Course

Washington Renewal Bundle

Course Highlights

- In this Washington Renewal Bundle course, we will learn about the significance of the suicide assessment.

- You’ll also be able to work within their own organization to begin enacting change to benefit LGBTQ patients.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of a non-pharmacological treatment for patients with a history of self-harm.

About

Contact Hours Awarded:

Course By:

Kayla M. Cavicchio MSN, RN, CEN

Shane Slone DNP, RN, APRN, AGACNP-BC

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Washington Suicide Prevention Training

Introduction

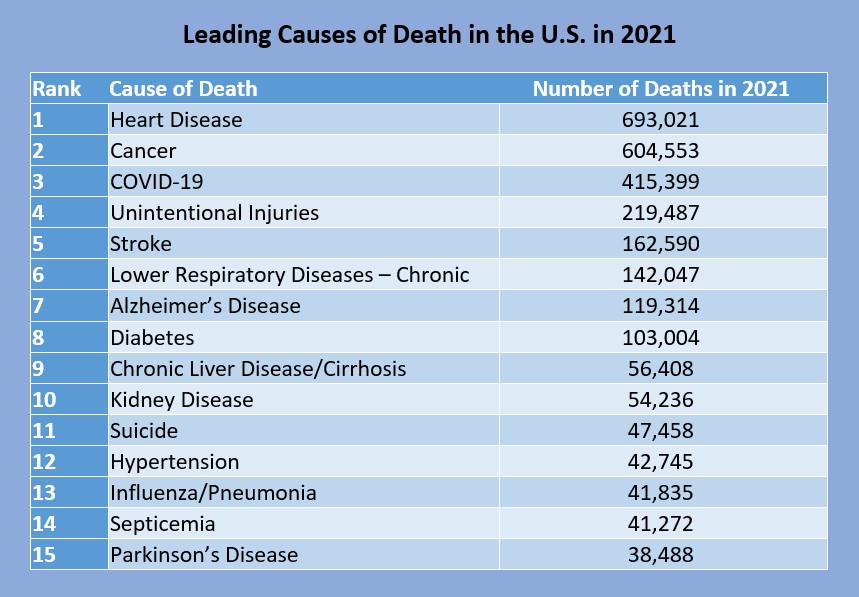

Defined as a harmful act to end one’s own life, suicide is a mental health emergency (25). In 2021, suicide claimed over 48,000 lives in the United States alone. That is approximately 130 individuals daily, and one life every 11 minutes (8). It is reported that in 2021, 12.3 million American adults considered suicide while 3.5 million made a plan, and 1.7 million made an attempt. Of those that complete suicide, 46% had a known or diagnosed mental disorder (23). In comparing this data to other medical conditions, suicide was the 11th cause of death in the United States as reflected in the chart below (5) [See figure 1].

Figure 1: Leading Causes of Death in the U.S. in 2021 (5)

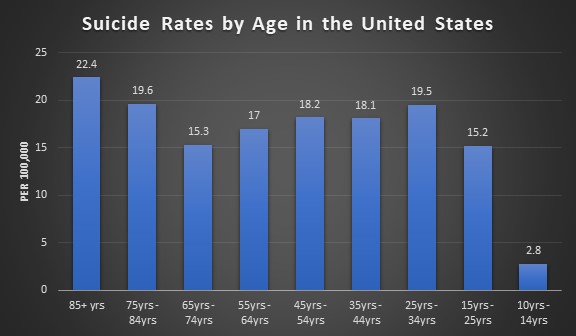

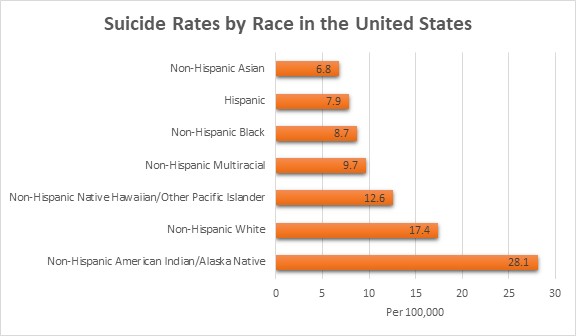

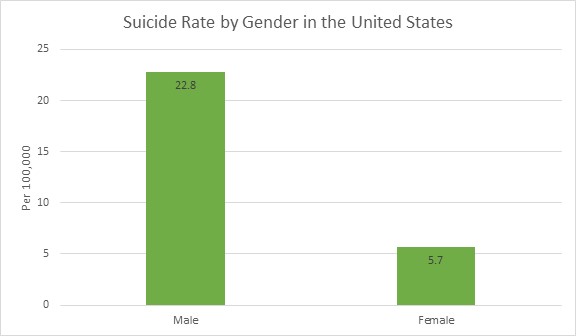

In the United States, Wyoming, Montana, and Alaska all have the highest rates of suicide, over 30 per 100,000 deaths, while New York and New Jersey have the lowest, 7.9 and 7.1 per 100,000 deaths respectively (7). Washington state ranks 27th on this list with 1,229 deaths or 15.3 in the year 2021 (7). Age wise, those 85 years and older had the highest rate of suicide in 2021 at a rate of 22.4 per 100,000. Chart 2 reflects suicide rates among Americans aged 10 to 85+ (7) [See figure 2]. Race and gender must also be considered when discussing suicide. Chart 3 discusses suicide rates based on race [See figure 3], while Chart 4 discusses rates by gender [See figure 4].

Figure 2: Suicide Rates by Age in the U.S. (7)

Figure 3: Suicide Rates by Race in the U.S. (7)

Figure 4: Suicide Rate by Gender in the U.S. (7)

Suicide is a leading cause of death on a global level with more deaths than human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/ acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), breast cancer, war, homicide, or malaria. The World Health Organization reports that an estimated 703,000 individuals die from suicide each year, approximately one in every 100 individuals. However, this number could be higher due to the COVID-19 pandemic and risk factors that were exacerbated during the pandemic: isolation, anxiety, loss of job, and financial stress (40).

Low and middle income countries see higher rates of suicide at approximately 77%. Within the past 45 years, the global suicide rate has increased 60%. For those ages 15 to 29, suicide is the fourth leading cause of death—behind road death, tuberculosis, and interpersonal violence—with it being the third leading cause of death in females and the fourth in males (40).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Looking at the data above, what can you deduce about suicide and demographics?

- What factors could lead to these numbers being incorrectly reported?

- Was there any information that you did not expect or know? Why was it surprising to you?

- Do you disagree with any of the data above? What is your rationale?

- What countries do you think have the highest rates of suicide based on the information above?

- What other information do you think is important to collect when gathering data on suicide?

Terminology

Using proper definitions to clearly understand what is being discussed is important when discussing suicide. Providers may use certain words or phrases and mean different things. By having clear definitions that are universally used, providers can understand what other providers are conveying and continue care in an appropriate manner. Below is a list of commonly used terms when referring to suicide.

| Term | Definition |

| Suicidal Ideation | Thoughts regarding killing oneself or ending one’s life. This can include planning. |

| Suicide Attempt | Non-fatal self-injurious behavior with the intent to kill oneself. |

| Suicide Intent | Intention to kill oneself by acts of suicidal behavior. |

| Suicide Behaviors | A spectrum of behaviors that ranges from planning to attempting/preparing to completing suicide. |

| Suicide | Fatal self-injurious behavior to end one’s life. |

| Suicidality | A spectrum of possible suicidal events. This does not cover if there was suicidal ideation or attempt or if the ideation or attempt is chronic or acute in nature. It is encouraged that when discussing a patient, clearly cover the actual concerns at hand. Does your patient have ideation, or did they attempt to end their life? |

| Suicide Threat | Verbalized thoughts of killing oneself through self-injurious behavior. This is to lead others to think the individual making these statements wants to die without the actual intent to do so. “If you breakup with me, I will kill myself.” |

| Suicide Gestures | Self-injurious behavior that makes others think that the individual making these gestures wants to kill themselves, despite them having no intent to. |

| Non-Suicidal Self-Injurious Thoughts | Thoughts of partaking in self-injurious behavior that includes deliberate damage to body tissue without an intent to die. |

| Non-Suicidal Self-Injury | Self-injurious behavior with deliberate damage to body tissue without an intent to die. |

| Physician-Assisted Death or Suicide; Aid in Dying; Right to Die | Passive – a provider supplying the patient with medications to take on their own to end their life Active – a provider administering the medications to the patient to end the patient’s life |

Table 1: Commonly Used Terms When Referring to Suicide (11, 21, 29)

Suicide Assessment

Healthcare providers perform a variety of assessments on their patients: cardiac assessment, respiratory assessments, neurological assessments, etc. Just as those assessments help providers decide what treatment needs to be done, the suicide assessment is utilized to evaluate a variety of factors that can increase an individual’s risk for suicide.

The latest guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association have clear goals of the suicide assessment: (17)

- Identify any psychiatric signs and symptoms

- Assess past suicidal behavior

- Review any available past treatment

- Determine if there is a family history of suicide or mental illness in the family

- Identify the patient’s current psychosocial situation and the cause of the current crisis

- Recognize strengths or coping skills and any opportunities for improvement that the patient has

With the suicide assessment, there are five areas of questions that the American Psychiatric Association discusses with examples as to what is being looked for in each area (17). These areas can be found below:

| Current Presentation of Suicidality |

|

| Psychiatric/Mental Illness |

|

| Patient History |

|

| Psychosocial Information |

|

| The Patient’s Strengths and Weaknesses |

|

Table 2: American Psychiatric Association Suicide Assessment (17)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What goals would you add to the American Psychiatric Association’s list of goals for the suicide assessment?

- Do you think these goals accurately cover suicide assessments? Why or why not?

- Which of the five categories in the suicide assessment do you think is the most important to cover? What is your rationale?

- Are there any questions you would remove or add to the list above?

- If you could create a sixth category, what would it entail?

