opt to perform an allograft biopsy. The biopsy is the only definitive method to diagnose allograft rejection. Episodes of acute rejection have an overall negative impact on long-term allograft survival.

The persistence, severity, and histologic type of rejection will play a part in determining the length of survival of the allograft. Again, AMR is proven through allograft biopsy along with the presence of donor-specific antibodies (DSA) against donor HLA antigens.

There are a few different treatments for AMR to remove the DSAs and decrease their further production. The exchange of plasmapheresis and the use of the drug Rituximab are among such treatments (9, 10, 19).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name two possible complications post-transplant?

- What are the two causes of acute rejection?

- What are two symptoms of acute rejection?

- What is the most critical infection after transplant?

- What drug is used for CMV prophylaxis?

Medications and Treatments

Tacrolimus

Discovered in 1984 and first used as an immunosuppressive therapy agent in 1989, tacrolimus has become the first-line immunosuppressive drug of choice for kidney transplant. Tacrolimus is an immunosuppressant that works by inhibiting the calcineurin-dependent pathway. Blood levels of tacrolimus are monitored regularly to ensure that they are therapeutic.

Based on the levels, the dose of tacrolimus may be adjusted to obtain the desired therapeutic levels. As the dosage may be changed depending on the level, tacrolimus must be taken at the same time every day. Tacrolimus interacts with other drugs and foods; it is, therefore, important that some drugs and foods are avoided so that the potency of tacrolimus is not affected.

Ironically, tacrolimus is used to prevent kidney transplant rejection, yet it is nephrotoxic. This is another reason why monitoring tacrolimus levels is so important (14).

Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF)

MMF is another immunosuppressant drug that is most often used in conjunction with tacrolimus as part of the dual drug regimen. MMF is an inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibitor. It also suppresses primary antibody responses. Blood drug levels are not typically monitored. However, in cases of acute rejection, the provider may want to find out what the MMF level is (2).

Thymoglubulin [Anti-thymocyte globulin (rabbit)]

Induction immunosuppressive therapy is initiated in the operating room at the time of transplant to decrease the incidence and severity of acute rejection episodes. It also allows the physician to delay the maintenance of immunosuppressants as needed depending on the patient’s condition.

Thymoglubulin is the most common induction therapy used in the United States. How Thymoglobulin works is by depleting T-cells. The effects of the Thymoglobulin induction dose can last for three months. Patients who receive Thymoglobulin must be carefully monitored during this time for infection (3).

Valganciclovir

CMV is the most common viral infection after a kidney transplant. The most likely reason for this is a reactivation of the recipient’s latent CMV virus once the patient is immunosuppressed. In other cases, the patient may receive the allograft from a donor that previously had CMV, and it becomes reactivated in the recipient.

Measures must be taken to prevent this infection from happening. Valganciclovir, an anti-viral, is the prophylactic agent of choice to prevent CMV. There are two widely used strategies in the administration of valganciclovir. It may be administered immediately after transplant for three months, or the treatment may be started once the virus is detected.

Typically, monitoring blood levels of valganciclovir is not common practice. However, recent studies have indicated that there may be benefits to monitoring these levels and, in doing so, the provider may be able to predict if and when a CMV infection is imminent. More studies are needed to explore this topic further (25).

Rituximab

Rituximab is a drug that is used for the treatment of allograft rejection. It is a B-cell-depleting drug. Studies have shown that, when used alone, the efficacy of Rituximab has been called into question. However, when used as a part of a multimodal regimen including steroids, plasmapheresis and IVIG, the effects of the use of Rituximab have proven to be quite positive (19).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Name the two most common drugs used to prevent rejection.

- How is the dose of tacrolimus determined?

- What is Thymoglobulin and how long do the effects of Thymoglobulin last?

- What does Rituximab treat?

Patient Education

Patient education is an aspect of transplant that starts on the initial clinic visit and continues throughout the entire transplant process. The patient needs to understand that a kidney transplant is a life-long commitment. The transplanted is a gift and a new lease on life that must be respected and cherished. Education on compliance and adherence to the pre-transplant testing is key.

