Course

Opioid Use in the Terminally Ill

Course Highlights

- In this Opioid Use in the Terminally Ill course, we will learn about the impact that the opioid crisis has had on terminally ill patients.

- You’ll also learn to summarize fears associated with opioid use.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of opioids recommended for cancer-related pain.

About

Contact Hours Awarded:

Course By:

Charmaine Robinson

MSN-Ed, BSN, RN, PHN, CMSRN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

Patients who are terminally ill often experience pain that worsens as they approach death. The opioid crisis in the U.S. may have made it difficult for clinicians to manage pain in patients who are terminally ill. While opioid prescription regulation may benefit some patients by preventing overdoses, research suggests that patients with terminal illnesses may suffer on the back end.

In this course, we will delve into pain statistics, the common opioids used at the end of life, fears and stereotypes, the importance of continual assessments, and proven pain relief strategies. Although most information you may find on opioid use at the end of life focuses on pain in patients with cancer, many of the same principles may be applied to other terminal illnesses, including end-stage organ failure and progressive diseases/conditions.

Pain in Terminally Ill Patients

Many people who have terminal illnesses experience troubling symptoms at the end-of-life, particularly pain. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) – a global organization of researchers and clinicians advocating for pain relief – defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” [16]. Pain may be physical, emotional, and/or spiritual and is often underrecognized and undertreated [19, 21]. Multiple studies over the years have shown pain to be a significant concern in patients who are terminally ill.

According to a 2020 study in BMC Palliative Care, patients with terminal illnesses were significantly more likely to report severe daily pain than those with other chronic conditions [13]. In the study, researchers reviewed pain assessments that were performed for 20,349 patients in the last months of life. Results showed that approximately 42% of the patients reported pain that disrupted their usual activities.

The report also highlighted findings from several other studies indicating that pain at the end-of-life is a significant problem. One of the studies – a systemic review of additional studies between 1965 and 2006 – concluded that 64% of patients with advanced cancer reported pain. Another study found that of the 4703 people sampled, 47% had clinically significant pain in the last month of life. A final study found that one in ten emergency room (ER) visits from patients with cancer at the end-of-life were related to pain.

A 2020 report in Home Healthcare Now also highlighted findings from several studies that supported the significance of pain in terminally ill patients, particularly those with end-stage chronic diseases and cancer [19]. One of the studies found pain to be the second most prevalent distressing symptom in the last two weeks of life (after terminal dyspnea). Another – a longitudinal study spanning from 1998 to 2010 – found an increase in the presence of pain in patients at the end-of-life (from 54% to 61%).

A final study revealed that 81% of terminally ill patients reported “being pain-free” as the most important element of a “good death.” Pain is considered one of the greatest fears among patients diagnosed with terminal illnesses [19].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is your experience with patients who have terminal illnesses?

- Why do you think that pain is often underrecognized?

- How well do you think the healthcare system addresses pain in patients who are terminally ill?

- What are some terminal diseases/conditions, unrelated to cancer, that may cause chronic pain?

Impact of Pain on Quality of Life

Quality of life can be described as a person’s overall wellbeing and may include physical health, functional status, psychological health, and sleep. Multiple studies have shown that pain impacts the quality of life for many patients. Unmanaged pain can cause distress in both patients and their family caregivers, and the problems that result often overlap [19]. The following are ways in which pain may impact the quality of life for patients who are terminally ill.

Psychological Distress

Pain can be severe for patients at the end-of-life. Therefore, pain control is imperative. When pain is not managed properly, patients can suffer psychological distress that can lead to detrimental outcomes. Psychological distress in patients at the end-of-life can manifest as feelings of hopelessness, sadness, desperation, and anguish, particularly if the pain is unbearable [11].

Psychological distress can lead to mental illnesses if not addressed. Patients may be at risk for cognitive decline and depression if pain is not properly assessed and treated [11]. Pain-related depression can lead to even more pain which perpetuates a vicious cycle [12]. The psychological distress at the end-of-life can play a significant role in a patient’s mood, social life, ability to sleep, and spiritual coping.

Spiritual Distress

Spiritual pain in patients at the end-of-life may encompass elements of religion, existentialism, and/or a sense of life meaning. In 1986, Cicely Saunders – a pioneer in terminal care research – defined spiritual pain as “a desolate feeling of meaninglessness” [15]. Other definitions of spiritual pain began to surface over the years including those related to internal conflicts (like guilt, despair, and loss), disconnect from others, feelings of annihilation and separation, and overall life satisfaction [15]. For patients at the end-of-life, spiritual distress may be caused by psychological stressors that result from physical pain, or by psychological pain alone.

In a 2022 study in Palliative Care and Social Practice, a relationship was identified between psychological pain and spiritual coping [11]. Spiritual pain or suffering may be caused by pain-related psychological distress which may be associated with fear and uncertainty. Researchers noted that patients who are terminally ill, and their families, may struggle with feelings of anguish related to the uncertainty of a cure, fear of treatment (i.e., chemotherapy and radiation), pain, future hospitalizations, suffering, and death.

While pain can cause spiritual distress, patients may be able to maintain a sense of hope. Researchers in the study found that the feeling of hope, in patients with advanced staged cancer, is more related to the psychosocial elements of the pain experienced rather than to the actual intensity of pain. This means that although cancer-related pain may worsen over time, patients are still able to maintain a sense of hope based on their resilience, and psychosocial and spiritual resources [11].

Functional Decline

Functional status (or capacity) involves a person’s ability to perform activities of daily living and meet their own needs. Chronic physical pain can cause restrictions on activity, and the ability to work and perform routine tasks which may leave many patients feeling frustrated, angry, and depressed [12]. For patients with terminal illnesses, activity changes can be caused by more than the chronic pain they may experience. The psychological distress caused by unmanaged pain can cause functional declines in this group [14, 16].

Sleep Problems

Sleep is an integral part of health and wellness. Disruption of sleep can lead to a poor quality of life for many patients [6]. Findings from a 2019 study in the Journal of Patient Experience suggested that chronic pain had a negative impact on patients’ ability to sleep, maintain sleep, and enjoy a good quality of sleep [12]. For patients with terminal illnesses, lack of sleep may be related to more than the physical pain of the disease. Patients with advanced cancer, in particular, suffer from insomnia related to both pain as well as treatments and other physical and psychological symptoms [6, 11].