The Interview: Gathering Information

Conducted in a private place, the suicide assessment is an interview of the patient. Providers must ensure that they ask the right questions based on information provided to them by the patient or those that are accompanying the patient. Empathy, compassion, and trust must be integrated in these interviews. Below is a list of questions that can be used during the interview process. It is important to follow your facility’s specific policies and procedures regarding the suicide assessment and use the proper screening tools. Some common screening tools utilized in healthcare will be discussed later.

| Open Ended Questions | In your life, have you ever felt as though your life was not worth living?

Have you ever wished to go to sleep and not wake up? |

| Follow Up Questions | Have you been thinking about death recently?

Has there ever been a point where you have considered harming yourself? |

| Thoughts on Suicide or Self-Harm |

|

| Previous Suicide Attempts |

|

| Repeated Suicide Attempts and Thoughts |

|

| Psychosis |

|

| Harm to Other Individuals |

|

Table 3: Suicide Assessment Interview Questions (17)

It is important to keep in mind that the answers to these questions are self-reported, so patients may not be honest for any reason. Providers should pair answers given during the interview with objective data they collect through observation and past medical records. Family, friends, and partners can be a source of information; however, providers should consider collecting information with these individuals separately.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Does your facility have a policy for suicide screening? If so, do you think the policy is effective? Why or why not?

- What methods have you found to be beneficial to asking the above questions?

- What methods are detrimental to asking the questions above?

- What specific questions do you think could be added to the above list?

- How could you rephrase the questions when talking to a family member or friend about the patient?

- What questions, when given the answer “yes”, would warrant more investigation on your part as a provider?

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale:

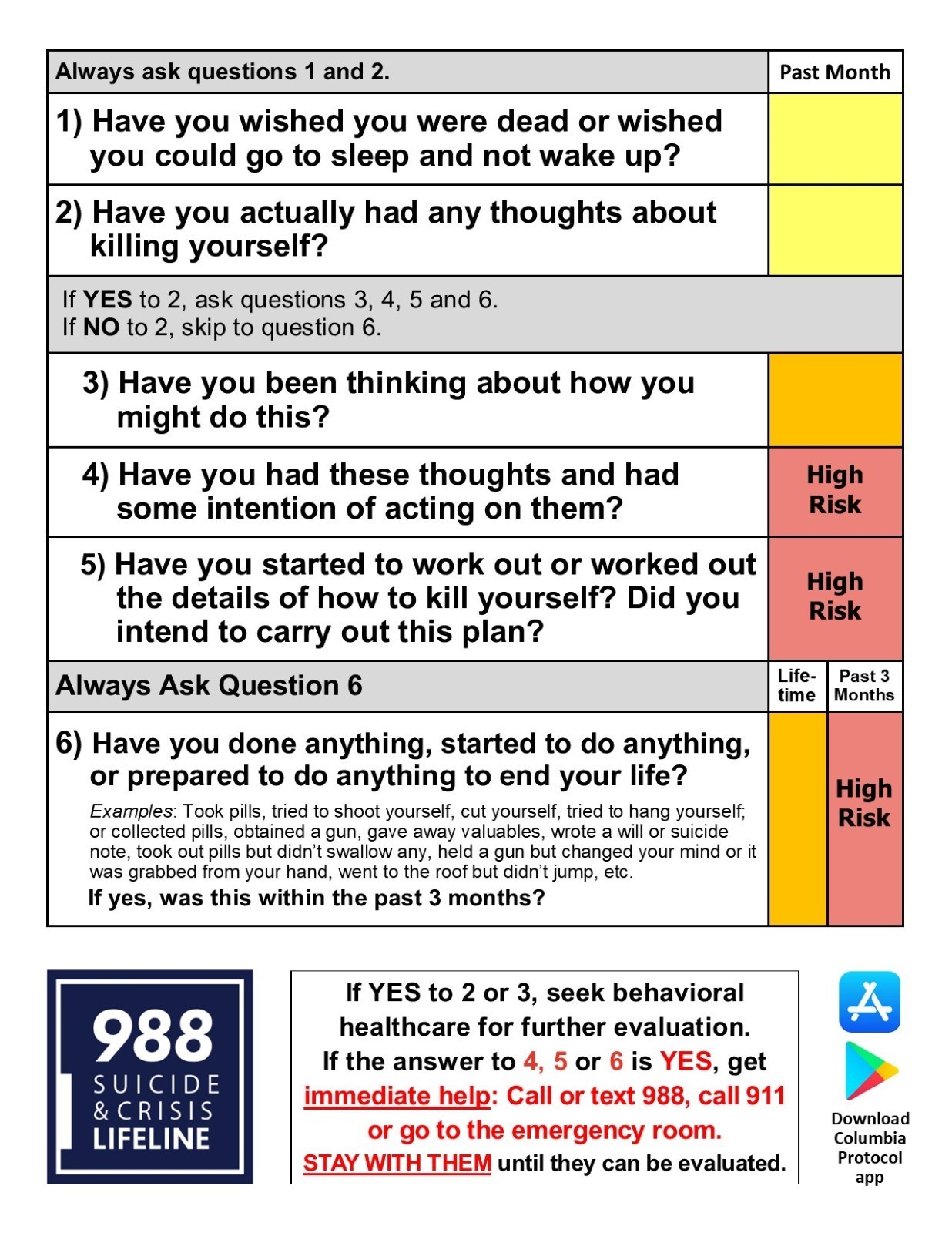

Also known as the Columbia Protocol, the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale was created by Columbia University, University of Pittsburgh, and University of Pennsylvania to be used during a 2007 National Institute of Mental Health study to decrease the suicide risk in adolescents with depression. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began using this protocol and recommending it be used in data collection in 2011. The next year, the Food and Drug Administration stated the Columbia Protocol was the standard for measuring and assessing suicidal behaviors and ideation in clinical trials (33).

The Columbia Protocol is used to assist providers and laypersons in determining if an individual is at risk for suicide. These questions are worded in plain language to ensure this scale can be administered by anyone, regardless of profession. This scale questions individuals about the following information: (33)

- If and when they have had any suicidal ideation or thoughts

- Any action they have taken to prepare for suicide and when they have done so

- If they have attempted suicide or started a suicide attempt that they interrupted or someone else did

The image below [See figure 5] is the six-question Columbia Protocol that can be used by anyone in assessing suicide risk. The far-right column is color coded based on severity if they answer “yes” to the question. Yellow is low-risk, orange is medium-risk, and red is high-risk. The answers the individual gives will guide the interventions needed. If the individual answers “yes” to questions two or three, behavioral healthcare should be sought out. If the individual answers “yes” to questions four, five, or six immediate help is needed. Those asking the questions should call the suicide and crisis lifeline, 911, or take the individual to the nearest emergency department. The individual should not be left alone until an evaluation has been done (33).

Figure 5: Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (Columbia Protocol) (33)

Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage:

The Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage consists of five questions that identifies risk and protective factors, risk levels and interventions, suicide inquiry, and documentation of treatment plans. This tool was created by Douglas Jacobs, MD, the physician who assisted in creating the suicide assessment published by the American Psychiatric Association (31). The five questions include:

- Identify risk factors with attention to those that can be modified.

- Identify protective factors and those that can be enhanced.

- Complete a suicide inquiry by asking about thoughts, plans, intent, and behavior.

- Determine risk level and any interventions that are appropriate for the risk level and attempt to reduce risk.

- Document as appropriate to include risk and rationale, interventions, and any follow-up that is needed.

The Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage can be combined with the Columbia Suicide-Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) to expand on the benefits of both tools (34).

Questions one through six from the C-SSRS all have an option for “yes” or “no,” If question two is a no, questions three through five can be skipped. After the C-SSRS questions have been asked, further assessment can be directed to precipitating events, clinical status presentation/statements, past treatment history, and any other relevant information. Providers also want to assess for access to lethal means by asking specifically about the presence of firearms in the home or how easy it would be to obtain a firearm (34).

The next step is to identify protective factors the individual has. These can be internal or external factors that the individual has that can provide support. Internal factors can consist of fear of death, or reasons for living while external factors can consist of responsibility to family or friends, supportive social network, or interacting and engaging at work and/or school (34).

Step three is the C-SSRS Suicidal Ideation Intensity screening questions that consists of thoughts, plans, and suicidal intent. Questions focus on frequency of thoughts, duration of how long the individual has had these thoughts, controlling the thoughts, if there is anything that the individual can do to deter the thoughts, and the reason for the suicidal ideation (34).

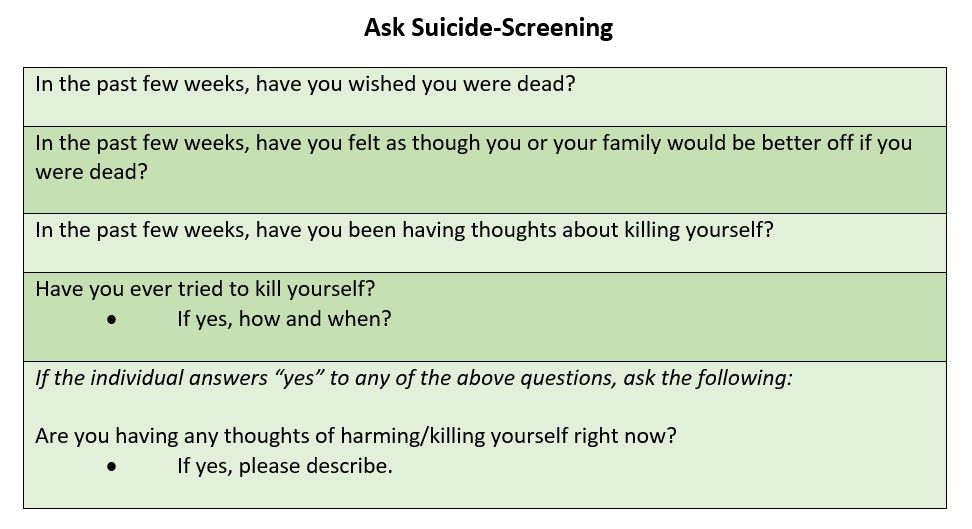

Ask Suicide-Screening Questions

The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions consists of the Suicide Risk Screening Tool that can be administered in the emergency department, inpatient medical unit, outpatient, primary care, or specialty provider offices as well as schools and juvenile detention centers. All questions are “yes” or “no” with additional open-ended questions if the individual answers “yes” (24) [See figure 6].