Noncompliance with any testing the transplant clinic requires or reported noncompliance by the patient’s dialysis center is a “red flag” that indicates a patient may not be compliant with the required care after the transplant. This may be discussed with the Selection Committee. Once listed, the patient is educated on the waitlist process. They need to understand what the average wait time is. Teaching the benefits of live versus deceased donation and encouraging them to seek out a live donor could lead to finding a suitable donor and speed up the overall transplant process.

While on the waitlist, the patient must also maintain their health. Reporting any new infection, malignancy or other progression of disease is important as it may affect the ability to receive a kidney transplant. After the transplant, the patient is educated on all the new medications that they will be taking. Special focus is given to the anti-rejection drugs. The patients must understand that by not taking these medications exactly as prescribed, they are placing the allograft at risk.

Knowing the signs and symptoms of rejection is also a key point of the education process. Hydration is key. When in ESRD, patients are taught to limit their fluid intake. After the transplant, fluids are essential. Patients have to be taught and encouraged to increase their fluid intake. Patients also need to be taught about other lifestyle changes that need to be made to prolong allograft survival for as long as possible.

Diet, exercise, pets, and habits and how they impact the kidney have to be taken into account. Having veteran transplant recipients come in and speak with the newer recipients has proven to be very positive. When the newer recipients learn from veteran’s experiences, it becomes more meaningful and real to them (4).

Case Study

A 45-year-old Hispanic male came to the transplant clinic for his initial appointment. He has a history of diabetes leading to ESKD and hypertension. As a result of ESKD, he started dialysis four years ago.

Vital signs:

- Height: 5’10”

- Weight: 205 lbs.

- BMI: 29.4

- BP: 176/101

- HR: 78 bpm

- RR: 18

- Temp.: 97.5

The head-to-toe assessment yielded the following abnormal findings:

- Two teeth with rot noted.

- Multiple abnormal moles on his back.

- The right pedal pulse was faint. Decreased hair growth on the right leg.

- When the lab work came back, the patient’s PSA was 6.1.

He states that he sometimes signs out of dialysis early due to fatigue. He also does not take his phosphate binders regularly as he has trouble swallowing them.

The patient’s spouse came with him. She works part-time and is generally able to get time off to take the patient to his appointments.

They also have a son who has already committed to taking time off work to stay with the patient at the time of transplant.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why are signing out of dialysis early and not taking the phosphate binders significant?

The transplant physician ordered the following testing appointments:

- CXR, CT of the abdomen and pelvis

- Colonoscopy

- Cardiology consult with EKG and cardiac catheterization with bilateral run-off

- Urology consult to evaluate the prostate

- Dermatology consult to evaluate the abnormal moles

- Dental consult for extraction of the rotten teeth and general evaluation of dental health

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What factors will determine this patient’s wait time?

- Why do rotten teeth need to be addressed?

- Why do the abnormal moles need to be addressed?

- Why was this patient’s support system evaluated?

When all the testing results and appointment notes were received, they were reviewed by the transplant physician. All the patient information was compiled, and the patient’s case was brought to the selection committee. At the selection committee, the pre-transplant testing was reviewed, and each member discussed the patient’s case from their point of view.

The committee voted unanimously to accept the patient’s candidacy for transplant and place him on the UNOS kidney transplant waitlist. The patient waited for three years before getting his first kidney offer. Yearly, he came back to the transplant center to be re-evaluated to make sure that he was still a good candidate for transplant and that all his resources were still in place.

In the third year after being placed on the waitlist, a kidney offer came in, and he was transplanted. The transplant nephrologist and coordinator reviewed the offer and decided that it was an acceptable kidney for this patient. The offer was accepted, and they coordinated the arrival of the patient and the kidney to the hospital. When the patient arrived, the coordinator met him in his room and started the post-transplant education process.

The surgery was a success, and his in-hospital recovery went very well. On discharge from the hospital, the transplant coordinator went to see the patient. Thorough teaching on medications, rejection, and infection was done. The coordinator also brought in all the discharge medications and had the patient fill his pillbox for the next two days (on the third day, he will be in the clinic).