In a 2019 study in Clinical Medicine, researchers found that many patients with advanced cancer met the diagnostic criteria for short-term insomnia disorder and chronic insomnia disorder (three months of sleep problems that occur at least three times a week) [6]. The study found that sleep problems can even lead to progression of the disease. Insomnia has been associated with a lower response to chemotherapy, decreased survival, and progression of cancers [6].

Social Impairments

Patients who experience pain due to terminal illness may have challenges with social relationships. A patient’s experience of chronic pain can result in physical functional limitations that interfere with a healthy social life. In the previously mentioned Journal of Patient Experience study, patients described the impact of chronic pain on physical functioning as the main cause of professional, family, and social life difficulties [12].

Pain-related psychological stressors are often the driving factors for social difficulties in patients who are terminally ill. Human suffering from cancer pain, in particular, can cause feelings of uselessness [11]. These feelings may impact a patient’s desire to socialize or interact with others. Patients may also have difficulty bonding with care team members, ultimately impacting overall quality of life [11].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How have your patients described the impact of chronic pain on their personal lives?

- What types of spiritual dilemmas in patients have you come across in your practice?

- Have you experienced caring for a patient who was depressed due to a terminal diagnosis?

- Have you ever experienced a challenging family issue related to end-of-life care?

Opioid Crisis: Nationally and Globally

The U.S. continues to face an opioid drug crisis. Three million people in the U.S. are dependent on opioids [8]. Addictions are only part of the problem. Deaths related to opioids are considered the most lethal drug epidemic in U.S. history [8]. In 2021, over 50,000 people died from a drug overdose, and approximately 82% involved at least one opioid [25].

Prescription opioids in particular have been a source of concern. Of the 20 million people in the U.S. who misuse substances, two million are using prescription opioid pain medications [8]. From 1999 to 2021, approximately 280,000 people in the U.S. died from overdoses related to prescription opioids alone [26].

The U.S. is not alone in the opioid crisis as dependency on opioids is a worldwide problem. Globally, 16 million people are dependent on opioids [8]. In 2019, approximately 600,000 deaths worldwide were attributed to drug use, nearly 80% were related to opioids, and an overlapping 25% were caused by opioid overdoses in particular [29]. Further, only half of all countries worldwide offer treatment for opioid dependency and less than 10% of the people who need help are receiving treatment for it [29].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- In what ways does your workplace or community bring awareness to the opioid crisis?

- In your opinion, how does society’s opinion about opioid use play a role in the current opioid crisis?

Opioid Crisis: Impact on Terminally Ill Patients

Patients with life-limiting illnesses often need higher doses of pain medications as the disease progresses. Nearly 30% of patients with cancer take more than one opioid in the last three months of life, and exceptionally high doses in the final week [18]. However, the opioid crisis may have led some providers to cut back on prescribing.

To help combat the opioid crisis, the U.S. introduced electronic prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) to help track the number of opioids prescribed to patients to prevent overprescribing and patients’ use of multiple health providers [24]. PDMPs may have contributed to some health providers’ hesitation with prescribing opioids [9]. One study suggests that these regulatory changes may have led to limited opioid access for patients with terminal cancer.

A 2021 study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology found that older adult patients with advanced cancer nearing the end-of-life had limited access to opioid medications for pain management between 2007 and 2017 [9]. Results showed a 40% decrease in the total amount of opioids prescribed for this group, a 15.5% decrease in the proportion of patients who received an opioid near the end-of-life, and a 36.5% decrease in the proportion of patients receiving long-acting opioids.

Similar to other reports, the study also found a 50% rise in pain-related ER visits in this group, although researchers were unable to determine whether the ER visits were prompted by cancer-related pain specifically.

In the study, the decline in “opioid prescribing” was described in three ways: the number of prescriptions, potency of prescriptions, and use of long-acting opioids. Declines in long-acting opioid prescribing were most substantial. Long-acting opioids are most heavily regulated as they are the most likely to be misused [9]. This serves as a threat to effective pain management in patients with advanced malignant disease as long-acting opioids are the ideal choice for pain management in those who are terminally ill [19].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What has been your experience with patients who have uncontrolled pain?

- What is your facility’s protocol for relieving pain in patients who are terminally ill?

- Have you ever accessed a prescription monitoring database (or witnessed a physician using one)?

- Has a physician ever refused to prescribe an opioid for a patient who was terminally ill under your care?

Fears Influencing Opioid Use

Today, opioid use is often met with public fear and hesitation. Misconceptions about opioid use from patients, their caregivers, and clinicians may lead to suboptimal pain management at the end-of-life. The following fears can serve as barriers to effective pain management.

Fear of Stigmatization

Studies have shown that patients with advanced cancer often fear being stigmatized by healthcare providers and the general public when taking opioids for pain. In a 2021 report in JCO Oncology Practice, researchers studied oncologists’ experiences with opioid use in patients with advanced cancer about the opioid crisis [20]. Results indicated that patients who received opioids for pain felt stigmatized by clinicians, pharmacists (when picking up their prescriptions), and society as a whole. Patients also feared becoming addicted to opioids and being labeled “addicts,” affecting their willingness to receive prescriptions.

Fear of Addiction or Dependence

It is well-known that opioid use can lead to addiction. However, fears and misconceptions about its use may lead to inadequate pain control. More specifically, a patient’s adherence to pain medication orders may be highly influenced by their personal beliefs about opioids [11]. Many studies have reflected this fact.

In a 2020 study in Palliative Medicine, patients with advanced-stage cancer and their caregivers were asked for their opinions on opioid use [14]. Both were questioned on their perceptions of morphine use, attitudes toward future morphine use for cancer-related pain, reasons behind perceived barriers to using morphine, and the influence of one another’s views on the other’s acceptance of morphine use.

The study found that although patients and caregivers believed morphine to be an effective strategy for pain control, some felt that morphine use implied disease progression and hopelessness. Others believed morphine had addictive properties, would lead to tolerance with repeated use, and should be used only as a last resort. A few participants were concerned about the negative side effects of morphine.

While fear of addiction may be valid as opioid addiction does occur in patients who are terminally ill, psychological dependency and cravings rarely occur in those who do not already have a history of drug misuse [3]. However, chemical dependency can occur when pain is also being managed in other ways, for example, radiation therapy in patients with cancer. In this case, the opioids should be titrated gradually.