Figure 6: Ask Suicide-Screening (24)

The answers provided will guide treatment/interventions. If the individual answers “no” to questions one through four, no intervention is needed. If they answer “yes” to any of the questions, question five must be asked since the individual is said to have a positive screen. If question five has a “yes” response, an imminent risk is identified, or they are an acute positive screen. The patient needs a safety or full mental health evaluation before they are able to leave. Immediate interventions that must be considered are keeping the patient in eyesight at all times, removing items that could be used to harm/kill self or others, notify the provider that is responsible for the individual’s care (24).

You may wonder what to do if the individual answers “yes” to any of questions one through four but does not answer “yes” to question five. This means the individual is a non-acute positive screen and there is a potential risk identified. A brief suicide screen must be done in order to determine if a full mental health evaluation needs to be completed. The individual is not allowed to leave until they have been assessed for safety, and the provider must be notified (24).

Depending on where the individual is when asking these questions, there are some additional questions that need to be asked regarding safety and safety plans. The links below will take you to the safety screening tools based on the location of the individual being assessed (24).

Emergency Department Suicide Safety Assessment

Outpatient, Primary Care Provider, Specialty Provider Office

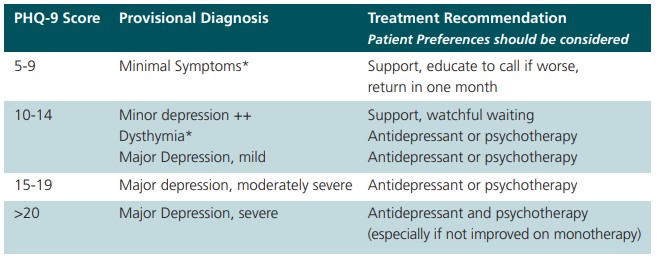

Patient Health Questionnaire

Since depression is often a risk factor for suicide, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is used to measure, screen, monitor, and diagnose depression severity. This screening utilizes diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition and rates the frequency of the individual’s symptoms. Question nine focuses on the presence and duration of suicidal thoughts while a non-scored question assigns and screens how much depression is affecting the individual’s activities of daily life and function. The minimum score is five while the maximum is 27. Anything greater than 20 has a provisional diagnosis of major/severe depression with a treatment recommendation of antidepressants and psychotherapy (27) [See figure 7]

Figure 7: Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) Results Interpretation (27)

The screening answer options include: not at all = 0, several days = 1, more than half the days = 2, and nearly every day = 3. The questions are as follows: (27)

- Little pleasure or interest in doing things

- Feeling hopeless, depressed, or down

- Difficulty sleeping, staying asleep, or sleeping too much

- Having too little energy or feeling tired

- Overeating or a poor appetite

- Feeling bad about yourself, or that your family sees you as a failure or that you have let them down

- Having difficulty concentrating on things, like reading a book or watching a movie/television

- Either being too fidgety or restless or moving/speaking slowly that you and/or others notice

- Thoughts that you would be better off dead or thoughts of hurting yourself

- Non-scored question: If you selected any of the above problems, how difficult have those problems made it for you to complete work, get along with family, friends, or manage things at home? (Answers options include: not difficult at all, somewhat difficult, very difficult, extremely difficult).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What other suicide screening or assessment tools have you seen utilized?

- Is there a specific tool you prefer? Which one and why?

- Have you heard of any up and coming assessment tools that may be more effective than the ones listed here? What is the name of the tool and what does current research show?

- Would you feel comfortable using these assessment tools on friends or family you are concerned about? Why or why not?

- If you did assess a family or friend for suicide and it was positive, how would your reactions vary than if you performed the same assessment on a patient?

Suicide Risk, Protectives Factors, and Warning Signs

Risk factors for suicide can appear in a variety of ways: individual, relationships, community, society. These are factors that increase an individual’s risk for suicide through different means. For example, stay at home orders and quarantining during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic led to isolation, which is a risk factor of suicide. Combining this with other risk factors increases the chance of an individual taking action to end their life (6).

| Characteristic | Low Risk | High Risk |

| Gender | Female | Male |

| Age | Less than 45 years old | Greater than 45 years old |

| Marital Status | Married | Widowed or divorced |

| Interpersonal Relationships | Stable | Unstable/Conflict |

| Employment | Employed | Unemployed |

| Background of Family | Low substance use, family feels healthy, they have good health | Excessive substance use, hypochondriac, chronic illness |

| Mental Health | Normal personality, social drinker, neurosis, mild depression, optimistic | Severe personality disorders, substance abuse, severe depression, hopelessness, or psychosis |

| Physical Health | Low substance use, individual feels healthy, has good health | Excessive substance use, hypochondriac, chronic illness |

| Suicidal Ideation | Low intensity, infrequent, transient | Prolonged, intense, frequent |

| Suicidal Attempt | Impulsive, first attempt, wishing for change rather than the wish to die, low lethality method, has external anger, rescue is inevitable | Multiple attempts, planned out, has a specific wish to die, is self-blaming, done with lethal methods, has a specific wish to die |

| Personal Resources Available | Controllable, has good achievement, is insightful | Has poor achievement, unstable affect, has poor insight |

| Social Resources Available | Has good rapport, they are socially integrated, has a concerned/supportive family | Are socially isolated, family is unsupportive/unresponsive, has a poor rapport |

Table 4: Criteria for Low and High Suicide Risks (3, 4)

Gender

Per research, men are four times as likely to die as a result of suicide as opposed to women. This is regardless of religion, marital status, or race. However, women are three times as likely to have thoughts of suicide and/or attempt suicide than men. Research deducts that this is because the differences in attempt methods between women and men (3). Studies show that 30% of transgender youth in the United States have attempted suicide in their lifetime while 40% of adults who identify as transgender have attempted (15).

Age

Suicide rates increase with age. Individuals who have not gone through puberty are very unlikely to attempt or die by suicide as opposed to those that have gone through puberty. Age 45 is when suicide rates are the highest among men while it is highest in women after 55. Those over the age of 65 or who are considered elderly are less likely to attempt suicide, but they are more successful when they make an attempt. As we pointed out earlier, suicide is increasing among the young population: it is the third leading cause of death among individuals aged 15-24 (3).

Marital Status

Individuals who are married and have children have a lesser likelihood than their single counterparts. Those that are single or never married have a risk two times higher than those that are married (8). Divorce suicide rates in men are three times more than women. Some individuals may attempt or die by suicide on the anniversary of a loved one’s death (3).

Sexual Orientation

Homosexual and heterosexual individuals have differences in suicide rates. Those that identify as homosexual, regardless of marital status, do have higher rates of suicide (3).

Race/Ethnicity

Caucasian individuals, regardless of gender, are three times more likely to die by suicide as opposed to African Americans. Young Alaskan Natives or Native Americans have higher than the national average rates of death by suicide (22). Moving on to immigrants, the rates are much higher than citizens of the United States (40).

Religion

Many religions have negative views on suicide. Despite that, religious groups such as Protestants and Jews have higher rates of suicide than Muslim and Catholics combined. It is important to note that religion alone is not an accurate indicator of suicide, but the inclusion and societal integration and beliefs are better predictive factors (3).

Occupation

Increases in socioeconomic status increase the risk of suicide in any individual. It is noted that being employed is one protective factor, and while true, there are some occupations that increase the risk. Lawyers, healthcare providers, mechanics, artists, and insurance agents are classified as high-risk occupations. On the other hand, unemployment brings an increased risk of suicide in comparison to those that are employed. Providers should be aware that suicide risk increases during economic depressions and decreases during economic booms (3).

Physical Health

Good physical health is vital to good mental health and wellbeing as poor physical health contributes to at least half of all suicides. Thirty percent of those who died by suicide saw a provider within the past six months prior. Physical effects that increase risk factors include disfigurement, loss of mobility, and chronic pain. If these effects impact the individual’s relationships and/or work life, that can increase suicide risk even more (3).

Mental Health

Almost 95% of those who die by suicide have at least one diagnosed mental health disorder. Depressive disorders like major depressive disorder account for 80% of all suicides, and a diagnosis of delusional depression comes with the highest risk of suicide. Those with schizophrenia have a 10% risk, while those with delirium or dementia have a 5% risk of suicide. Alcohol dependency is found in over one fourth of suicide cases (3).

Substance Abuse

As mentioned earlier, alcohol or other substances can play a large factor in suicide. The use of any substance can lead to impairment of judgement, sedation, or manic behavior that can lead to respiratory depression or self-injury (19).

If there is a suspicion of substance abuse, it is important to consider discussing these concerns with patients in a non-threatening, non-judgmental manner (19). Providers should start with questions regarding socially acceptable habits: exercise or dieting, caffeine, and tobacco can help ease the patient into comfort. This is something that should be done as standard procedure for all patients, and providers can even say that to patients. “We ask these questions to everyone.” Providers need to ask questions such as “how many”, “how much”, “how often” to any “yes” answer the patient provides (37). Below are common substances that are abused:

- Alcohol: While alcohol is legal to consume for those over the age of 21 in the United States, patients may still be hesitant to answer truthfully. Providers must take patients at their word but make note of any objective data that they gather through their assessment. Appearances of patients who may have a substance abuse disorder will be discussed later. It is important to ask about specific alcoholic beverages as some cultures may not consider beer or wine to be alcohol (37).

- Over-the-counter medications: These medications can be a source of intentional or unintentional substance abuse, so providers must ensure that they are asking about herbal supplements, cold and cough medications, or diet aids. Prescription medications might be prescribed to the patient or someone else and usually consists of sleeping aids, pain medications, diet medications, or attention deficit (hyperactive) disorder medications (37).

- Cannabis/Marijuana: Cannabis or marijuana use has various levels of legality in states across the United States, so providers should be aware of their state’s rules and regulations regarding its use. Regardless, it is important to screen for usage during any patient interaction as treatments can be affected (37).