Among his new medications were tacrolimus, MMF, prednisone, valganciclovir, Bactrim, Pepcid, magnesium, folic acid, and Toprol. The first month of recovery went very well without any major complications. On one visit, the creatinine went up. The patient hadn’t been hydrating as needed.

The patient was given an IV bolus of normal saline in the clinic and the creatinine was back to normal the next day. After a year of being seen at the transplant clinic, the care was handed back over to the patient’s regular nephrologist.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- When did the Selection Committee meet to discuss this patient’s case?

- When was the post-transplant education started?

- When did the patient receive his new medications? Who brought them?

- Why did the patient receive a bolus of normal saline in the transplant clinic?

Conclusion

A kidney transplant is not just surgery, it is a complex process that involves the patient, their family, the multidisciplinary transplant team, and multiple other providers who help confirm or rule out the patient’s candidacy for transplant. From the initial appointment, patient education is a heavy focus.

As the transplant process is complex, the patient and their support system need to be aware of and understand the transplant clinic’s expectations of them and align their expectations to the reality of the transplant process. Once through the process and the transplant has taken place, the result is life changing. Both the quality and the expected longevity of life increase dramatically.

Again, education is key. Adherence to their new lifestyle and medication regimen will increase the odds that the allograft will survive for many years.

References + Disclaimer

- Adler, J. T., Husain, S. A., King, K. L., & Mohan, S. (2021). Greater complexity and monitoring of the new kidney allocation system: Implications and unintended consequences of concentric circle kidney allocation on network complexity. American Journal of Transplantation, 21(6), 2007–2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.16441

- Allison, A. C., & Eugui, E. M. (2000). Mycophenolate mofetil and its mechanisms of action. Immunopharmacology, 47(2-3), 85–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00188-0

- Alloway, R. R., Woodle, E., Abramowicz, D., Segev, D. L., Castan, R., Ilsley, J. N., Jeschke, K., Somerville, K., & Brennan, D. C. (2019). Rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin for the prevention of acute rejection in kidney transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation, 19(8), 2252–2261. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.15342

- Andersen, M., Wahl, A., Engebretsen, E., & Urstad, K. (2019). Implementing a tailored education programme: Renal transplant recipients’ experiences. Journal of Renal Care, 45(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/jorc.12273

- Chadban, S. J., Ahn, C., Axelrod, D. A., Foster, B. J., Kasiske, B. L., Kher, V., Kumar, D., Oberbauer, R., Pascual, J., Pilmore, H. L., Rodrigue, J. R., Segev, D. L., Sheerin, N. S., Tinckam, K. J., Wong, G., & Knoll, G. A. (2020). Kdigo clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and management of candidates for kidney transplantation. Transplantation, 104(4S1), S11–S103. https://doi.org/10.1097/tp.0000000000003136

- Claisse, G., Gaillard, F., & Mariat, C. (2020). Living kidney donor evaluation. Transplantation, 104(12), 2487–2496. https://doi.org/10.1097/tp.0000000000003242

- Data and trends. (2023, December 2). UNOS. Retrieved December 2, 2023, from https://unos.org/data/

- Hameed, A. M., Yao, J., Allen, R., Hawthorne, W. J., Pleass, H. C., & Lau, H. (2018). The evolution of kidney transplantation surgery into the robotic era and its prospects for obese recipients. Transplantation, 102(10), 1650–1665. https://doi.org/10.1097/tp.0000000000002328

- Hariharan, S., Israni, A. K., & Danovitch, G. (2021). Long-term survival after kidney transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(8), 729–743. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra2014530

- Hart, A., Singh, D., Brown, S., Wang, J. H., & Kasiske, B. L. (2021). Incidence, risk factors, treatment, and consequences of antibody‐mediated kidney transplant rejection: A systematic review. Clinical Transplantation, 35(7). https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.14320

- Mannon, R. (2018). Delayed graft function: The aki of kidney transplantation. Nephron, 140(2), 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1159/000491558

- Martínez, V., Furlano, M., Sans, L., Pulido, L., García, R., Pérez-Gómez, M., Sánchez-Rodríguez, J., Blasco, M., Castro-Alonso, C., Fernández-Fresnedo, G., Robles, N., Valenzuela, M., Naranjo, J., Martín, N., Pilco, M., Agraz-Pamplona, I., González-Rodríguez, J., Panizo, N., Fraga, G.,…Cabezas, A. (2022). Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in young adults. Clinical Kidney Journal, 16(6), 985–995. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfac251