Fear of Respiratory Depression

Some patients, families, and clinicians may fear taking/administering an opioid for pain management due to the potential for respiratory depression. While it is true that opioids can have this effect, when opioid doses are titrated according to the patient’s pain (particularly in patients with cancer), significant respiratory depression rarely occurs [3]. This is due to pain serving as an antagonist to the depressant effects of opioids on breathing [3]. Essentially, when a patient with cancer is in pain, they are less likely to experience respiratory depression from opioids. For this reason, opioid doses should be adjusted according to the patient’s pain. Additionally, when other approaches for pain relief are added (for example, chemotherapy or radiation), opioid doses need to be titrated accordingly.

Fear of Hastened Death

In patients at the end-of-life, opioid doses and frequency often increase as the disease progresses. In many cases, morphine is not even initiated until the disease has progressed [3]. For this reason, many patients and families may believe that opioids hasten death when in fact, the patient’s worsening disease is likely the culprit. Research shows that morphine has the potential to prolong life if prescribed early [3]. However, this life-prolonging attribute is related to morphine’s effectiveness in pain relief, which helps patients sleep and eat better, increase their activity level, and ultimately have a better quality of life.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever witnessed a coworker stigmatize a patient who used opioids for pain?

- What are some fears you have about administering opioids?

- Have you ever had to challenge a misconception a family member had about opioid use?

- What is the most common opioid administered for pain at your facility?

Care Team Limitations of Opioid Use

Patients who are terminally ill have to cope with their illness, prognosis, pain, stereotypes and fears surrounding opioid use. If not careful, the care team can become an added burden for this group.

Many care team members’ attitudes, lack of knowledge, and suboptimal reassessments surrounding opioids and pain can negatively impact patients who are terminally ill. In addition, poor communication between providers and patients can lead to patients feeling anxious, frustrated, helpless, and angry [11].

Pain in cancer, in particular, is often difficult to understand due to its subjectivity; therefore, it is often underdiagnosed and undertreated [11]. Care team members may be unaware of the pain their patients are experiencing. One report revealed that many oncologists do not regularly ask their patients about pain, and pain evaluations are rarely documented. [11]. The report also found that while there are tools available (like scripts) that can help patients with terminal illnesses express their pain, worries, and needs, many are simply not used.

As mentioned earlier, another barrier is the opioid crisis and the subsequent regulations, which may have led to hesitancy in prescribing opioids.

Educating the care team may serve as a way to address these barriers. In a 2020 systematic review in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, researchers assessed the influence of education on pain management in various healthcare settings, including inpatient care, home hospice care, general home care, oncology and palliative care clinics, and an HIV clinic [4].

Cognitive-behavioral-based and role-playing training sessions were provided to patients and their family caregivers to help build problem-solving, assertiveness, and communication skills that would be useful in managing pain. Nurses were included in the role-playing sessions. Although the training sessions were intended for and ultimately benefited patients and their families, nurses’ perception of pain had significantly improved.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How often are nurses required to perform pain reassessments at your facility?

- Was there ever a situation in which you significantly underestimated a patient’s pain?

- How has your experience been with patients who struggle asking for pain medication?

- How often does your facility provide education on opioid use in patients?

Cognitive Impairments and Pain-Reporting

Pain management becomes complicated when patients who have terminal illnesses have a difficult time communicating their needs. In general, a patient’s ability to communicate wanes as they near death, particularly in the last week of life.

Communication capacity has been found to decrease to 43% five days before death, 28% three days before, and 13% the day before death [19]. Cognitive impairments, in particular, can serve as barriers to pain-reporting in this group. Approximately 20% of patients at the end-of-life who have intact cognition report severe daily pain compared to only 13% with severe cognitive impairment [13].

While these patients may indeed have severe pain as they approach death, cognitive impairments can limit their ability to express or verbalize the pain. For this reason, patients who are cognitively impaired should be assessed regularly for physical signs of pain.

Patient/Family Education: Influence on Pain Outcomes

Effective education on pain management among patients who are terminally ill can lead to better outcomes for both the patients and their families. In the previously mentioned systematic review in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management (addressing role-playing training sessions for pain management), researchers also studied the effect that education in the form of written materials, face-to-face instruction, and coaching had on patient outcomes. Most of the studies in the review had a sample size of over 100 participants. Nearly 45% of the studies focused on hospice and palliative care, and an overlapping 68% on cancer. Of the cancer-specific studies, approximately one-fifth focused on advanced-stage cancer.

Patients and families were educated on pain reporting and assessment, strategies to relieve pain (including non-pharmacological treatments), medications, and misconceptions about pain management. In most studies, significant improvements in patient outcomes were noted when education was provided on specific aspects of pain management, including pain intensity, impact of pain on daily living, misconceptions, adherence to prescribed pain medications, psychological well-being, and overall quality of life.

The studies found that family caregivers’ outcomes significantly improved as well, evidenced by obtaining knowledge, gaining motivation and self-efficacy in pain management, and expressing fewer concerns about managing their loved one’s pain.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do you assess pain in patients who have cognitive impairments (like dementia)?

- How often do you care for patients who are terminally ill and do not require pain medications?

- Do you find that patient and family training leads to better adherence to medications?

- How do you address situations in which family members are resistant to teaching?

Introduction to Opioid Safety Guidelines

National and global organizations and groups often develop guidelines as a standard for practice, many times targeting specific groups of patients. Guidelines are intended to keep patients safe and ensure the provision of high-quality care. Over the years, opioid safety guidelines have been developed across the globe for the general population due to the rise in opioid use disorders and drug overdoses.

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released the Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain which was eventually updated in 2022 to the Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain. The guideline was intended to assist health providers in making informed decisions regarding pain management with opioids by outlining whether or not to initiate opioids for pain, how to select the most appropriate opioid types, doses, and durations, and how to assess for risks of harm associated with opioid use [27]. While this guideline may help manage pain and ensure the safety of many patients, it is not recommended in the care of patients at the end-of-life or those with cancer.

The pain experienced by patients with terminal illnesses can be complex and therefore requires special management. Providers specializing in terminal care may refer to the World Health Organization (WHO) Analgesic Ladder for pain management in patients with cancer, and the North American Opioid Safety Recommendations in Adult Palliative Medicine for guidance on opioid safety in palliative care patients. These will be discussed in the upcoming sections.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- In your facility, where can nurses find information on medications?