- Illicit Drugs: Illicit or street drugs consist of cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, inhalants, hallucinogens, and more. Asking about use of the substances is important, and again should be done in a non-judgmental manner. Methods include saying the name of each substance as opposed to calling them illegal or street drugs are a great way of doing this. Providers need to assess the amount, method of usage, if patients are doing these substances with someone who they consider safe, if they have access to Narcan, if they are buying from the same person, and if they are sharing needles, or using dirty or clean needles (37).

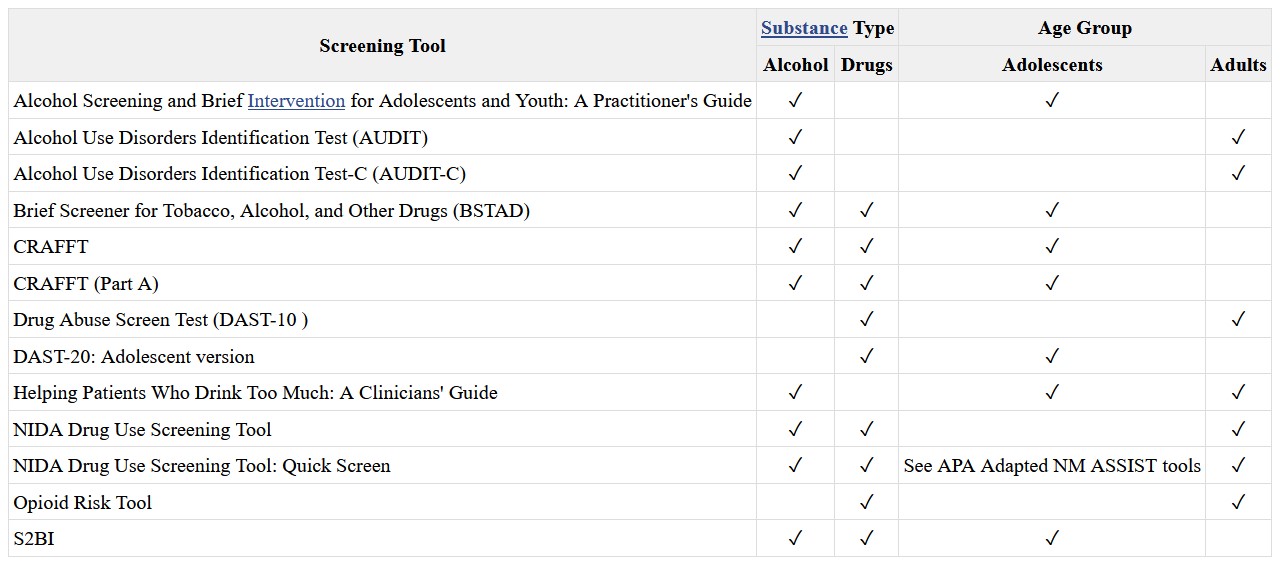

Knowing the patient’s own view of their substance use can be very helpful. If the patient does not see their usage as a problem or reason for concern, they are less likely to seek out help or accept it. The same goes for consequences (19). Below is a table of tools providers can use to screen for substance abuse in adults and adolescents (32) [See figure 8].

Figure 8: List of Substance Abuse Screening Tools for Adults and Adolescents (32)

As mentioned above, patients may not be completely honest when providing substance use history. Providers need to collect both subjective and objective data to assist them in providing the proper care.

Patients may vocalize thoughts of continuously thinking about the substance they are using. They might forget things or have a hard time focusing or concentrating. If they are aware or know they are abusing a substance, they may be unable to stop regardless of a physical and/or mental challenge that is a result of the substance (19).

There may be reports of strong cravings to use the substance. Patients may report a desire to decrease use of the substance, stop using it all together, or they may take actions to obtain the substance that leaves them feeling guilty or remorseful. Depending on the substance used, the patient may report changes in mood or mood swings (19).

Behaviors may vary from patient to patient, and the type of substance they are using. They may dedicate extensive amounts of time to obtain the substance, neglect important tasks or individuals within their lives, or actively appear intoxicated. They may argue or get in trouble with family, friends, or law enforcement. They may take the substance when it is hazardous to the health and safety of themselves and others. They may also start taking the substance in higher doses for longer than recommended (19).

The physical appearance of the patient can consist of noticeable changes in weight, bloodshot eyes, increased tolerance for a particular substance, constricted or dilated pupils, or irregular sleep patterns. Patients may also have signs of withdrawal that consist of shakiness, sweating, agitation, headaches, nausea and/or vomiting, fatigue, and possibly seizures (19).

Stigma

Stigma is known as negative thoughts that are held towards other individuals, groups, or circumstances (19, 30). Usually stigma stems from differences. Differences can encompass any part of life, ranging from clothing to gender to race to medical or mental health diagnoses. Stigma impacts how society addresses those differences. If most of society sees mental health and suicide as shameful, those that have mental health diagnoses or have attempted/thought of suicide may be less likely to seek help—this is social stigma. Those with mental health diagnoses may have self or perceived stigma. These individuals internalize society’s opinions or their own perception of discrimination (30).

Traumatic Childhood

Traumatic childhood events such as sexual abuse are directly linked to increased risks of suicide or suicide attempts. It is vital that healthcare providers assess children and adults for this history to assist with appropriate treatment and support in order to decrease risks and guide the individual to recovery (19).

Genetics

Recent studies have discovered a locus in the form of a DNA variation on chromosome seven that can increase an individual’s risk for suicide. Other variations in this region can lead to risk-taking behaviors, smoking, and insomnia. This variation was present even after “conditioning on major depressive disorder.” The locus has been deemed to be independent from psychiatric diagnoses as well, meaning that those without a mental health disorder could still be at risk for suicide attempts or suicide if this variation is present (22).

General/Other Risk Factors

There are other general risk factors that can impact an individual and their risk for suicide. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention rank these risks from individual risk factors to societal risk factors and describes them: (6)

- Individual Risk Factors: serious or chronic illness such as chronic pain, previous attempts of suicide, criminal and/or legal problems, substance use, history of mental illnesses like depression, feelings of hopelessness, job or financial loss or problems, current and/or prior history of adverse childhood experiences, and victim of violence or perpetration.

- Relationship Risk Factors: family or loved one having a history of suicide, social isolation, loss of relationship, bullying, and violent or high-conflict relationships.

- Community Risk Factors: stress of acculturation, historical trauma, violence in the community, discrimination, lack of access to healthcare, and cluster of suicide within the community.

- Society Risk Factors: stigma regarding seeking help for mental health or mental illness, unsafe/inaccurate medical portrayal of suicide/self-harm, and access to lethal means in populations at risk for suicide.

Protective factors are those that improve mental health and provide support to the individual. These can range from individual to societal levels of protection. It is important to know that everyone can participate in preventing suicide within their relationships, communities, or society through equal support (6). Below are some protective factors: (6)

- Individual Protective Factors: strong sense of culture, reasons for living (like friends, family, pets, etc.), effective coping skills, and effective problem-solving skills.

- Relationship Protective Factors: partner, family, and friend support, and having or feeling a connection to others.

- Community Protective Factors: feeling a connection to school, work, or community, and having consistent and high-quality mental and physical healthcare.

- Society Protective Factors: reducing the access and availability of lethal means to those that are at a higher risk of suicide, and religious, moral, or cultural objection to suicide and/or suicide attempts.

Case Study Reflection

Below is a case study divided into three parts. This case study will take you through a scenario and ask questions about what should or should not be done with this patient based on the information that has been covered so far (6).

Case Study Reflection 1

Noelle has lived in your neighborhood for years and is one of your favorite neighbors. She would sometimes watch your children when they were young and worked as a waitress until she retired recently. She mentioned to you once, shortly after her retirement, that her funds are “not what they used to be” as she is relying on her social security’s fixed income. This forces her to budget more than she ever needed to, and she is contemplating finding a job. However, her knee pain has been getting worse, keeping her from moving around and sleeping. You notice she doesn’t garden like she used to. One day when you stop by, you ask her about her children, who you have not seen visit. She tells you they are busy, but she would like to see them because she is lonely. She appears restless and sullen.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some of the factors that put Noelle at an increased risk for suicide?

- What follow-up questions could you ask her?

- Is there anything concerning you at this moment? Why or why not?

- Would you want to use any of the suicide assessment tools listed in the course at this time? What is your rationale?

- What are your next steps to help Noelle and possibly decrease her risk of suicide?

A few days later, you realize you have not seen Noelle outside of her house, nor have you seen her two dogs. Since you know her children, you call the older son to reach out and see if he has spoken with his mother. The son sounds rushed on the phone and says they only talked for a few minutes the day before. Deciding to call Noelle yourself, you are surprised that she answers the phone. She again reiterates that it is hard for her to move and leave the house because of her knees and age. She says that she is lonely. You state you would like to check on her every day for a few days, but she adamantly declines. “I just get irritable around people,” she tells you.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Would you say that Noelle is better or worse than before? What evidence do you have to support your answer?

- How could you intervene to offer Noelle support?

- Who else could you get involved with when it comes to ensuring Noelle’s safety?

- Would you like to perform a suicide risk assessment on Noelle? Which one would you use?

- Do you think Noelle needs to be assessed by a trained professional? If yes, what provider do you think would be helpful?

The day after your conversation with Noelle, you go to check on her as you are still concerned. When you knock on the door, no one answers, but you know someone is home because of the noises coming from the house. You are able to enter her house through the patio, something she had given you permission to do in the past, and you can now hear her dogs barking continuously. After calling for Noelle and not receiving an answer, you head upstairs to her room. You find Noelle in bed with an empty bottle of prescribed pain medication that she uses for her knees. She seems to be “out of it” but is crying and muttering that she “can’t do this anymore.”

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is your first priority with providing care for Noelle?

- What information should you provide to first responders when they arrive on scene?

- Looking back on the situation, is there anything that could have been done differently by all parties involved to prevent Noelle from getting to the point where she attempted to take her life?