- Neuwirt, H., Rudnicki, M., Schratzberger, P., Pirklbauer, M., Kronbichler, A., & Mayer, G. (2019). Immunosuppression after renal transplantation. memo – Magazine of European Medical Oncology, 12(3), 216–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12254-019-0507-4

- Ong, S. C., & Gaston, R. S. (2020). Thirty years of tacrolimus in clinical practice. Transplantation, 105(3), 484–495. https://doi.org/10.1097/tp.0000000000003350

- Ossareh, S., Yahyaei, M., Asgari, M., Bagherzadegan, H., & Afghahi, H. (2021). Kidney outcome in primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) by using a predictive model. Iranian Journal of Kidney Diseases, 15(6), 408–418. https://doi.org/10.52547/ijkd.6442

- Parikh, S. V., Almaani, S., Brodsky, S., & Rovin, B. H. (2020). Update on lupus nephritis: Core curriculum 2020. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 76(2), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.10.017

- Pugliese, G., Penno, G., Natali, A., Barutta, F., Di Paolo, S., Reboldi, G., Gesualdo, L., & De Nicola, L. (2019). Diabetic kidney disease: New clinical and therapeutic issues. joint position statement of the italian diabetes society and the italian society of nephrology on “the natural history of diabetic kidney disease and treatment of hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes and impaired renal function”. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 29(11), 1127–1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2019.07.017

- Schaffhausen, C. R., Bruin, M. J., McKinney, W. T., Snyder, J. J., Matas, A. J., Kasiske, B. L., & Israni, A. K. (2019). How patients choose kidney transplant centers: A qualitative study of patient experiences. Clinical Transplantation, 33(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.13523

- Schinstock, C. A., Mannon, R. B., Budde, K., Chong, A. S., Haas, M., Knechtle, S., Lefaucheur, C., Montgomery, R. A., Nickerson, P., Tullius, S. G., Ahn, C., Askar, M., Crespo, M., Chadban, S. J., Feng, S., Jordan, S. C., Man, K., Mengel, M., Morris, R. E.,…O’Connell, P. J. (2020). Recommended treatment for antibody-mediated rejection after kidney transplantation: The 2019 expert consensus from the transplantation society working group. Transplantation, 104(5), 911–922. https://doi.org/10.1097/tp.0000000000003095

- Shabaka, A., Tato Ribera, A., & Fernández-Juárez, G. (2020). Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: State-of-the-art and clinical perspective. Nephron, 144(9), 413–427. https://doi.org/10.1159/000508099

- Soriano, R. M., Penfold, D., & Leslie, S. W. (2023). Anatomy, abdomen, and pelvis: Kidneys. http://europepmc.org/books/NBK482385

- UNOS transplant living. (2023, December 2). UNOS. Retrieved December 2, 2023, from https://transplantliving.org/kidney/the-kidney-transplant-waitlist/

- Vanichanan, J., Udomkarnjananun, S., Avihingsanon, Y., & Jutivorakool, K. (2018). Common viral infections in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Research and Clinical Practice, 37(4), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.23876/j.krcp.18.0063

- William, J. H., Morales, A., & Rosas, S. E. (2020). When eskd complicates the management of diabetes mellitus. Seminars in Dialysis, 33(3), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/sdi.12873

- Wong, D. D., van Zuylen, W. J., Craig, M. E., & Rawlinson, W. D. (2018). Systematic review of ganciclovir pharmacodynamics during the prevention of cytomegalovirus infection in adult solid organ transplant recipients. Reviews in Medical Virology, 29(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2023

- Yamamoto, I., Yamakawa, T., Katsuma, A., Kawabe, M., Katsumata, H., Hamada, A., Nakada, Y., Kobayashi, A., Yamamoto, H., & Yokoo, T. (2018). Recurrence of native kidney disease after kidney transplantation. Nephrology, 23(S2), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.13284

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click the Green MARK COMPLETE Button Below

To receive your certificate