- Is there a special protocol in place at your facility that guides the care of patients with terminal illnesses?

- In your opinion, are global practice guidelines relevant to patient care in the U.S.?

Opioid and Non-Opioid Medications

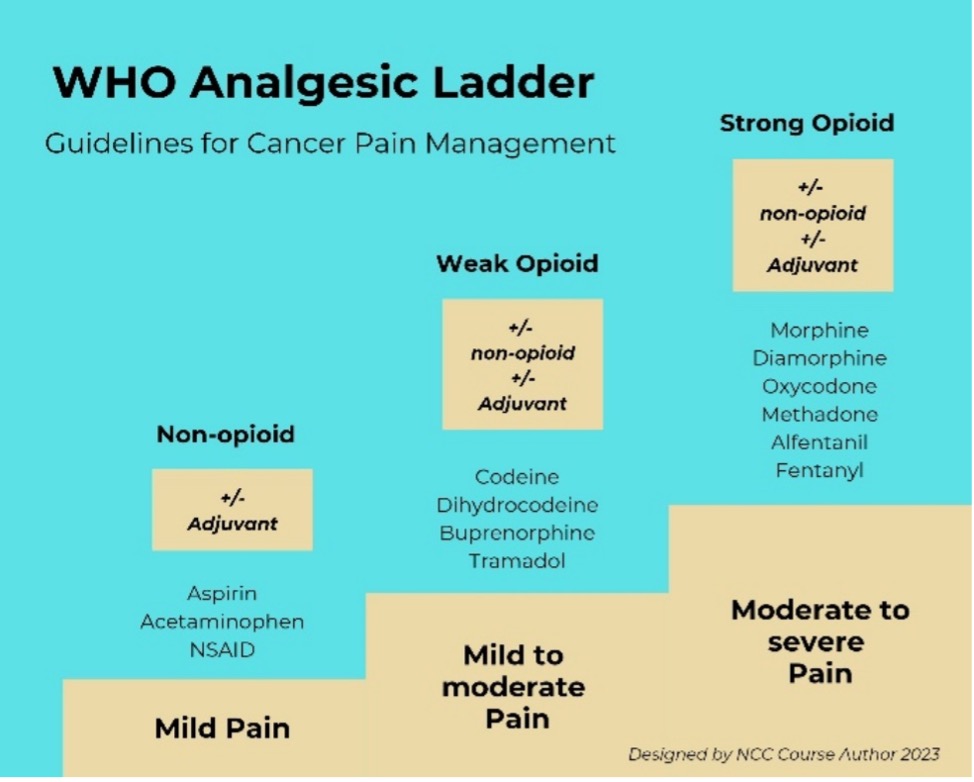

In 1986, the World Health Organization designed a Three-Step Analgesic Ladder – a guideline intended to help providers choose the best medication to manage pain in patients with cancer [See Figure 1]. In 2019, the Ladder was revised to include a fourth step that includes non-pharmacological/interventional therapies (i.e., nerve blocks, ablations, palliative radiation, non-invasive neurosurgical procedures, etc.) [2].

For the sake of this course, we will focus on the original three steps. Although the guideline has critics, it is often referenced as a source for cancer-related pain control and is said to control up to 80% of a patient’s pain [28]. Some organizations have developed their own set of guidelines derived from the Analgesia Ladder, for example, the European Society of Medical Oncology’s (ESMO) 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines on Cancer Pain.

Providers who care for patients with terminal cancer may refer to the WHO Analgesic Ladder for guidance when managing pain in this group. However, providers should recognize that the Analgesic Ladder is simply a foundational recommendation for practice. Medication prescribing should be tailored to each patient’s pain experience. The ladder addresses the following three pain intensity levels and recommends both opioid and nonopioid medications as strategies for pain relief [10, 28].

Figure 1: World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder [28]

Mild Pain (Non-opioids)

Non-opioid medications fall under the first and second rungs of the WHO Analgesic Ladder. While non-opioid medications can be used at any level of pain (mild, moderate, or severe), the WHO recommends these types of medication to be used primarily for mild cancer-related pain. Non-opioids commonly used in the U.S. may include acetaminophen and NSAIDs.

- Acetaminophen: Although there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of acetaminophen for cancer-related pain, the WHO recommends it as one of the first line of choice medications for mild pain. Acetaminophen should be monitored as it can lead to hepatotoxicity [21].

- NSAIDs: NSAIDs are also considered a first choice for mild cancer-related pain and may include Ibuprofen and Ketorolac. NSAIDs work by inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandins – hormone-like compounds that control inflammation and pain in the body [21]. NSAIDs should be monitored as they have the potential to cause platelet dysfunction, gastrointestinal, cardiac, and renal complications with extended use [10]. While NSAIDs alone may be effective in pain relief of patients with cancer, most patients take these medications in conjunction with opioids (termed combination therapy).

Mild-to-Moderate Pain (Weak Opioids)

Weak opioids fall under the second rung of the WHO Analgesic Ladder and can be used in conjunction with the non-opioids listed above. While there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of weak opioids alone for cancer-related pain, research suggests that these medications can be effective but may be short-lived. Studies show that weak opioids often peak in effectiveness after 30-40 days in patients with cancer, and subsequently, patients end up requiring opioids [10]. Weak opioids commonly used in the U.S. include Tramadol and codeine.

- Tramadol: While data is limited on the use of Tramadol, this medication is commonly used in palliative care settings. Tramadol has both opioid and non-opioid properties and may be used if non-opioids alone are ineffective for pain control or the patient does not tolerate non-opioids [3]. Tramadol binds certain central nervous system opioid receptors (structures that sit on nerve cells and activate when coming into contact with an opioid) but is not as binding as morphine [7]. Side effects of Tramadol include dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and constipation.

- Codeine: Although recommended by the WHO for mild-to-moderate cancer-related pain, research is limited in codeine’s effectiveness as a therapy on its own. As with NSAIDs, codeine is frequently administered as part of a combination therapy. Often given in conjunction with non-opioids, it may be difficult to determine the effectiveness of codeine as a sole therapy for cancer-related pain. Codeine’s use is limited at the end-of-life due to suboptimal pain relief in some patients. Codeine is converted to morphine inside of the body which produces the analgesic effect; however, approximately 10% of the population does not have the enzyme that is needed for this conversion [21]. Side effects of codeine include nausea, vomiting, and constipation.