- What can you and your other neighbors do for Noelle while she is being evaluated?

- Are there any support methods you can offer Noelle when she returns home?

Non-Suicidal Self-Injury

As discussed earlier, self-injury can either be non-suicidal or suicidal in nature. Those who perform non-suicidal self-injury are not looking to end their lives, but instead are trying to escape emotions, thoughts, or other feelings that are causing distress (i.e., not being good enough; feeling anguish, despair, desperate, or depressed; needing a way to relieve stress; believing that people do not care). Physical pain is created through a variety of means, including cutting, burning, biting, scratching, pulling out hair, kicking or punching objects to injure self, or snapping rubber bands on their bodies (19).

To determine if the injury is related to a suicide attempt or not, providers must perform a suicide assessment and discuss actions and behaviors with the patient in a non-judgmental manner. It is important to remember that non-suicidal self-injury is a coping mechanism for individuals, and it may be the last coping mechanism available before an individual makes a suicide attempt. Providers need to refrain from preventing self-injurious behavior until they provide the patient with other coping mechanisms. Always follow facility policy and procedures when addressing non-suicidal self-injury (19).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What methods of non-suicidal self-injury have you seen individuals use?

- How did you assist these patients in gaining better coping skills?

- What barriers did you face?

- Were there any successes in helping the patient(s) gain better coping skills?

- What recommendations would you give others trying to help their patients refrain from non-suicidal self-injury?

- Are there any reasons you think someone would not want to stop their behavior?

Understanding the Risk of Suicide: Using Assessment Information

As discussed, suicide has many risk factors, one of which is past suicide attempts. Studies have shown this correlation to be more serious than previously thought, with higher rates of a second attempt within the first three months of the first attempt. What does this mean? As providers we should be providing more support during that initial post-attempt phase to ensure patients have better coping skills and resources to decrease the chances of another attempt.

The provider must look at a variety of factors gained during the suicide assessment interview such as any previous self-harming behaviors, suicide attempts, and/or aborted attempts (stopped by themselves or someone else). If you are not the patient’s regular provider, consider consulting their primary care provider or psychiatric provider to assess past history of suicide (3).

Previous hospitalizations for suicide attempts and/or past psychiatric treatment provides important information to the provider that they should be aware of. Consulting with the patient, family, or friends can provide valuable insight into the patient’s history and coping skills (3). Patients may have a history of agitation, anxiety, depression, feelings of hopelessness, changes in mood (which can be severe), insomnia, or substance use (19).

Family history and dynamics can impact a patient and be a factor for suicide, either a risk or preventative. Dysfunctions within the family have a direct link to suicide and self-injurious behaviors. Providers should ask about family history regarding mental health and illnesses as well as family dynamics. Separations, family history of substance abuse, legal or financial trouble, abuse, or domestic violence should be documented and reported as required by law (3).

Assessing the patient’s presentation at the time of the interview is vital and can provide significant objective data on the patient’s psychological status. Providers should ask questions about current stressors in their lives: financial hardships, interpersonal loss, or changes in their economic status. As already discussed, loss of job or residence, family dynamics, religious beliefs, and cultural customs can impact the patient as well (3).

Determining strengths and areas for improvement will guide the provider in providing support, treatment, and referrals as care progresses. These traits may include coping skills, support (from family, friends, religion, or community), personality, and methods of thinking or solving problems. It is important that patients are guided to adjust their thought processes, such as mentalities and self-expectations, that can be detrimental to mental health (3).

Case Study Reflection 2

Marc is a new patient at your organization, who recently relocated to Washington from Wisconsin for a new job. He has moved to your city with his wife and young children. While talking with Marc, you can tell that the move has not been easy on him while his family seems to be settling in well. He makes a comment about “feeling inadequate at work” because everyone has expectations for him despite the fact that he is new to the company and role. He reports that he does not feel a sense of community where he lives, saying that the city he came from was much friendlier and warmer.

You note that Marc does not mention any current coping skills, but you do identify that he used to bike-ride to de-stress after work. The environment is different for him, and he has different work hours with the new position, making it challenging for him to find time or energy to bike. Marc says he thinks that relocating was not the right decision for his family as he has barely any time for them and less time for himself. He says he is a failure.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is your priority when assessing Marc? What is your rationale for that decision?

- Are there any additional questions you would like to ask Marc?

- What are some of Marc’s strengths?

- What areas for improvement do you see in Marc?

- What are at least three coping mechanisms that Marc can use or develop to assist him during this transition?

- What are other coping strategies that Marc could develop?

Suicide Risk: Documentation

Documentation of the patient’s suicide assessment is a vital part of the provider’s job. Based on the hospital or facility’s policies, providers might document a suicide risk assessment each time they encounter the patient. Ensure that you are following proper policies and procedures regarding when a suicide risk assessment should be documented. Some best practices include documenting during the first inpatient hospitalization or the initial psychiatric assessment, when there is a significant change, and when there is an occurrence of suicidal ideation or behavior (3).

Providers should consider documenting the following: (3)

- Any changes in treatment

- Risk assessments

- Prescription medications

- Previous treatments, especially regarding past suicide attempts

- Decision making processes

- Conversations with other providers

- The patient’s access to firearms

Actions and Referrals for the Various Levels of Suicide Risk

Patient statements and actions guide the actions and steps a healthcare provider must take. If a patient has attempted suicide, admission to a hospital to treat any medical injuries is the first step, followed by admission to an inpatient behavioral health unit or hospital. Some facilities may have psychiatrists or clinical psychologists see the patient when they are on the medical floor, so both types of treatments can occur simultaneously. Individuals who may benefit from an inpatient psychiatric admission include those who have acute suicidal ideation with previous attempts, previous suicide attempts with no suicidal ideation (but has other psychiatric concerns), or an exacerbation of a mental illness. Individuals who would benefit from outpatient services include those with suicidal ideation or strong support systems (3).

| Treatment | Characteristics |

| Inpatient Treatment – Required | After an aborted suicide attempt or suicide attempt if:

|

| Inpatient Treatment – Might be Considered | If there is a presence of suicidal ideation along with:

|

| Outpatient Treatment – Recommendation | Post suicide attempt, or the patient has suicidal ideation or a plan:

|

Table 5: Suicide Attempt Criteria for Recommended Treatment Services (3)

While some patients may agree to inpatient treatment after a suicide attempt, others may not. The state of Washington has an Involuntary Treatment Act that manages the psychiatric hold. For additional information, review Title 71.05 of the Revised Code of Washington (39).

Per Washington legislation, any individual that has firsthand knowledge of an individual they are concerned about can refer them for an evaluation that must be completed by a trained professional such as a psychiatric nurse practitioner or a psychiatrist. The following two points meet the criteria for involuntary admission: (39)

- The individual must have a diagnosed or diagnosable mental health disorder. This is defined as an organic, emotional, or mental impairment that severely impacts the individual’s volitional or cognitive behavior.

- They present with harm to others, property, or self, or the patient is classified as gravely disabled (unable to care for themselves safely).

The trained mental health provider can make a determination if the patient meets the criteria, and if they do, they can initiate a 72-hour involuntary hold. After this hold is initiated, the patient will be transferred to a psychiatric hospital or receiving facility to receive the appropriate treatment. It is important to remember that patients under these holds still maintain their individual rights while in the facility and are presumed competent. This places the patient in a confidential status (39).

Once the 72 hours have passed, the patient can request legal counsel and be evaluated by the court if they continue to refuse voluntary treatment. Psychologists typically evaluate the patients by performing independent exams to determine if the patient still meets the criteria for involuntary placement. The patient and the legal counsel (who is representing the patient) will meet and discuss the patient’s desires in a Probable Cause Hearing (39).

In this meeting, the judge will determine if there is probable cause for the patient to continue treatment on an involuntary placement. During the hearing, the following four decisions can be made (39):

- Involuntary petition is dropped, and the patient is released.

- The case is dismissed by the judge, resulting in the patient being released.

- The patient can make the decision to stay voluntarily.

- The patient can be ordered by the judge to continue involuntarily placement and can stay at the facility for 14 additional days.

If a patient is ordered to stay at the facility for 14 additional days and the provider believes that additional treatment longer than 14 days is needed, a 90-day petition can be filed. This will lead to another hearing where the judge can agree or disagree with the petition. An agreement of the petition would lead to the patient being transferred to the Western State Hospital for adults or the Fairfax Hospital for children (39).

Case Study Reflection 3

Jack is a 19-year-old teenager who has just been admitted to your unit following an overdose of prescription medications. It is unclear from the emergency department notes if his actions were accidental or not, and today is your first day speaking with him. He tells you that he was in a car accident last year and has been having a hard time ever since. Past medical history reports depression and feelings of hopelessness. When you ask him about what brought him to your facility, he admits to you that he was trying to end his life. Jake tells you he has seen a provider in the past but does not feel like they listened to him.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Who should you notify regarding the information that the patient disclosed to you?

- What precautions do you think you should take?

- How can you help Jake during his time on your unit?

- What type of treatment do you think Jake needs after he has been cleared medically?

- Do you think Jake will agree to further treatment? What is the rationale?

- If Jake does not agree to treatment, what would be the next steps? What if he does agree to treatment?

Management and Treatment

Within any healthcare setting, the provider and patient must develop a therapeutic rapport or alliance to ensure that the relationship is productive and respectful. Trust should be a key factor in these relationships. If the patient cannot trust the provider, then they may not wish to disclose personal information that could aid the provider in treatments and care. The opposite can be true as well (17).

Patient safety must be a concern at all times during the provider/patient relationship. If there is concern for the safety of the patient at any time, the proper assessments should be performed, and professional staff should be notified (17).

Together with the patient, the provider needs to create an effective treatment plan for the patient with a focus on the treatment setting, proper education for the patient and their family or other support, and care coordination with other providers. Treatment should be the most beneficial but least restrictive (17).

Non-Pharmacological Interventions and Treatments

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The Department of Veteran Affairs recommends the use of suicide-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with patients who have a recent history of self-harm or injury (35). Overall, this type of treatment can be beneficial for patients with diagnoses including anxiety disorders, depression, eating disorders, severe mental illness, alcohol and other substance abuse disorders, and even martial problems. The basis for CBT is built on the following three core principles: (2)

- Psychological behaviors can be a result of learned patterns of negative behavior

- Psychological behaviors can be a result of unhelpful ways of thinking

- Those who have psychological diagnoses can learn and develop better coping mechanisms that may help in being more effective in daily life and relieving the symptoms they are experiencing.

Changes in thinking patterns can be attained by training individuals to recognize alterations in their thinking that might create problems in their life. Changes can also occur when the training focuses on reframing an individual’s thinking, which may occur through reevaluating the thoughts realistically rather than based on negativity. Patients can look into obtaining a better understanding of how others are motivated or behave. Problem solving skills can be taught or expanded to help patients cope. Providers can promote role play (to prepare for particular situations), teach patients mind and body relaxation techniques, or encourage patients to face fears rather than avoid them. Patients and providers can work together to come up with the best method to implement CBT (2).

Dialect Behavioral Therapy

Those with recent self-injury or harm as well as borderline personality disorders can benefit from dialect behavior therapy (DBT) (35). It can also be used for those with depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder. A type of talk therapy, DBT helps patients accept the reality of their lives and behaviors with the goal to help change the unhelpful behaviors and ultimately change their lives. This is beneficial in many conditions as it focuses on addressing the negative coping skills used to manage negative emotions. Patients may participate one-on-one with the provider, or they may enter DBT group therapy to advance skills gained in one-on-one sessions (10).

Other Psychotherapies

Interpersonal Therapy – helps patients understand interpersonal problems such as conflicts with family or friends, difficulty relating to others, unresolved grief, and changes in work or social roles. This type of therapy assists patients to learn healthier ways to cope and express themselves through effective communication (3).

Psychodynamic Therapy – used with adults to reflect on childhood and other past experiences in order to bring to light some emotions, feelings, thoughts that may have been suppressed. Patients may have developed patterns that can be deemed unhealthy, and this type of therapy can help change those unhealthy coping strategies. Psychoanalysis is a more in-depth form of psychodynamic therapy that is held several times a week (3).

Supportive Therapy – used to support patients in developing their own coping strategies and resources. This process can be used to build self-esteem, improve community and social interactions, and reduce anxiety (3).

Pet, Play, and Creative Art Therapy – can be used in combination with any of the above therapies.

Case Study Reflection 4

Sabrina and her mother come to your outpatient facility for a routine medical visit. Sabrina started high school and wants to join the lacrosse team, so she needs a physical in order to participate. During your assessment you notice that she has lost a significant amount of weight. When her mother steps out of the room, you ask her how she is doing. Sabrina reports that she has been in the nurse’s office more often with stomachaches and nausea. She also reports she fainted in class but was able to convince the school to not call her mother. She tells you that she would like to talk to her mother about all of the stress with school she is experiencing though she is not sure how.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What would you initially diagnose Sabrina with? Provide your rationale.

- How could you discuss your concerns with Sabrina in a non-judgmental way?

- Are you concerned for Sabrina? Would you screen her for suicide ideation at this time?

- Are you obligated to disclose the information you gathered to her mother? Why or why not?

- Since Sabrina wants to talk to her mother about her worries and stress, how can you facilitate a conversation between them?

- What types of psychotherapy would you recommend to Sabrina?

Medical Treatments and Interventions

Providers need to be aware of medications that can cause or exacerbate depression in patients and increase the risk of suicide. While the list is not all inclusive, some common medications include calcium channel blockers, sedatives, corticosteroids, beta-blockers, H2 blockers, and chemotherapy agents. After a suicide attempt, the provider should assess all medications and diagnoses the patient has. From there, the providers should decide if adjustments should be made (3).

As discussed previously, depression is a major factor in suicide and is present in many other medical and mental health conditions. Anxiety (includes general phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety, obsessive compulsive, social anxiety, agoraphobia without panic, and panic disorder), trauma/stress related disorders, bipolar disorder, psychosis, eating disorders, substance use disorders, and non-suicidal self-injury can all have depression as a symptom (19). Medical conditions that co-exist with or exacerbate depression consist of cancer, heart disease, dementia, diabetes, Parkinson’s Disease, and stroke (3).

Medication

The goal of medication administration is to assist the patient to regain balance in their brain’s chemistry and restore it to optimal functioning by controlling the signs and symptoms the patient may have. These medications do not usually result in a cure; instead, they should be taken for extended periods of time, possibly for the patient’s lifetime. These medications can also be combined with other treatment options to give the patient the best possible outcomes (3).

Controversy exists with patients taking antidepressants. In 2004, the Food and Drug Administration made the decision to require that antidepressants have a black box warning addressing increased risks of suicide in young adults. There was a similar claim regarding antiepileptic medications, but the black box warning was not required due to the scientific advisory committee voting against it. Regardless, providers need to stay up to date on medications and warnings, ensuring that they are administering medications in the best interest of their patients. One medication that may work for one patient may not work for another (13).

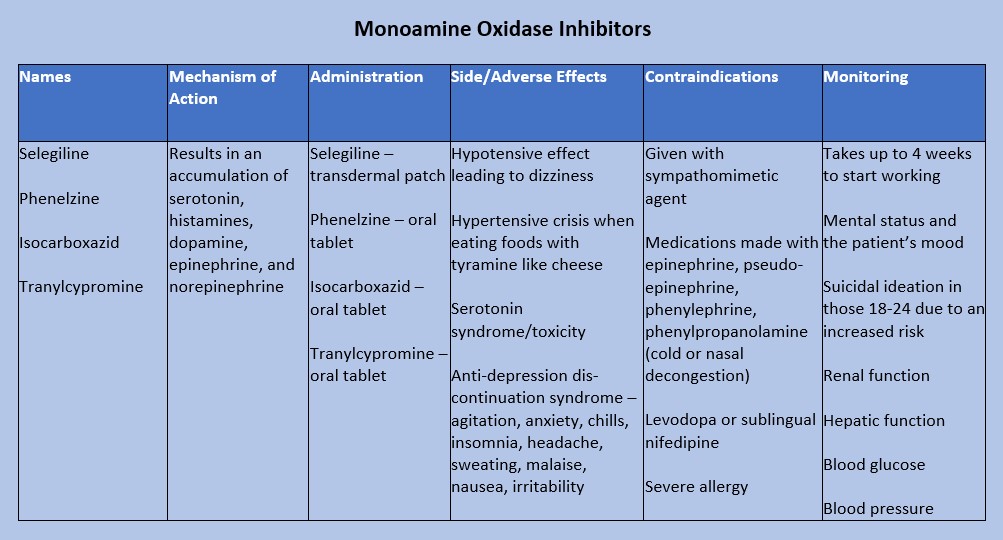

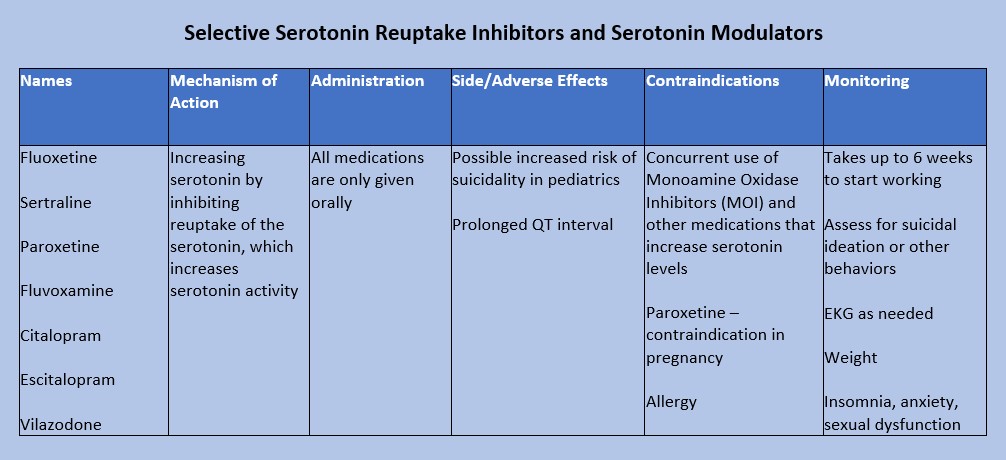

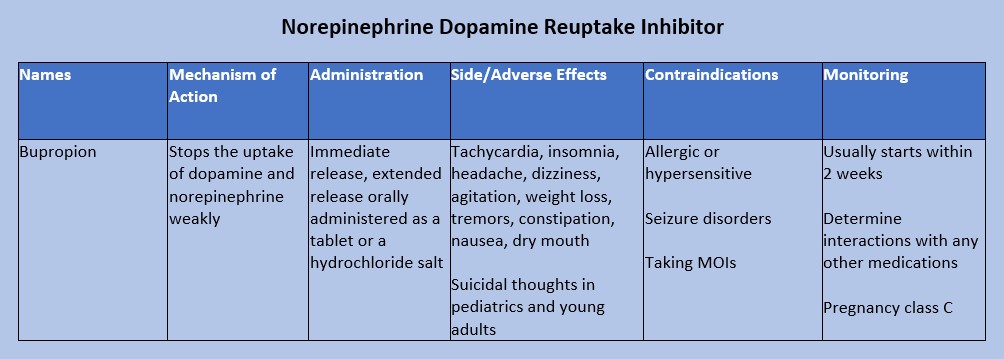

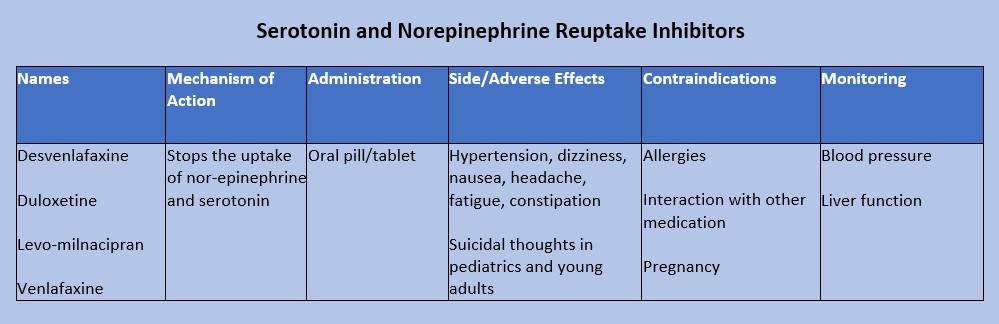

Antidepressants come in several categories that are based on the type of brain chemical (dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin). These categories include serotonin modulators, norepinephrine dopamine reuptake inhibitor, monoamine oxidase inhibitor, tricyclic agents, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Figure 9: Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (28)