Moderate-to-Severe Pain (Strong Opioids)

Strong opioid medications fall under the third ladder rung of the WHO Analgesic Ladder. These medications are typically prescribed for higher levels of cancer-related pain and may be used in combination with non-opioids. The WHO recommends morphine, methadone, and fentanyl (in patch form) for cancer-related pain. Oxycodone is also a strong opioid that may be used.

- Morphine: Often the drug of choice for pain at the end-of-life, morphine works by binding with opioid receptors in the central nervous system and is metabolized in the liver and excreted through the kidneys [21]. Morphine may be administered by oral, rectal, subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous route. Oxycodone, both immediate and extended-release forms, may be used in place of oral morphine if needed (although it is 1.5 to 2 times more potent than morphine) [3]. Research suggests that in the few months and hours before death, 53%–70% of patients with cancer-related pain require a different opioid route [10]. While oral morphine has been shown to be effective with a low rate of reported intolerable adverse effects, many patients at the end-of-life require the intravenous form of morphine [10]. Morphine IV has an onset of 5-10 minutes compared to 30-60 minutes when given orally [22]. Both forms have a duration of approximately 4-6 hours.

- Methadone: Methadone is a long-acting opioid agonist used to treat pain as well as opioid use disorder. Methadone is considered an essential medication for cancer-related pain and has nearly the same analgesic potency as morphine [10]. Studies show that oral methadone can help with pain that is not relieved by other opioids, including morphine [10]. Methadone is metabolized in the liver and has a long half-life of approximately 18 hours [3]. Its use can lead to cardiac complications and life-threatening overdoses if not monitored and dosed appropriately [5, 10, 21]. Methadone should be prescribed by providers who are experienced with its use.

- Fentanyl: Fentanyl is an opioid that is 100 times stronger than morphine [23]. Fentanyl transdermal patches are recommended for long-term pain management in patients with cancer. Fentanyl patches can be worn for up to 72 hours (3 days), leading to continual absorption, and ultimately providing consistent pain relief [23]. Fentanyl remains in the system for up to 24 hours after the patch is removed due to its storage in fat (adipose tissue). Side effects include rash and redness at the site, and constipation. However, patients using the patches reported less constipation than those taking oral morphine [10, 23]. Fentanyl is typically used in patients who are opioid dependent.

Adjuvants

While unassociated with a particular pain level, adjuvant medications are also mentioned in the WHO Analgesic Ladder. Adjuvants are medications that are used in the treatment of symptoms other than pain. Adjuvants are also termed “co-analgesics,” and may be administered in conjunction with any pain medication type according to the Ladder. Adjuvants may include the following category of medications: [2]

- Antidepressants (i.e., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, duloxetine, venlafaxine)

- Anticonvulsants (i.e., gabapentin, pregabalin) – may help with nerve pain or bone metastasis pain [21]

- Topical anesthetics and therapies (e.g., Lidocaine patch, Capsaicin)

- Corticosteroids – may improve appetite or mood in the late stages of the disease [21]

- Cannabinoids

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Has an NSAID ever provided adequate pain relief for your patient who was terminally ill?

- In your facility, what is the medication of choice for patients who are terminally ill when morphine is ineffective?

- Have you found fentanyl patches to be effective for pain in patients who are terminally ill?

- In your facility, what is the most common adjuvant medication used in the care of patients who are terminally ill?

Palliative Care Safety Guidelines for Opioid Use

When hearing “opioid addiction,” patients with terminal illnesses may not be the first to come to mind. However, studies suggest that patients with cancer may be at a higher risk for opioid addiction than previously considered [5, 17].

A panel of U.S. and Canadian palliative care and addiction, and pain medicine experts came together and developed 130 safety recommendations aimed at bringing awareness to opioid use disorder among palliative care patients (North American Opioid Safety Recommendations in Adult Palliative Medicine). Of the 130 recommendations, 43 are considered high-priority and each fall under the following six domains [18].

Domain 1: General principles

- All providers (not just palliative care providers) caring for patients on palliative care should prescribe opioids as needed, including family physicians and oncologists. Palliative care providers can mentor other physicians as needed.

- Providers should not use a patient’s diagnosis or prognosis to identify whether they have an opioid use disorder.

Domain 2: Healthcare Institutions, Training, and Clinical Programs

- Healthcare facilities should monitor data regarding opioid overdoses in patients on palliative care.

- Facilities should ensure that patients have access to medications that treat opioid use disorder (for example, methadone).

- Facilities should provide mandatory training on opioid safety (for example, urine drug screening).

- Other care team members, including addiction clinicians, psy4atrists, and pain medicine clinicians should be available for consultation for patients at a high risk of opioid use disorder and overdose.

Domain 3: Patient and Caregiver Assessments

- Patients in palliative care should be assessed before receiving opioid prescriptions.

- Patients’ caregivers should be assessed for aberrant medication-taking behaviors (AMTB), which include opioid theft or borrowing, falsification of prescriptions, and route altercation (for example, injecting medications meant for oral use) [1]

- Palliative care providers should be aware that post-traumatic stress and sexual abuse can lead to AMTB.

- Providers may use the CAGE questionnaire (stands for “Cut, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye” – based on the questions asked), Opioid Risk tool, and urine drug screening to help identify patients with life-limiting illnesses who are at risk of AMTB or opioid use disorder.

Domain 4: Clinician Opioid Prescribing Practices

- Providers should have access to prescription monitoring programs to identify patients’ history of dispensed prescriptions. When the primary prescriber is away, covering providers should have access to the pain management plan and documentation.

- For patients at a high risk of AMTB, opioid use disorder, or overdose, opioids should be dispensed daily, every few days, or weekly (to avoid dispensing a large quantity at once).

- For patients with active AMTB, opioid use disorder, or a history of overdose, providers should consider consulting addiction medicine clinicians.

Domain 5: Clinician Opioid Monitoring Practices

- Patients on palliative care with AMTB, opioid use disorder, or who have overdosed (or are at a high risk of) should be assessed more frequently than patients at lower risk.