Figure 10: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Serotonin Modulators (9)

Figure 11: Norepinephrine Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor (16)

Figure 12: Serotonin and nor-epinephrine reuptake inhibitors (18)

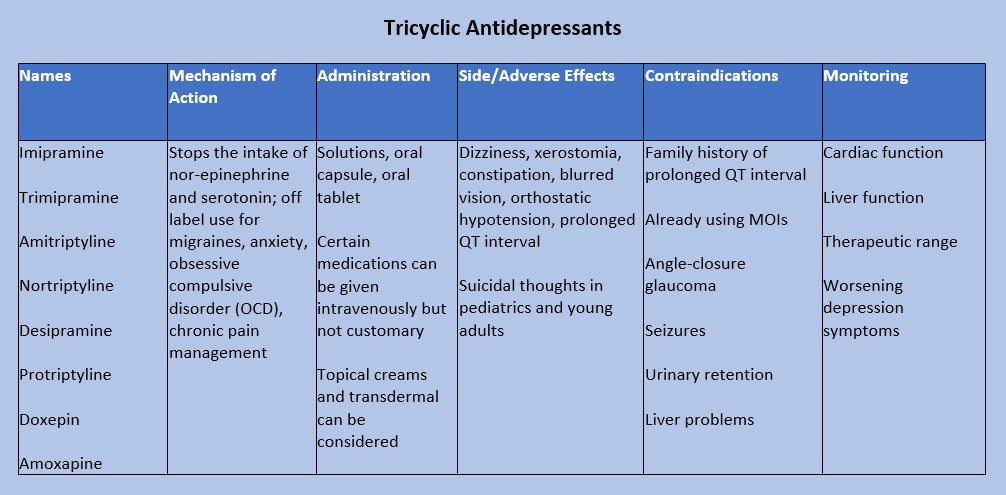

Figure 13: Tricyclic Antidepressants (20)

Case Study Reflection 5

Hope is a 35-year-old who recently moved to your town with her husband, Douglas. She is a teacher at the nearby elementary school while Douglas works in a tech startup, but he was suddenly laid off from his job. After this, Hope brings him to your facility to be evaluated. She tells you that Douglas has become increasingly agitated. He told her that he is a failure and “did not make the right choices in my life.” Douglas admits to drinking heavily with friends since he was laid off.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What questions do you need to ask Douglas regarding his mental health?

- Is there any medication or medication group that you would recommend prescribed to Douglas?

- If Douglas was prescribed the medication you recommended, what would you teach him about medication administration and adverse effects?

- How would you educate his wife Hope on adverse effects?

- Which adverse effects should prompt Douglas to see a provider?

- If Douglas called your facility with reports of itchiness, a rash, and swelling, what would you instruct him to do?

Substance Abuse Care

Research shows that the longer substance abuse goes on, the harder it is to recover from. Early recognition and treatment can decrease the chance of serious medical conditions or death (19). There are multiple treatment options for patients with substance use disorders, but providers must be aware of each patient’s individual circumstances: time, family and friend support, cost/expenses, and willingness.

All individuals go through the five stages of change when they want to make adjustments in their lives. Those with substance abuse disorders must be willing to make a change for themselves. Even though a person with a substance abuse disorder may want to change for another person or situation (changing for grandchildren, a spouse/romantic partner, children, etc.), they must consider that this person/situation may not remain in their lives. For this reason, they must be willing to make a change for themselves. Sometimes family or friends become too overburdened with the individual’s substance abuse, driving them away. That could inhibit or completely stop the person’s desire to change. The patient may say, “they’re no longer around, what’s the point?” Providers should not deter patients from having support systems as these could be motivation for change. However, patients should also be encouraged to find support within themselves (19). The following are the five stages of change: (19)

- Stage 1: the pre contemplation phase; they do not believe they have a problem. They are not thinking of making changes in their lives or considering how the substance may be harming them.

- Stage 2: the individual begins contemplating the need for change. They begin to realize that the substance is affecting them. This is a great time for providers to encourage them to keep contemplating and consider making a change by identifying the pros and cons of using the substance.

- Stage 3: the preparation phase; the patient has made the decision to change. More encouragement is needed. Healthcare providers should assist patients in planning and providing resources.

- Stage 4: the patient makes the change. They may start decreasing the use of substances or stop using them completely. The best thing to do for the patient is to be as supportive as possible. Patients should develop strategies on how to say “no” to situations regarding the substance.

- Stage 5: the patient is maintaining the change. Patients should focus on the positives of not using the substance and their achievements during this process.

Providers should be honest with patients regarding relapse. Recovery from substance abuse is not a linear path that is 100% successful. Everyone has moments of relapse when it comes to new habits, and it should not be discouraging. Remind patients that there is always help from providers who are non-judgmental.

Treatment strategies can include managing withdrawal symptoms in the acute phase, remaining in treatment, and preventing relapses. Many psychotherapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy can be very beneficial for recovery from substance abuse. Twelve step facilitation programs are twelve weekly sessions done individually that prepare patients for twelve step mutual support programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotic Anonymous. While these support programs are not treatments, they are beneficial as additional support to other treatments.

Contingency management programs are similar to a rewards program. Patients, families, friends, or providers may offer rewards or privileges for meeting certain requirements of substance abuse recovery. These requirements might be taking medications as prescribed, participating in sessions, or remaining free of the substance. Rewards can be decided upon by the patient in collaboration with family, friends, and providers (26).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What services does your facility, organization, city, county provide for substance abuse recovery?

- What services that are offered are beneficial to those that need them?

- Do you believe there are enough resources available? If not, what services do you think are still needed?

- Does your facility have funding for additional services or patients?

- How can you advocate for additional services to be offered?

- Of the five steps of change, which step do you think is the most difficult? Provide your rationale.

- Think back on a patient you had that was in the midst of recovery. What stood out to you about them?

Safety Planning Strategies and Monitoring the Usage of the Safety Plan

Active suicidal ideation and behaviors are considered a medical emergency and should be treated accordingly. Providers in the emergency department setting should focus on medical emergencies and treatments first before moving on to any mental health treatments or consultations (19). Since suicide can be prevented, it is the duty of healthcare providers to ensure the patient is in a safe environment.

Ensuring safety can encompass a variety of methods. One example is searching belongings to remove any weapons or items that can be used to harm the individual or others such as lighters, shoelaces, strings from hoodies, and medications.

Patients may be placed under various observation statuses based on orders made by the physician or a mid-level provider. These observation statuses are also based on facility policies and best practices guided by evidence. Patients withdrawing from substances may need to be closely monitored on a medical floor due to worsening signs and symptoms. Seizures can be life-threatening for these patients.

Restraints and/or seclusion may be required as a last resort for patients. Per Washington law, patients must be under a one-to-one status, meaning there is one staff member always observing the patient. Observation can be done via audio and video equipment, or in-person. There must be documentation discussing the patient’s behavior and condition, attempts for a least restrictive method of treatment, response to seclusion and/or restraints, and the need to continue seclusion and/or restraints. A face-to-face assessment must be performed by a trained professional within one hour of the patient being placed in restraint or seclusion (38).

General regulations for restraints and seclusion include: (38)

- Within one hour of seclusion and/or restraints being initiated, an order from the physician must be entered.

- The nurse must communicate with the family or patient’s legal caregiver regarding the restraints and or/seclusion and the process that will be followed.

- The nurse must discuss with the patient the need for seclusion and/or restraints and attempt to get cooperation from the patient.

- There is to be support from others to assist with the seclusion and/or restraint process.

- Continuous observation is to be maintained while the patient is in seclusion or restraints.

- Physical and psychological needs must be addressed at regular intervals.

- The nurse is responsible for documenting the need for seclusion and/or restraints and patient assessments.

- The nurse is required to maintain education and competence on restraints.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Do you know what your facilities policies and procedures regarding seclusion and restraints? Do you know where to locate these policies and procedures?

- Some facilities have a no-restraint policy. Does your facility currently have a similar policy, or is that something you think could be advocated for?

- Based on your role, what are your responsibilities when it comes to seclusion and restraints?

- Who in your facility can apply restraints on patients?

- What is your confidence level with applying restraints?

- If you are not confident in applying restraints what are your resources to gain confidence?

- Who are the individuals that are able to monitor patients when they are in seclusion or restraints?

Obtaining Support and Engagement from Third Parties

As reflected in this course, family and friends are vital supportive factors for the individual with suicidal ideation or attempts. If the patient is willing, education should be given to their support system so that everyone understands medications, treatments, follow-up and outpatient treatment, and what to do in another crisis resulting in a suicide attempt or exacerbation of suicidal ideation.

Case Study Reflection 6

Courtney is a 25-year-old female patient who is at your facility with her husband. She was discharged from the hospital a few weeks ago for an aborted suicide attempt. Her friend found her overdosed in the bathroom of her house. She was given follow-up with your facility. Now that she is with you, she reports that she would like resources to help her cope better. After being told she has a history of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, you begin to think of resources and treatment you can offer her.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Who else can support Courtney during her recovery?

- How can you ask Courtney about her support system and their involvement in her care?

- Thinking back to the beginning of the course, what protective factors can you give Courtney and her support system?

- Would you consider recommending or ordering any medications for Courtney at this time?

- When would you like to follow-up with Courtney? Would you like anyone else to come to the next appointment?