- After initiating and adjusting opioids, palliative care providers should document opioid response (medication, activity level, adverse effects, AMTB) and patients’ adherence to opioid teaching.

- Providers should include support systems (family, caregivers, etc.) in the plan of care to ensure that patients take opioids as prescribed.

- Nurses should count opioid medications in homes and clinics to monitor the amounts given.

Domain 6: Patient and Caregiver Education

- Patients with life-limiting illnesses who receive opioids (and their caregivers) should be educated on opioid use disorder, how to recognize overdose, and overall opioid safety.

- Patients should receive verbal opioid education from their prescribing provider. Consultations with pharmacists as well as other formal education could be considered.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever experienced caring for a patient with a terminal illness who also had an opioid use disorder?

- How has your experience been with family members who display aberrant medication-taking behaviors?

- Has a pain or addiction specialist ever been consulted for a patient under your care?

- What is the protocol for counting opioid medications at your facility?

Nursing Pain Assessments

The main goal in the care of patients with terminal illnesses is symptom management and improving the overall quality of life [19]. As patients near the end-of-life, comfort care and pain management take precedence. Nursing pain assessments are critical for effective pain management in patients who are terminally ill. The key focus of pain management is the continuous cycle of assessing pain, intervening with pain-relief strategies, and reevaluating pain.

Baseline Pain Assessment

First and foremost, nurses must understand the patient’s usual pain experience (or baseline) [19]. This serves as a basis for comparison to the patient’s current pain experiences.

To find out the patient’s baseline, the nurse can ask the patient or family the following questions [10, 19]:

- What is your tolerable pain level?

- Can you describe your usual pain?

- How intense is the pain on average?

- Where is your pain usually located?

- Does the pain radiate? If so, to where?

- Does the pain usually occur at certain times of the day?

- Is the pain constant or intermittent?

- What triggers or worsens the pain?

- What pain relief measures do you use? Do they help?

- What pain relief measures do not work for you?

- How often do you take medication for breakthrough pain?

- How does the pain affect your quality of life?

After a baseline has been established, nurses should plan to assess pain around the clock [21]. While continual assessments help manage pain in all patients, those with terminal illnesses are especially in need of regular assessments as their condition can progress quickly [19]. Additionally, pain in this group can take longer to alleviate if not treated early [19].

Challenges to Proper Pain Assessments

Nurses may be challenged when performing pain assessments in patients who are unable to express or verbalize their pain. In this case, nurses can ask caregivers if they believe their loved one to be in pain.

Family members are frequently around the patient and may notice that their loved one behaves in a particular way when they are in pain. This shared information can be documented in the medical record and reported to other members of the care team as needed.

Physical signs of pain may include: [19, 21]

- Vocalizations: crying, moaning

- Facial grimacing

- Excessive sweating

- Shaking or trembling

- Restlessness

- Guarding certain areas of the body

- Increased respiratory rate

- Elevated heart rate

While family pain reporting may be helpful, research suggests that this method is not ideal when patients are unresponsive, as family members often underestimate pain in this case [19]. Therefore, family reports should be used with caution and supported with other methods of determining the presence of pain, for example observing for physical signs of pain. Nurses should keep in mind that physical signs of pain simply alert the nurse that there is pain present but do not reveal details of the intensity of the pain – something that can only come from the patient [10].

On the other hand, assessing pain can be even more difficult when patients who are terminally ill have other conditions that mimic pain. While pain is often underestimated in terminally ill patients, certain conditions at the end-of-life can lead the nurse to believe that the pain is worse than it is. Severe dehydration can lead to an altered mental status and discomfort which can be misinterpreted as pain [21]. For patients who are taking long-acting opioids, dose decreases can lead to drug withdrawal, and the signs can be mistaken for pain [21].

In these cases, nurses can take a collaborative approach by consulting other members of the care team to address underlying problems and help come up with an effective pain management plan. Team members may include providers, pain specialists, fellow nurses, and the patient and their family caregivers.

Pain Assessment Tools

Pain assessment tools can be useful for nurses in the management of pain in patients who are terminally ill. Tools are available for both verbal and nonverbal patients. For patients who are responsive, verbal, and able to express their needs, nurses can use a Likert pain scale to assess pain. Likert scales grade pain based on a scale of “0 to 10” in which “0” is no pain, and “10” is the worst pain imaginable [21]. Nurses should gather more details about the pain through questioning.

For patients who are nonverbal but responsive, nurses can use a Visual Analog Scale. The Wong-Baker Faces pain scale uses images of faces with expressions in a series that indicate increasing pain. The patient can point at the face that represents the level of pain they are experiencing. Although often used in pediatric care, this scale may be useful for patients who are terminally ill and unable to speak [21].

For patients who are either unresponsive or unable to report pain in any way, observable pain assessment tools may be most beneficial. These tools assess the physical and behavioral signs of pain (as discussed earlier). Some tools may assign a pain score (or number) based on the signs observed. Documenting pain scores can make it easier to monitor a patient’s pain in the medical record.

Also, pain scores are often used for pain medication administration purposes. While this score can serve as an objective quantifier of pain, nurses should keep in mind that pain is complex in a patient who is terminally ill. Pain assessment tools should be used as a guide and should be supported with in-depth assessments and collaboration with the care team.

Examples of Pain Assessment Tools: [11, 19]

- Numeric Rating Scale (Likert)

- Faces Scale

- Behavioral Pain Scale

- Multidimensional Observation Pain Assessment Tool

- Checklist of Non-Verbal Pain Indicators

- Brief Pain Inventory

- Pain Map (provides details about the location and radiation of pain)

Examples of Specialized/Holistic Pain Assessment Tools: [11, 21]

- Palliative Outcome Scale (includes assessments of mental and social health)

- Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (includes assessments of other palliative symptoms)

- Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Is there a formalized way of assessing a patient’s baseline pain experience at your facility?

- What is the most common physical pain sign you observe in patients who are terminally ill?

- What has been your experience with family members over- or underestimating a patient’s pain?

- What is the most common pain scale used at your facility?

Nursing Pain Management Strategies

Managing pain in patients who are terminally ill is complex. Due to the nature of pain in this group, nurses should follow a holistic plan for pain management that extends beyond medication [11]. This plan should include collaborating with the interdisciplinary team, addressing all types of pain (or “total pain”), using both pharmacological and nonpharmacological methods for relief, and educating patients and families.