- Are there any goals you can give Courtney that she can work towards prior to your next appointment?

Restricting Access to Lethal Means

Statistics report that 55% of those that attempt suicide use firearms, 26% use suffocation, and 12% use poisoning. The last 8% is classified as “other” (8). Reducing or limiting access to lethal means can be defined as increasing the distance between someone with suicidal ideation and lethal means. An example would be to have the patient give their firearms over to another responsible adult that lives over 30 minutes away (12).

All providers should discuss this information with their patients and their support systems. By reducing access to lethal means, it is possible to decrease rates of suicide. However, providers must be aware that patients may not tell the full truth when it comes to availability of lethal means, and restricting access is only part of treatment and care (12).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Does your facility, city, county, or state have any requirements for reporting lethal means within the household?

- Are there any states that you know of that report lethal means in the household?

- If not, would you consider “reporting accessibility to lethal means” as a good idea to implement?

- How could you advocate for reporting to your government officials?

Transition of Care: Discharge and Referrals for Continuity of Care

Treatment of the patient who has suicidal ideation or had a suicide attempt does not stop once they leave the hospital setting. Care must be continued outside of the hospital setting through outpatient psychiatric providers such as a psychiatrist or psychiatric nurse practitioner. These providers can prescribe medications, adjust treatments, and provide additional therapy referrals that may be beneficial for the patient. These psychiatric providers should collaborate with the patient’s primary care provider. As discussed previously, certain psychiatric medications can interact with medication for medical diagnoses.

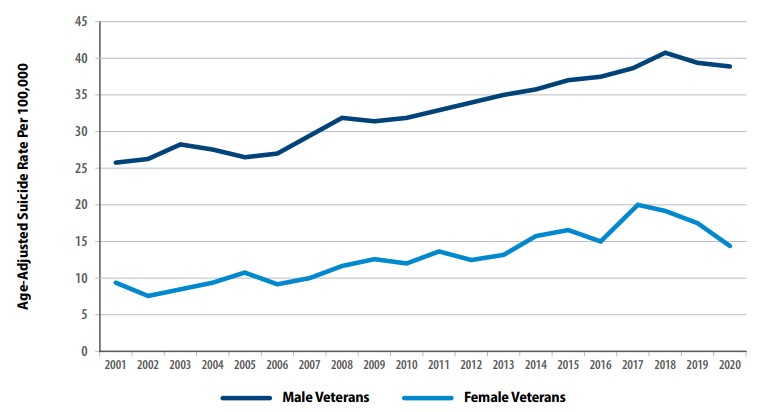

Veteran Populations

Data from 2020 reports that there were over six thousand veteran suicides in the United States, an average of 17 veterans dying by suicide each day. Substance use and mental health prevalence among those using the Veterans Health Administration rose from 27.9% to 41.9% from the years 2001 to 2020 (14). These numbers are staggering as veterans have a 1.5 higher risk of suicide than those in the general population and women Veterans have a suicide rate that is 2.5 times higher than civilian women (36). The chart below shows the suicide rates based on gender as classified by male and female [See figure 14].

Figure 14: Suicide Rates Among Veterans by Gender From 2001 to 2020 (36)

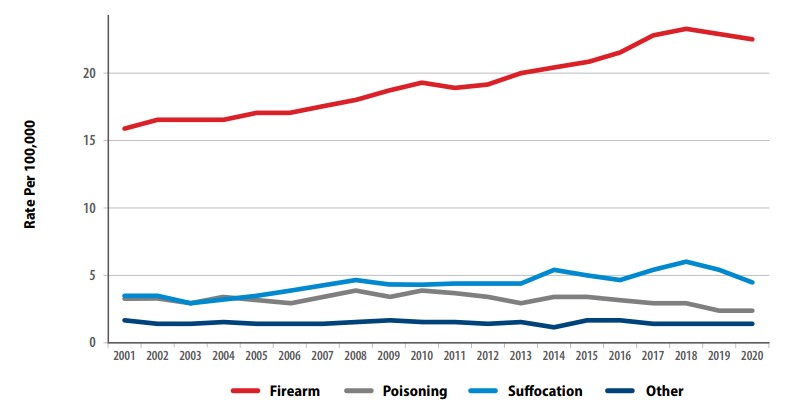

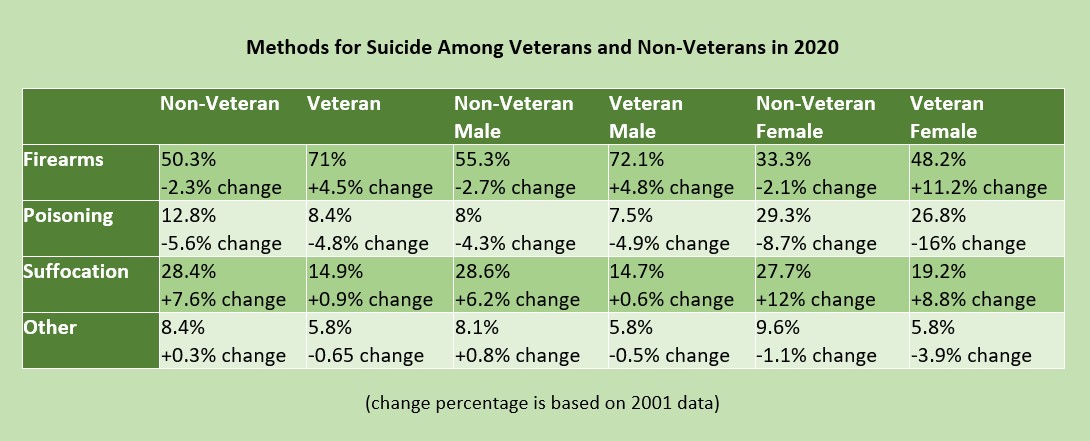

Rates of suicide were also affected by age. Veterans in the 18- to 34-year age range had a 95.3% increase between 2001 to 2020. Those aged 55 to 74 only rose to 58.2% during that same time period. From 2019 to 2020, older veterans’ suicide rates decreased while those in the 18 to 34 age group increased (14). As with the civilian population, methods of suicide were relatively similar; data was gathered from 2001 to 2020 [See figure 15]. Additionally, rates for suicide are higher among the veteran population in comparison to civilians; the change percentage is based on 2001 data [See figure 16].

Figure 15: Methods for Suicide Among Veterans from 2001 to 2020 (36)

Figure 16: Methods for Suicide among Veterans and Non-Veterans (36)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Of the statistics listed in the figure above, what surprised you the most?

- Do you agree with this data? Why or why not?

- Have you considered if this data is completely accurate? Do you think the data could be under- or over-reported?

- Does your facility or city have a large veteran population?

- If so, do you provide care to this population often?

Veterans have similar risk factors that have different causes from their civilian counterparts. They have complex mental health conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, manic-depressive disorder, and traumatic brain injuries as a result of combat exposure. Others have combat wounds that can lead to severe medical diagnoses and possible prescribing of opioid medications for controlling pain. Veterans may have insomnia which can exacerbate any of their other symptoms or diagnoses. These individuals may turn to substance abuse instead of other forms of treatment due to the ease of accessibility. Studies show that over one in 10 veterans are diagnosed with at least one substance use disorder. There is an increased risk of opioid overdose, but this population is more likely to turn to alcohol (36).

The Department of Veteran Affairs has taken steps to provide resources for mental health and suicide prevention to all veterans. Veterans and families are given suicide prevention education upon discharge, and suicide assessments are completed during every visit. Each facility has a Suicide Prevention Coordinator that can be contacted at any time. Veterans, and their families and friends can utilize Veterans Chat, a free, anonymous messaging service that gets them in touch with a Veterans Affairs counselor. If needed, the counselor can transfer the individual to the Veterans Crisis Line for further counseling or referral services (35).

Veteran Resources (All civilian resources are available to veterans):

https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/

https://www.va.gov/health-care/health-needs-conditions/mental-health/suicide-prevention/

https://theactionalliance.org/veteran-and-military-suicide-prevention-resources

Case Study Reflection 7

Cory is a 45-year-old male patient that presents to your emergency department for severe abdominal pain. During your initial assessment, Cory tells you he also feels dehydrated and has been more tired than usual lately. He says he ran out of his sleep medication, “but the providers at the VA are so hard to see. It takes months for an appointment.” When you ask him the standard questions (if he drinks alcohol or uses any other substances), he becomes angry and snaps at you before immediately apologizing. Cory admits that he has been drinking more than usual for the past few months because his chronic leg pain—an injury from when he was in combat—has been bothering him more than normal.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Would you perform a suicide screening on Cory? What is your rationale?

- If Cory admits to having suicidal ideation, what would be your next steps?

- If Cory denies suicidal ideation, but reports he’s been feeling hopeless or depressed, what would be your next steps?

- Does your facility have any resources to provide Cory while he is in the emergency department?

- Could you consider advocating for a collaboration with the nearest VA to assist veterans like Cory who come to your facility?

Suicide Loss Survivors

As highlighted throughout this course, suicide can happen to anyone, and they leave behind many people. Friends, families, coworkers, and acquaintances can all be affected by the loss. Those who have lost a loved one to suicide are often referred to as suicide loss survivors.

If a healthcare provider encounters a suicide loss survivor, they should always assess the risk for suicide. As discussed previously in this course, some individuals may attempt suicide on the anniversary of their loved one’s passing. In addition, they could attempt on a day of significance to the individual that passed or a major holiday that held special meaning. If the suicide loss survivor is at a high risk for suicide, follow your facility’s protocols for additional assessment or treatment (1).

If there is no significant risk for suicide, provide support and resources. Remember that some individuals have chronic suicidal ideation. Support can be through active listening, having a non-judgmental attitude that is free of bias or criticism. Some individuals may be hesitant to tell their story due to the nature of the loved one’s death. Encourage them to talk to someone they can trust if they do not want to share that information with you. Reassure them that bereavement is not a linear process and that they do not have a time limit to when they should be done grieving. Every person is different, and how they progress through the stages of grieving varies (1).