Nurses can create a plan of care by implementing the following interventions.

Collaborate with the Interdisciplinary Team

A multidisciplinary approach to pain management is required for the patient who is terminally ill. The plan of care should address all needs; however, nurses can’t do it alone. Interdisciplinary collaboration is the cornerstone for holistic pain management in patients at the end-of-life. Patients with advanced cancer in particular, are often polysymptomatic, and need a specialized team to manage their care [11]. A multidisciplinary approach can help to alleviate pain, provide appropriate treatments, and address underlying psychosocial distress [11].

First and foremost, nurses should collaborate with providers and clinicians to ensure the best pain control possible for patients at the end-of-life. These professionals may include prescribing physicians, pharmacists, and pain specialists. Nurses should also address the psychosocial and spiritual pain needs of patients who are terminally ill as pain is not only physical. Interdisciplinary team members can assist in screening for these needs, for example social workers. This approach has been shown to lead to patient/family satisfaction and efficacy in pain control [11]. Nurses can lead the team by performing end-of-life needs assessment (used in palliative/hospice care), setting up consultations/services as needed, serving as the main point of contact for team members, and ensuring that team members are well-informed of plan goals and progress.

Inability to get affairs in order before death, financial instability, and family conflicts may be a source of pain for patients who are terminally ill as can feelings of anger, shock, and sadness [21]. Nurses should involve any team member who has the expertise to address any needs the patient may have. These may include mental health professionals, spiritual counselors, and social workers.

Administer Opioids Around-The-Clock

Nurses should ensure that medications are administered around the clock to patients who are terminally ill. Ideally, patients on palliative care should be administered both immediate-release and sustained (or extended) release analgesia to ensure that there is pain medication in the patient’s system at all times, in other words, to “stay on top” of the pain [19]. However, the goal is to limit the use of immediate-release medications [5].

Sustained-released analgesia should be given around the clock as a basis for pain relief. Immediate-release analgesia should be provided on top of sustained-released to help manage intermittent or periodic pain that may occur, often termed breakthrough pain. Breakthrough pain can be defined as “a transitory flare of pain that occurs on a background of relatively well-controlled baseline pain” [10]. Intermittent pain may be caused by position changes and other care activities.

Monitor for Effectiveness of Opioids

Pain evaluations (or reassessments) are crucial in the management of pain in patients who are terminally ill. Nurses should perform pain evaluations at regular intervals throughout the patient’s care. Care plans should include the frequency, methods (or reassessment tools), and results of the evaluations, all of which should be documented in the patient’s medical record.

Nurses may find that a patient’s pain needs to change frequently over time. After long-term use of opioids, patients may develop “opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH)” which results in increased sensitivity to pain, and persistent pain even with dose increases [21]. OIH is often seen with the use of morphine. If OIH is observed or a patient’s pain is not well-controlled overall, nurses can recommend to the provider to switch to another opioid class or use long-acting opioids instead, like methadone or buprenorphine.

Nurses should be aware that frequent and long-term use of opioids can lead to safety risks for many patients. Therefore, nurses should develop a comprehensive plan of care that addresses both pain control and opioid safety.

Ensure Opioid Safety

While pain control is the ultimate goal for patients who are terminally ill, opioid safety should be considered as well. Safer medications (non-opioids) may be helpful in many patients who are terminally ill; however, patients with cancer may continue to require high doses of opioids regularly. Therefore, for this group, the focus should be on opioid safety (reducing the risks associated with extended use) [5].

Nurses should regularly communicate any changes in the patient’s pain needs with the provider, including possible dose adjustments, frequency changes, or medication changes. Providers need to know how often patients require opioids, their response to opioids (including adverse effects), and if pain goals are met. Nurses can also help by making recommendations for holistic pain relief strategies which may include psychological and spiritual counseling, and non-pharmacological interventions as these strategies may lead to less dependence on opioids for relief.

Consider Non-Pharmacological Interventions

While opioids are the go-to source of pain relief for many patients at the end-of-life, non-pharmacological interventions may help as well. As discussed earlier, psychosocial interventions (a type of non-pharmacological intervention) may provide some pain relief. Even something as simple as good hygiene can be helpful by preserving a patient’s dignity, which may help to alleviate psychological or spiritual pain [21]. Although some of the following interventions may not necessarily address the cancer pain directly, they may prevent further complications of pain.

Non-pharmacological pain relief strategies for patients who are terminally ill: [21]

- Proper positioning in bed (if bedridden)

- Proper oral care (to prevent painful mouth ulcerations)

- Pressure-relief equipment (to prevent painful pressure injuries)

- Acupuncture

- Biofield therapy (Reiki)

- Massage

- Music therapy

- Spiritual counseling

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- In the care of patients who are terminally ill, how do you involve family members?

- Aside from the physician, what interdisciplinary team member do you interact with most often in the care of patients who are terminally ill?

- What is one non-pharmacological intervention you implemented for a patient who was terminally ill that resulted in pain relief?

- Can you think of any additional pain relief strategies for patients who are terminally ill?

Patient and Family Education Needs

Patients and families are members of the care team and should be included in the plan of care. Nurses should arrange patient and family meetings and discuss pain needs, goals, and interventions.

Nurses, patients, and families should be on the same page regarding care. Opioid education is an integral part of pain management in patients who are terminally ill. Within the plan of care, emphasis should be placed on pharmacological education as medication will likely be the primary strategy for pain relief.

Patient/family education topics should include: [4, 18, 19, 21]

- Impact of pain on daily living

- Misconceptions about opioid use

- Medications and side effects

- Risks for opioid dependency and related overdose

- Pain-reporting and pain assessments

- Benefits of medication adherence

- Non-pharmacological therapies

Nurses can also provide education on the benefits of alternative therapies and training on how to perform many of the techniques. In the previously mentioned systematic review in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management (addressing role-playing training sessions for pain management), researchers reviewed several studies that addressed family caregiver training on therapies including massage, touch-based techniques, and reflexology.

Overall results showed a reduction in symptom severity (including pain) and an increase in the family’s confidence in using the techniques [4]. Nurses may help by either providing the education themselves (through verbal, written, or videographic means) or arranging a patient/family consultation with trained professionals for assistance.

As mentioned earlier in the course, optimal patient/family education has been proven to alleviate concerns, increase motivation and self-efficacy in managing pain, and improve pain outcomes. A proven effective strategy involves providing validation to patients and families regarding their concerns (particularly those surrounding opioid use), followed by education [19]. Nurses can help to ease any further anxiety in patients and families by clearly communicating and encouraging open discussion [3].

Conclusion

With the opioid crisis at hand, nurses still have a responsibility to ensure that pain is well-managed in patients who are terminally ill. As stated at the beginning of the course, pain is considered one of the greatest fears among patients diagnosed with terminal illnesses.

While pain may worsen as the illness progresses, several strategies may provide significant relief. Through comprehensive care plan development, interdisciplinary collaborative efforts, and the willingness to address personal fears and misconceptions about opioid use, nurses can be sure that they are providing the best care possible for patients at the end-of-life.

References + Disclaimer

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2019). Aberrant drug taking behaviors information sheet. https://sccahs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/NIDA-AberrantDrugTakingBehaviors.pdf

- Anekar, A. A., Hendrix J. M., & Cascella M. (2023). WHO Analgesic Ladder. [Updated 2023 Apr 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554435/

- Bemand-Qureshia, L., Gishen, F., & Tookman, A. (2019). Opioid use in palliative care: New developments and guidelines. Drug Review: Prescriber, 25-32. https://wchh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/psb.1755

- Chi, N. C., Barani, E., Fu, Y. K., Nakad, L., Gilbertson-White, S., Herr, K., & Saeidzadeh, S. (2020). Interventions to support family caregivers in pain management: A systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(3), 630–656.e31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.014

- Dalal, S., & Bruera, E. (2019). Pain management for patients with advanced cancer in the opioid epidemic era. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting, 39, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_100020

- Davies A. (2019). Sleep problems in advanced disease. Clinical medicine (London, England), 19(4), 302–305. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.19-4-302

- Dhesi M., Maldonado K. A., Maani C.V. (2023). Tramadol. [Updated 2023 Apr 16]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537060/

- Dydyk A. M., Jain N. K., & Gupta M. (2023). Opioid use disorder. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553166/

- Enzinger, A. C., Ghosh, K., Keating, N. L., Cutler, D. M., Landrum, M. B., & Wright, A. A. (2021). US trends in opioid access among patients with poor prognosis cancer near the end-of-life. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 39(26), 2948–2958. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.00476

- Fallon, M., Giusti, R., Aielli, F., Hoskin, P., Rolke, R., Sharma, M., Ripamonti, C. I., & ESMO Guidelines Committee. (2018). Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Annals of Oncology: Official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 29(4), iv166–iv191. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy152

- Gomes-Ferraz, C. A., Rezende, G., Fagundes, A. A., & De Carlo, M. M. R. D. P. (2022). Assessment of total pain in people in oncologic palliative care: Integrative literature review. Palliative Care and Social Practice, 16. https://doi.org/10.1177/26323524221125244

- Hadi, M. A., McHugh, G. A., & Closs, S. J. (2019). Impact of chronic pain on patients’ quality of life: A comparative mixed-methods study. Journal of Patient Experience, 6(2), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373518786013

- Hagarty, A. M., Bush, S. H., Talarico, R., Lapenskie, J., & Tanuseputro, P. (2020). Severe pain at the end-of-life: A population-level observational study. BMC Palliative Care, 19(60). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00569-2

- Ho, J. F. V., Yaakup, H., Low, G. S. H., Wong, S. L., Tho, L. M., & Tan, S. B. (2020). Morphine used for cancer pain: A strong analgesic used only at the end-of-life? A qualitative study on attitudes and perceptions of morphine in patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. Palliative Medicine, 34(5), 619–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320904905

- Illueca, M., Bradshaw, Y. S., & Carr, D. B. (2023). Spiritual pain: A symptom in search of a clinical definition. Journal of religion and health, 62(3), 1920–1932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01645-y

- International Association for the Study of Pain. (2020). IASP announces revised definition of pain. https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/iasp-news/iasp-announces-revised-definition-of-pain/

- Kurita, G. P., & Sjøgren, P. (2021). Management of cancer pain: Challenging the evidence of the recent guidelines for opioid use in palliative care. Polish Ar4ves of Internal Medicine, 131(11), 16136. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.16136

- Lau, J., Mazzotta, P., Whelan, C., Abdelaal, M., Clarke, H., Furlan, A. D., Smith, A., Husain, A., Fainsinger, R., Hui, D., Sunderji, N., & Zimmermann, C. (2022). Opioid safety recommendations in adult palliative medicine: A North American Delphi expert consensus. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 12(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003178

- Lowey, S. E. (2020). Management of severe pain in terminally ill patients at home: An evidence-based strategy. Home Healthcare Now, 38(1), 8-15. https://journals.lww.com/homehealthcarenurseonline/fulltext/2020/01000/management_of_severe_pain_in_terminally_ill.2.aspx

- Schenker, Y., Hamm, M., Bulls, H. W., Merlin, J. S., Wasilko, R., Dawdani, A., Kenkre, B., Belin, S., & Sabik, L. M. (2021). This is a different patient population: Opioid prescribing challenges for patients with cancer-related pain. JCO Oncology Practice, 17(7), e1030-e1037. https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/OP.20.01041

- Sinha A, Deshwal H, & Vashisht R. (2023). End-of-life evaluation and management of pain. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568753/

- Sobieraj D. M., Baker W. L., Martinez B. K., et al. (2019). Comparative effectiveness of analgesics to reduce acute pain in the prehospital setting. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546195/table/ch2.tab1/

- Taylor K. P., Singh K., & Goyal A. (2023). Fentanyl transdermal. [Updated 2023 Jul 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555968/

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2021). Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs). https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdmp/index.html

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2023). SUDORS dashboard: Fatal overdose data. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/fatal/dashboard/index.html

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2023). Drug basics. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/basics/

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2022). Summary of the 2022 Clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain. https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/patients/guideline.html

- Wood, J. (2019). Management of cancer pain and other symptom control. ESMO Preceptorship Supportive and Palliative Care Programme. https://oncologypro.esmo.org/content/download/187364/3401816/file/2019-Preceptorship-Supportive-Palliative-Pain-Jayne-Wood.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2023). Opioid overdose. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/opioid-overdose

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate