Course

West Virginia RN Renewal Bundle

Course Highlights

- In this West Virginia RN Renewal Bundle course, we will learn about best practices for managing patients who display drug seeking behaviors and diversion.

- You’ll also learn how to implement patient education taking into consideration different learning styles and individual preferences.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of how to identify and analyze quality improvement opportunities.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 12

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Patient Education Strategies

Introduction

As nurses, we wear many hats and take on numerous roles in our careers. The main part of our job is to educate our patients.

Have you ever walked into your patient’s room after the physician leaves, and are bombarded with questions from your patient? They are confused and scared, and this is when you come in.

Patient education is important in every type of nursing: inpatient, outpatient, acute care, long-term care, adults, or pediatrics. No matter the specialty of nursing, at some point in time you must educate your patients and their families.

This course’s goal is to provide resources to improve education for your patients, give strategies to prevent barriers to education and evaluate the effectiveness of the education we provide.

Definition- Patient Education

What does patient education mean exactly?

Education is knowledge that results from the process of being educated [10]. No matter what type of nursing you are in, you are constantly giving patients instruction on a topic.

Whether it is regarding medications, diagnostic testing, or diagnoses we are the patient’s main point of contact. A physician or provider is with a patient for a short amount of time, and it is our job to explain the information that was given to them.

Currently, there is information everywhere. We are almost overloaded with information. With the use of smartphones, we can search for almost anything.

Our patients, for the most part, want to feel in control of their health, and this can come in the form of knowledge. As soon as they hear something, they want to search for information on the subject.

This should not substitute our teaching. A lot of the information published may not be accurate or not pertain to their situation. We must be aware of this and make sure we are providing our patients with resources so they can find accurate information [2].

Who are we educating?

The Healthcare Education Association has shared guidelines on patient education [8]. In some instances, we are educating family members, caregivers, friends, and sometimes an entire family [8].

You might be caring for an elderly patient in an acute care setting and will be discharging this patient home to their adult child. They will now be the caregivers and they will require education. Or you are caring for a five-year-old, just diagnosed with type I diabetes in which multiple members of the family will need to be educated on carbohydrate counting and insulin administration.

During this course, the term patient education may be used but it is meant to encompass anyone that we are providing teaching to.

Importance

At the end of the day, patient safety is our main goal. Patient education is a vital way to promote patient safety.

After a new medication is prescribed, we must educate the patient on why they need to take this medication, how to take the medication appropriately, and the side effects of the medication. Our education can also push the importance of lifestyle changes after a diagnosis.

It is easy to go through the motions of your job and forget why we became nurses. Our patients need their healthcare team to take the time to explain the importance of their treatment plan. Education helps patients be the center of their healthcare [12].

What is health literacy?

Health literacy is described as the knowledge of health information and the ability to understand and find resources related to health information, to make decisions for their healthcare based on this information [1].

This definition was changed in 2020 [1]. The change included being able to use health information and apply it to their life, not just having the ability to understand the information. This new definition also states that organizations need to include health literacy in their mission statement [1].

A study conducted by the National Assessment of Adult Literacy showed that only 12% of adult Americans have the appropriate health literacy to understand their care and make informed decisions [7]. With the average population, there is an extreme deficit of the ability to have the information to make autonomous decisions for their healthcare.

How does health literacy play a role in education?

With understanding what health literacy means, we want to give our patients the most accurate information, so they can make the most informed decisions about their healthcare. As nurses, we should be aware of our patients’ health literacy and want them to have the highest level of information available.

Our goal should be that the patient understands and utilizes the information provided in their healthcare choices. Studies have shown that there is a correlation between low education and poor health status [4].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can nurses determine their patient’s health literacy?

- Can patient education cut healthcare spending costs?

- Who is responsible for funding patient education?

Role of Nursing

Whose role is it to provide patient education?

Sometimes education can be thought to fall under the physician’s scope of practice. However, every member of the healthcare team can play a part in educating our patients [8].

As said earlier, nurses usually spend the bulk of their time with patients. It is our duty to reinforce and expand upon the teaching provided by other members of the healthcare team. We also must collaborate with other members of the healthcare team to not leave gaps in the education that is provided [12].

Opportunities for Teaching

How should education be prioritized?

In nursing, we are expected to perform a variety of tasks. It can get overwhelming at times trying to prioritize and complete each task. Adding any other task to that list can be daunting.

Education should be incorporated into our work to place patient safety as the goal. Education should be prioritized over other tasks [13]. Many factors such as time and adequate staffing can result in insufficient education [13]. Simple tasks should be delegated if possible, so that you can focus on educating your patients.

Learning Styles

What are the main learning styles?

- Visual- A visual learner requires seeing what they are learning right in front of them [9]. They benefit from graphs and examples for them to look at. Not only going over the education but also providing them with a copy of the teaching is useful.

- Auditory- An auditory learner thrives on hearing the information [9]. This type of learner would not benefit from just receiving a pamphlet.

- Reading- This example of a learning style would be providing material for the learner to read on their own [9].

- Kinesthetic- This type of learner would be described as a “hands-on” learner [9]. This learner would benefit by tangibly holding material. When providing education about

changing an ostomy bag and giving them an ostomy bag to hold would be useful during the teaching.

How do we as nurses identify a patient’s learning style?

A barrier to education can be that we sometimes treat each patient the same. We build standardized educational pamphlets to provide to our patients, teach group classes, and provide similar, if not identical, resources.

While this can be helpful and save time, it can also be a barrier. Not all people learn the same way. Completing a learning assessment for each patient could help identify their preferred learning style to in turn make the teaching more effective [8].

How can we use learning styles in our teaching?

Each person may not be a single type of learner and may be responsive to a variety of learning styles. Prior to providing the actual education, it is important to determine which learning style the patient would be most receptive to.

Also factoring the subject matter into which style you use can be beneficial in teaching [9]. If you need to educate on how to change a dressing on a wound, a demonstration would be appropriate.

If you need to educate on dietary modifications for a low-cholesterol diet, a handout that can be referenced makes sense. The subject matter should be considered when determining which type of learning style should be used.

Case Study:

A patient is being discharged home with a diagnosis of asthma and a new prescription for an albuterol MDI as needed for wheezing. You are the nurse providing discharge teaching.

Prior to providing education you ask if the patient has a preferred learning style. The patient states they are a hands-on learner and are receptive to reading material.

When providing the teaching you give them a spacer with the inhaler to hold and demonstrate how to attach them together. You demonstrate how to administer the ordered number of puffs. You review and provide them with a printout of triggers that could exacerbate their asthma.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can multiple learning styles be utilized in your patient’s education?

- Does age play a role in learning styles?

- Can the patient’s education level be a factor in their learning style?

- What if the patient does not have a preferred learning style?

Teaching Strategies

What to include in your education plan?

Before beginning your education with the patient or family member you must set a plan. In your plan, you should include realistic information [2]. Stick to the need to know and not all the information you would like your patient to know [2].

Information overload can be a barrier to helping the patient understand what you are teaching them. In some specialties, nurses have multiple interactions with their patients, where they can build a rapport with them [12].

Use this to your advantage. It might take several visits with your patients to help them understand a certain topic. While other specialties such as acute care, the emergency department, or outpatient surgery centers need to provide concise information and additional resources so the patient can review the information at a later time [2].

Set an attainable goal for yourself and your patient. If you have a short amount of time, it is not realistic to expect to educate on an entire topic such as COPD and expect the patient to verbalize understanding. With specific attainable goals, this will help in your planning and execution of the teaching.

What to ask patients at the beginning of the teaching?

At the start of your teaching, it is crucial to ask the patient about their concerns [8]. A patient might be more receptive to the education if they feel like they are heard. Patient education should be patient-centered, which means focusing on their needs [8].

This can be useful information so you can include what they are most concerned about in the teaching. The patient will then feel valued and will be open to learning.

How does a learner’s demographic become a factor in their understanding of information?

A review was conducted regarding older adults and their preferred style of information [3]. This review concluded that older adults benefit more from written articles presented by healthcare professionals and were not as receptive to group classes, online apps, or videos [3].

Statistics from the CDC states that by 2030, 71.5 million people will be over the age of 65 living in the United States [6]. Which means, in order for them to lead healthy lives, it is our responsibility as healthcare workers to play our part in providing accurate information for them to implement in their lives [6].

On the other end of the spectrum, you might be educating a patient on the other end of the spectrum, a child. Pediatric nursing requires lots of education for the families and the patients themselves.

Children can learn and understand topics when they are presented with developmentally appropriate material. With pediatric patients props and hands-on learning can be beneficial. Age should be considered when planning education materials for patients or their families.

Language can also be a barrier to communication. It is important to ask a patient their preferred language for healthcare information. A patient may speak English however they might be more comfortable in their first language if it is something other than language.

Prior to teaching, a learning assessment is beneficial for you and the patient [8]. Asking the learner their preferred language should take place first.

A patient’s culture can also impact their learning abilities [5][8]. As health care providers we must not shy away from cultural differences but rather incorporate this in our practice [8]. The information we provide should be standardized with our patients, however the way we communicate can vary.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can your own culture become a barrier to patient communication?

- What is the best way to ask about a patient’s culture?

- When providing education to a patient who speaks a different language than your own, can information be lost when utilizing an interpreter?

When is the appropriate time to educate your patient?

The patient may be in the middle of a life-changing event or managing a chronic disease and they may have a hard time focusing. When planning to educate a patient it is important to factor in the time of the education.

Did the patient just get out of surgery? Was the patient up all night? Involving the patient in the education will help the patient be more receptive and give them some control [2].

If the patient is being discharged and requires education set a time with them to go over the information. This can prevent barriers that might occur.

How can technology influence education?

In this day in age, technology has influenced all aspects of our lives. Technology can be incorporated into our education as well [2]. Many hospitals are using programs on patient televisions to provide education.

When planning to teach our patients we should explore these methods to help the patient and ourselves as the educator. Some videos can be used that explain procedures, skills, and medications to our patients [8]. It is also important to know our patients and see how receptive they are to this means of education.

An elderly patient may not be interested in a link for more education regarding dietary changes [3]. A person in their 30s may like education they can look at on their computer at home.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- When is providing a patient with a video for teaching appropriate?

- Can technology inhibit a patient from understanding the education provided?

Evaluating Effectiveness

What does it mean to evaluate your teaching?

Teaching is not complete until it is evaluated. As healthcare professionals, we must gauge if our teaching was understood or if further teaching is indicated [8].

If further teaching is needed, it does not mean we failed at our job. It means that we have our patient’s best interest, and we want them to succeed and need to change our education to fit their needs.

Studies in the past have shown that 40-80% of medical teaching done at an outpatient visit was not remembered by the patient and almost half of the information that was retained was not accurate [11].

What are some strategies to evaluate the patient’s understanding of the education provided?

- Demonstration- Often nurses must teach a patient to perform a skill, for example, check blood pressure with a blood pressure cuff, perform a blood glucose check, and administer a subcutaneous injection.

In this type of instruction, the nurse should begin by stating the objective to the patient, which is the skill that needs to be performed, and explain that the patient should return to demonstrate that skill to the nurse [8]. By stating this at the beginning, the patient will know they need to perform the skill at the end of teaching and not be caught off guard. This is also a way to evaluate the teaching [8].

When the patient returns and demonstrates this skill, the nurse can discuss ways they can improve the skill [8].

- Teach-back method- This is a strategy that includes teaching and then allows the learner/patient to demonstrate what they learned back to you [11].

This is an example of how to evaluate the level of the patient’s understanding [11]. Giving the patient time to verbalize what you are educating is a measurable way to evaluate the education that was provided.

A strategy to use the teach-back method is to teach in sections and then allow the patient to state in their own words what they learned in that section [11]. This helps break up the teaching and allows the patient to process the information [11].

Case Study

You are set to discharge a patient home that was hospitalized due to anaphylactic shock from a food allergy. They are overwhelmed by the amount of information they are receiving.

They are prescribed an Epi-pen in case of future reactions. To implement the teach-back method you can use a training Epi-pen to demonstrate how it works.

Then give the practice Epi-pen to the patient so they can hold the Epi-pen and apply the Epi-pen to themselves. Now the patient can feel more comfortable after practice, and you can evaluate if the teaching was understood.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can nurses use the return demonstration method in their practice?

- Is the return demonstration method appropriate for every patient?

- What are the next steps if a patient does not accurately demonstrate the skill you were teaching?

Case Study

A patient is diagnosed with hypertension and high cholesterol. As the nurse at an outpatient clinic, you are responsible for going over some lifestyle changes with the patient. You have listed some changes they should make in their diet.

In the middle of the teaching, you ask, “What are 3 dietary modifications you can implement into your daily life?” This helps the patient process the information and turn it into their own words.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can nurses use the teach-back method in their practice?

- What settings can the teach-back method be useful in?

When to allow questions during teaching?

Sometimes it might feel easier for us to instruct the learner to save their questions till the end of the instruction. However, allowing the learner to ask questions throughout the education can help prevent information overload and be helpful for you to evaluate your teaching [8].

Questions can allow you to tailor your education to focus on areas that the patient might need more information on [8]. The patient can emphasize their concerns by asking to hear more information on a certain aspect of what you have taught.

When preparing for education make sure that you insert breaks so the patient or family member can ask questions. This will help with their learning and can help you determine the effectiveness.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are signs that the patient is not understanding our education?

- If our patient is not grasping the teaching, does it mean our educational techniques fail?

- What is the next step if the patient does not understand our teaching?

Conclusion

To summarize the content of this course: Patient education should be specific, concise, tailored to your patient’s needs, and measurable.

You should present your patients with objectives at the beginning of your education so they will know what to expect to understand by the end of the teaching. Address any questions that the patient might have and allow the patient to provide you with feedback.

By providing intentional patient-centered education we can give our patients the tools they need to make informed decisions about their healthcare.

Nurse Burnout

Introduction

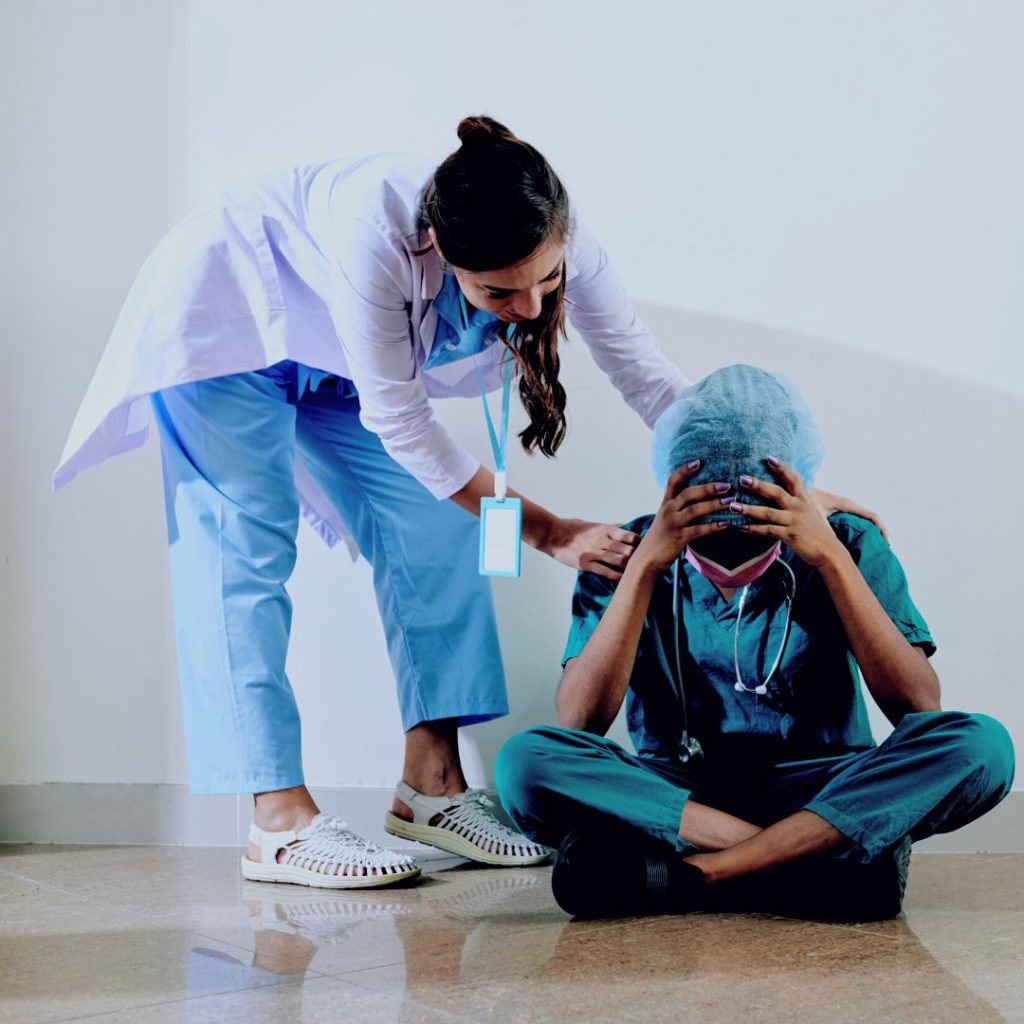

In May 2022, during Mental Health Awareness Month, the United States Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy issued a new Surgeon General’s Advisory highlighting the urgent need to address the health worker burnout crisis nationwide. Citing existing challenges in the healthcare system and the long-term effects of the coronavirus pandemic, Dr. Murthy prioritized our healthcare workers' mental health to strengthen our nation’s public health infrastructure.

This report stated that “…. up to 54% of nurses and physicians, and up to 60% of medical students and residents, suffering from burnout”. Symptoms of burnout have indeed impacted the current workplace, and ongoing employee mental and physical exhaustion results in a vulnerable, compromised workforce (2).

The lingering effects of post-pandemic burnout have affected every element of our current healthcare system. Healthcare professionals are leaving the profession at an alarming rate (due to illness and scheduled retirement), which translates to increasing shortages of providers. Coupled with additional vacancies due to ongoing mental health conditions (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder), our healthcare system is experiencing significant gaps in its ability to provide quality care across the healthcare spectrum.

While the legislature addresses healthcare burnout on a larger scale, nurse professionals owe it to themselves to recognize the signs and symptoms of nurse burnout and take appropriate action to protect themselves, their families, colleagues, and patients.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why do you think the coronavirus pandemic caused such large numbers of healthcare worker burnout?

- How do you think the coronavirus pandemic affected your place of employment?

- What difference did the pandemic make in your specific job responsibilities?

Nurse Burnout vs. Compassion Fatigue

Although the terms “nurse burnout” and “compassion fatigue” are often used interchangeably, they do refer to two separate conditions (4). Nurse burnout is the term used to describe emotional and physical exhaustion related to ongoing stressful working environments and associated responsibilities. Burnout has a gradual onset and usually occurs in behaviors such as decreased workplace productivity and persistent feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and overwhelming exhaustion.

Compassion fatigue, on the other hand, often emerges from some prolonged emotional stress or strain. It may occur after exposure to a traumatized individual more so than a workplace trauma. Signs and symptoms of compassion fatigue may manifest in such behaviors as anger, irritability, increased anxiety, and physical exhaustion. In comparing burnout to compassion fatigue, burnout appears to gradually rise to the surface, while compassion fatigue occurs more suddenly (5).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Regarding compassion fatigue, what situations could make a healthcare professional “angry, irritable, and exhausted” while on duty?

- Regarding nurse burnout, what situations could make a healthcare professional feel “hopeless and helpless” while on duty?

Life As a Nurse

An average day in the life of a nurse will include varying degrees of stress and long work hours. Both factors are known to affect one’s mental health, yet it is considered “a normal day’s work” when describing a day in the life of a nurse.

In any workplace setting, a nurse's role includes a very demanding set of acceptable stressors (“part of the job”). Upon completing a highly stressful workday, nurses may head home to face additional demands on their time and energy levels (child/elder care, various household responsibilities, and community and church obligations, to name a few). This routine leaves little time for rest and recovery, both mind and body.

All those demands on their time and attention can lead to compassion fatigue. The pandemic is a convincing example of both nurse burnout and compassion fatigue. Nursing professionals were repeatedly exposed to critically ill patients, many of whom did not survive. Staffing patterns were suboptimal, critical care beds and equipment were sorely lacking in some areas, and the daily stressors felt during a single shift seemed to repeat themselves. There was no quality “downtime” for nurses to take a well-deserved break, much less debriefing and regrouping/refocus efforts.

This pandemic, a universal “once in a lifetime” event by any standard, affected everyone at some level. Nurse professionals were witnessing traumatic losses of life every day. Compassion fatigue, understandably so, began to surface. The healthcare community experienced anger, irritability, and increasing levels of anxiety. They took to the news media, voicing feelings of isolation, despair, anger, and devastation. They publicly spoke of sleep difficulties, increased workloads, and lack of appropriate lifesaving supplies, thus becoming more exhausted and cynical with each passing shift. When the pandemic crisis finally came under control, the landscape of nursing looked quite different (6).

Nurses had resigned, transferred, or walked off their shifts. Early retirements and medical leaves of absence were increasing in number. Enrollments in nursing schools were down. The healthcare arena continues to suffer years later, looking for solutions to “heal thyself.”

So, the question remains…. What can we do to reduce the risk of nurse burnout moving forward?

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you describe your current workplace?

- Do you feel appreciated for your efforts while at work?

- What is one “major stressor” you wish to change at your workplace?

Burnout Risk Factors

While no single factor causes nurse burnout, there are undoubtedly identifiable risk factors and patterns that heighten the risk. Early identification and intervention of such risk factors lower the chances of nurse professionals suffering personally and professionally.

Increased workloads (due to staff call-ins, lack of patient care equipment, and lack of ancillary help) are a leading causative factor in nurse burnout. In addition, lack of support from senior leadership, unit managers, worksite colleagues, and other members of the organizational healthcare team impacts feelings of helplessness and hopelessness.

Again, there is no single factor to point blame at, but there are often patterns of behavior that warrant further investigation at the workplace. In addition, nurse burnout is very individualized. What is harmful and hurtful to one nurse may not be seen as such to another nurse.

The goal is to make the workplace environment supportive for all employees by creating (and nurturing) a culture that welcomes nursing input. By recognizing the bigger picture of individual and organizational safety, the nurse in crisis feels safe in stepping forward and seeking professional help in a supportive environment.

While nurse burnout can occur in any area of nursing, from hospitals to clinics to home health settings and beyond, some areas are at higher risk for burnout. Nursing professionals in the intensive care and emergency care units are at higher risk for symptoms of burnout.

Studies have shown that many specialty nurses experience anxiety, increasing exhaustion, and mounting frustration while on duty. Combined with a patient population often experiencing high rates of trauma-related mortality and complex illnesses, it is understandable that “typical workdays” may be filled with extremely high levels of workplace stress.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Think about your current workplace. Are there any factors that could contribute to burnout?

- Have you witnessed anyone in your workplace display signs of being “burned” out?

Causes of Burnout

An article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association identified some causes that directly impact nurse burnout (7). The authors found that nurses who routinely worked longer shifts (extra shifts, mandated overtime shifts) and experienced sleep deprivation exhibited symptoms of burnout. The combination of excessive work hours and inadequate sleep (as often occurred with shortened turnaround times and back-to-back shifts) resulted in increased patient care errors. These occurrences often compounded the feelings of helplessness and hopelessness (8).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever picked up extra shifts only to regret it afterward?

- How did you feel after working those extra shifts?

Impact on (Individual) Health

In the early stages of burnout, the nurse professional may feel overworked, underappreciated, and physically tired. While such symptoms may appear benign when occurring sporadically and “chalked up” to “just having a bad day,” repeated shifts like this may manifest into a more profound feeling of despair.

It soon becomes challenging to continue working under such circumstances, further escalating the situation. To distance oneself from these feelings, the nurse professional may become cynical and jaded about their workplace, mentally distancing themselves from colleagues. These efforts only serve to isolate the individual further and exacerbate feelings of hopelessness and isolation while negatively impacting workplace efficacy (9).

Impact on Workplace/Organization Health

The stressed out, overworked, and exhausted nurse professional may unknowingly / unintentionally compromise the quality of care. Feelings of helplessness and hopelessness can negatively affect the nurse’s judgment and critical thinking skills. Critical steps/tasks may be skipped when the nurse is tired and overworked.

Nurse burnout negatively impacts job satisfaction and, in doing so, also negatively impacts patient care. The effect will be poor patient care, increased patient and family complaints, and poorer patient outcomes. Nurse burnout affects not only the individual but the organization. (10)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How does a nurse unintentionally compromise the care being delivered to a patient?

- How do you think being sleep-deprived could affect your abilities while on duty?

Self-Care Strategies

“I have come to believe that caring for myself is not self-indulgent. Caring for myself is an act of survival.”

— Audre Lorde (3).

What is self-care? (12)

In the most basic definition, self-care refers to doing things that will improve your physical and mental health. It is very subjective, and self-care strategies must focus on your needs, wants, and desires. As stated, nurse burnout is very individualized: what profoundly affects one nurse may not even bother the next nurse.

The strategies discussed here are generic; they must be personalized to fit your specific needs and healing process.

- A good night’s sleep: Limit caffeine intake before bedtime, no electronics 1-2 hours before sleep, lower room temperature to facilitate comfortable sleep, and blackout curtains.

- Physical activity: Light-impact activities such as swimming, yoga, walking, bike riding, and other activities will be physically and mentally beneficial.

- Diet: Maintain a balanced diet. Monitor hydration levels and limit caffeine products. The goal is to nourish your body to offset the adverse effects of stress. Cut down on processed food intake and “junk foods.”

- Mental health: Journaling, podcasts, music, and joyful hobbies and activities (knitting, crafts, painting).

- Homefront Maintenance: Calm surroundings foster the healing process. Keep the environment clean, uncluttered, and welcoming. Empty the sinks and dishwashers, fold the laundry, and make your bed. Aromatherapy, lighted candles, and essential oils are all ways to make your home a place to rest and relax.

The list of “self-care “strategies is endless. Be sure to find an appropriate diet, activity, and behaviors that enable you to focus on building a balanced lifestyle.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some self-care strategies that have worked in your personal life?

- How could you encourage a nursing colleague to “take better care of themselves” through self-care practices?

Organizational Strategies

Healthcare organizations must provide structured support for their nurse professionals to ensure quality patient care. Facility-wide strategies work best to identify and treat nurse stress and burnout early.

- Nursing rounds- routinely meet with nursing staff and listen to their feedback. Ask the difficult questions (staffing patterns, scheduling issues) and be receptive to working on viable solutions.

- Support staff in utilizing earned days off, vacation time/ paid time off.

- Open lines of communication with staff experiencing signs of nurse burnout or compassion fatigue. Offer alternate job duties and work assignments if possible.

- Acknowledge employee organizational loyalty (through retention bonuses, additional days off, gift cards, personalized thank-you letters, and personal development endeavors).

- Encourage critical debriefings for staff members involved in essential/traumatic patient care encounters.

- Openly promote facility resources available to staff, including all Employee Assistance Programs.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do you feel your healthcare organization could improve the current workplace?

- What are some employee assistance programs currently offered at your workplace?

- What incentives/ acknowledgments from your nurse leaders would most benefit staff morale?

Case study

Marie is a 35-year-old Registered Nurse working full-time on a 16-bed ICU unit. She has been employed here for three years, beginning her employment at the start of the coronavirus pandemic. Marie works 12-hour shifts (7p-7a) with every other weekend off. Two of Marie’s nurses' coworkers recently resigned, leaving the unit chronically short-staffed.

Marie has been working additional shifts to help her coworkers and has just completed a 50-hour work week. She was once again called into work early and arrived on only 4 hours of sleep the night before. The unit is at total capacity with 2 “ICU holds” in the Emergency Department. Marie has fallen behind on her patient care while intercepting repeated calls from the ED staff.

Marie spent a long overdue break crying in the nurse's lounge. She confided to another staff member (Anne) that she is exhausted and overwhelmed by these work conditions and is considering resigning. Anne told Marie to take a few more minutes for her break and promised to discuss the situation with their charge nurse, Carol. Marie agreed.

Anne discussed the situation with Carol, stating Marie is a great nurse who has been working too many shifts lately. Anne offered to pick up some of Marie’s current patient assignments to lower Marie’s stress level, hopefully. Carol approved and also took some of Marie’s patients. Marie finished her break, apologized to her coworkers for her “moment of weakness,” and promised, “it wouldn’t happen again.”

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What factors did you identify that put Marie at risk for nurse burnout?

- If Marie confided in you, as a colleague, that she was exhausted and overwhelmed, how would you respond?

- Marie apologized for her “moment of weakness” and promised “it wouldn’t happen again.” How would you respond to this employee if you oversaw this shift?

- What resources are available at your current workplace for employees who acknowledge they are “exhausted and stressed out”?

- If you were the Nurse Manager of this ICU, what would you do to support your staff during this time (* significant staffing shortages due to recent resignations)?

Resources

The following links are provided for additional information on nurse burnout surveys.

Conclusion

The healthcare workforce continues to be challenged by large numbers of scheduled retirements, an aging population, and medically complex patients. Nurse leaders must proactively hire and retain a healthy workforce (13). Healthcare organizations must invest in a workplace culture that supports workers' work/life balance. It is the key to ensuring the health and safety of our nation.

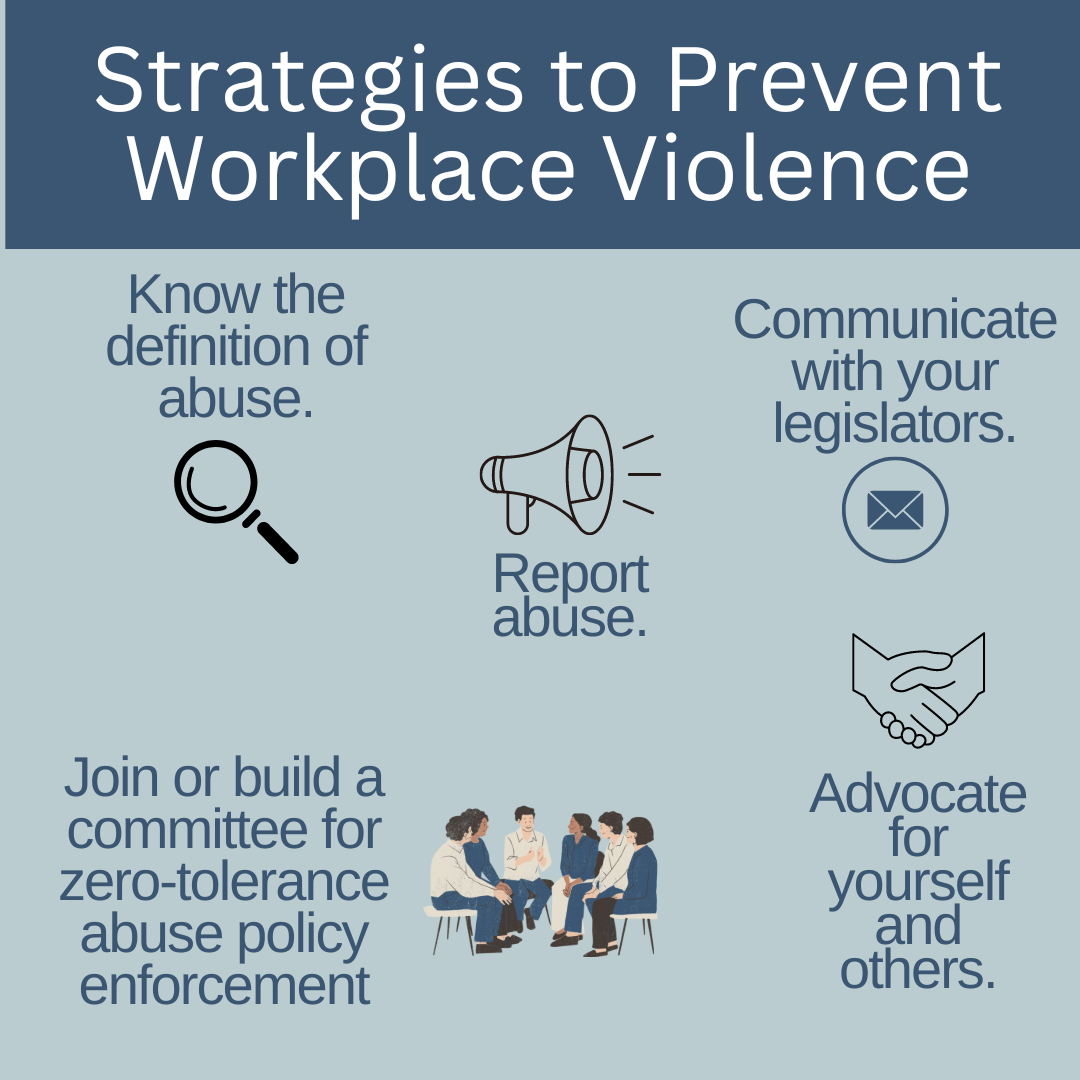

Bullying in Nursing

Introduction

In a time when bullying has become one of the most frowned upon behaviors, why is it thriving in the world of nursing? We’ve all heard the saying that “nurses eat their young”. It is a term that has been passed down the nursing ranks as each generation of nurses enters the workplace; unchanged and still true. We, as nurses, cannot permit such unhealthy and detrimental behavior to continue. In this course, we will discuss nurse bullying, why it happens and what we can do to break the curse.

Definitions

To fully understand nurse bullying and the issues that come with it, we must define some terms and phrases so that we are all on the same page.

Nurse Bully

A nurse bully is someone who repeatedly harasses and/or harms other nurses whom they believe they can dominate; they may also see them as less skilled or incompetent (5).

Incivility

Incivility is a type of lower-level bullying that entails more passive types of behavior. This is your mocking, gossiping, alienation, and general rudeness. The difference between incivility and actual bullying is that incivility may not actually harm the victim (6).

Harassment

Harassment is when someone torments or intimidates another person (4).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is the difference between incivility and bullying?

- Who is the victim of the nurse bully?

Incidence Rate

The nursing profession has historically been known as the most trusted profession. Nursing is also synonymous with caring and compassion. From the outside looking in, it may be difficult to believe that bullying could exist in such a respected and revered profession. The prevalence of bullying in nursing is staggering. Both new and seasoned nurses; young and old; nurses of every gender; and nurses of every walk of life report that they have been bullied on the job. These instances represent a wide variety of bullying behaviors which include verbal abuse, threatening, scapegoating, sabotage, and physical abuse (5).

Incidence rates of bullying in nursing, as documented in a variety of studies, ranging from 17-85%. This includes incidents of verbal abuse, threatening, belittling, and even physical abuse. With the prevalence of bullying so high among nurses, it is safe to say that virtually every nurse has been touched by bullying, whether victim, perpetrator, or observer (5).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Does the incident rate of nurse bullying surprise you?

- Have you ever witnessed or been involved in an incident of nurse bullying?

Why Does It Occur?

What drives bullying behaviors? What makes a bully? There are a myriad of factors that come into play when discussing why bullying occurs.

Anger and frustration are two strong emotions that can contribute to bullying behaviors. In today’s nursing work environment, anger and frustration are at the forefront of many nursing units. Nursing shortages have left many units understaffed and the nurses overworked. This frustration leads to anger when the nurses who have remained loyal, full-time staff see travelers come into their areas making higher pay. Lack of resources and the belief that they are unheard of also contribute to feelings of frustration (5).

The belief that another nurse is less competent or altogether incompetent can also lead to bullying. When it is perceived that another nurse can’t do their job and therefore may leave tasks for the oncoming shift, the above-mentioned frustration sets in and bullying may result. Just the feeling of superiority over another nurse can have bullying effects on the nursing environment (1).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Is there a key risk factor that promotes an environment of nurse bullying?

- Are nurse bullying risk factors real or perceived? Explain.

Risk Factors

There are some circumstances that contribute to the bullying climate. These are not excuses that give permission to the bullies, rather they are risk factors that have been identified as possible catalysts to bullying behaviors.

Seniority

Some nurses may feel that they have “paid their dues” and should have authority over their less-experienced peers. If this authority is not granted, the senior nurse may harbor feelings of underappreciation and lash out by being unhelpful or, to the extreme, harmful. The aim is to show how much this nurse is needed; they will refrain from helping the newer nurse or giving any advice (5).

Insecurity

When new nurses come into the workplace, the existing nurses may feel that they will be replaced. Nursing is an ever-evolving occupation with new technologies and treatments being developed all the time. A new nurse who was taught the most up-to-date trends in nursing may pose a threat to their job. This is when the nurse may start to bully the new nurse joining the team (1).

Protection

Some nurses become very attached to their patients. They may feel that no one else can give the same level of care that they can. As a result, they may see other nurses as incapable of providing care that is up to their standards. Only they can provide the care that their patients require. These perceived inadequacies can quickly turn into bullying behaviors (1).

Education

Differences in levels of education may also contribute to bullying. Nursing has many different levels of education and nurses from all these levels may work together on a single unit. Nurses with higher levels of education may feel superior and lash out at those with less education. RNs may treat LVNs differently than their RN peers (3).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Name 2 risk factors that contribute to nurse bullying.

- Have these risk factors led to a nurse bullying environment in your organization?

- Does one risk factor stand out to you as a prime contributor to nurse bullying?

- Which one?

Types of Bullying

It is important to note that not every bullying-type behavior can be construed as actual bullying. We all have bad days when things just don’t seem to be going right and we may react inappropriately. One of the key factors that differentiates bullying from a lapse in judgment is that bullying is a repeated or habitual behavior.

This does not excuse the one-time behavior however, we must realize that not all poor behaviors are bullying. Nurse bullying may manifest itself in a variety of different behaviors. Below, we will discuss a few of these types of bullying. This is by no means an exhaustive list of all possible bullying behaviors; they are some of the behaviors that you may commonly see in the healthcare environment (5).

Verbal abuse

This may include being rude, belittling, criticizing, and threatening. We’ve all heard “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me”. This is a false saying as constant verbal abuse plays with our psyche as we rerun the taunts in our heads over and over. If heard enough, we may start to believe the bully’s words.

Controlling

Constantly telling another nurse what to do and how to do it. This is unsolicited advice that if not taken may escalate bullying behaviors. Controlling behaviors may also include certain “looks” and intimidating posturing.

Ignoring/excluding

Ignoring requests for help. Ignoring any suggestions to better provide care to the patients. Excluding that one nurse from lunch plans, work-related activities, or any after-work gatherings.

Assigning heavy workloads

Repeatedly assigning a nurse a heavy workload while everyone else’s load is relatively light. All the other nurses have time to sit and document while the one nurse is overwhelmed.

Physical abuse

Unwanted physical contact is usually violent in nature.

Mobbing

This happens when a group of bullies band together to create an environment to force the victim to resign (2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you witnessed any of these behaviors at your organization?

- Is there a behavior that is most indicative of nurse bullying?

- What is the key aspect that makes these behaviors acts of bullying?

Characteristics of a Nurse Bully

Nurse bullies come in all shapes and sizes and come from all walks of life. There isn’t necessarily a template for what a nurse bully will look like. However, there are some characteristics that may help identify a nurse bully.

You may encounter a nurse who bullies out of a sense of superiority. They will be condescending and have an entitled attitude. You will also recognize them by their “correcting comments” often spoken where others can hear. Next, we have nurses who bully because they have been offended by something said or done. They bully with an ax to grind. They may hold on to the grudge for a long time. Creating drama with the victim at the center will be their course of action; they will try to pull in other nurses to help ostracize their victim. Other nurse bullies will use rumors and gossip to bully their victim (3)

These bullies love to dish out the put-downs but can’t take any back. They will become offended at the slightest criticism. There are others who will be very friendly at first. Bringing the victim in close to learn details of their lives and then using that information against them. They will weaponize all obtained information to lift themselves up. Another characteristic is envy. There are those bullies who are envious of others. The envy could stem from something totally unrelated to nursing or the workplace. The victim, however, will most likely possess the item or characteristic that the bully is envious of. This bully is very bitter. Finally, there is the bully who plays favorites. They will favor their clique and ignore or exclude the victim (3).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Do you recognize these characteristics in the nurses you work with?

- Do you see any of these characteristics in you? How will you change?

What Can You Do?

There are many actions that you can take when you are either the witness or victim of nurse bullying. Though some bullies may be intentionally trying to intimidate a fellow nurse, there are those who are oblivious to the fact that they are bullies. They behave like a bully without knowing that they are perceived as such.

The first action that you may want to take is to talk with the bully about the behavior. The bullying may end there. Once it has been brought to the bully’s attention that the behavior is being taken as bullying, change can occur. Communication may be all that is needed (5). Prior to speaking with the bully, try using empathy. Put yourself in the bully’s shoes to figure out what the motive for the behaviors may be. This may aid you in both the tone and direction of the conversation.

Identifying a mentor in the workplace can also help you through a bullying situation. Having someone that you can talk to about the issue and seek their advice about how to handle the situation. Look for those nurses who can’t be bullied. Why do the bullies not prey on them? Why are they not intimidated? Often, these nurses are focused on the patient’s needs above all else and refuse to allow any situation to be about them or the bully (3).

Talking with your manager or director is another prudent course of action. It is possible that these nurse leaders have the best vantage point to deal with and prevent nurse bullying. They work closely with the front-line staff nurses and should have the pulse of the unit. In their position of authority, they are also able to investigate and, if needed, conduct disciplinary actions.

Unless your manager or director is the bully, a meeting with them to discuss any instances of bullying is needed. Contacting the Human Resources department is another step that can be taken. No matter the situation, it is always important to follow your facility’s policies and procedures and chain of command (3).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What can you do to prevent/stop nurse bullying in your organization?

- What organizational resource should you use to guide your actions?

Solutions to Nurse Bullying

Nurse bullying has repercussions throughout the entire facility. According to a study from 2012, the cost for each individual who is bullied can be from thirty thousand to one hundred thousand dollars (3). This includes the cost of absenteeism, lower work performance, any therapies needed for physical and psychological issues, and increased turnover due to ongoing bullying.

Nurse bullying can also play a big part in the overall feeling of “burnout” among nurses. Nurse bullying can lead to workplace errors which means it is crucial that organizations have strategies to combat any kind of bullying in the workplace. As nursing accounts for the majority of employees at most hospitals, curbing nurse bullying should be in the forefront. Here are some organizational strategies that should be considered:

Culture of Safety

Many organizations have adopted a “Culture of Safety”. The Culture of Safety promotes patient and colleague safety. It is the shared beliefs and values of the organization that influence behaviors and actions. Principles such as non-punitive reporting, communication of policies and expectations, recognition, and leadership modeling of behaviors all come into play in the Culture of Safety. All reports of bullying should be taken seriously (3).

Admit that there is a problem

Like any issue, the first step in fixing it is admitting that the problem exists in the first place. Bullying thrives in the darkness. Once it is brought to light and people are talking about it, it can be addressed. Even if there is no evidence of nurse bullying in your area, talking about and discouraging it may stop it from even starting (3).

Elimination

Try to eliminate factors that promote an environment of bullying.

Commitment

The organization should commit to a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to bullying. The policy on bullying should outline clear expectations along with the consequences that will be enforced if the policy is not followed. The policy should also include the organization’s social and online media sites (3).

Accountability

Nurses should be encouraged to hold each other accountable. You promote what you permit. As there are generally more bullying witnesses than actual bullies, nurses must be empowered to call out bullying. This can lead to a true change in the culture of an organization (3).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Is your facility currently using any of the above-mentioned strategies?

- How have these strategies mitigated the incidence of nurse bullying in your area?

- Can an organization eliminate nurse bullying?

Conclusion

Nurse bullying is a real problem that can affect any unit in any hospital. It creates a toxic work environment that we, as nurses, can no longer tolerate. In this post-COVID time, nursing shortages and nurse burnout are rapidly depleting the nursing ranks. It is time for nurses to call out bullying when they see it. It is time for nurse leaders to enforce the organizational consequences of nurse bullying.

We must create safe environments for our new nurses (all nurses) to thrive. It is the only way that our profession will survive. Know the signs of nurse bullying and become the change within your organization. Empower your colleagues to do the same. Together, we can see an end to nurse bullying.

Quality Improvement for Nurses

Introduction

Welcome to the world of Quality Improvement (QI) in healthcare, a dedicated field committed to continually enhancing patient care and outcomes. Quality Improvement involves a systematic approach to identify, analyze, and address areas for improvement within healthcare processes, ultimately resulting in improved patient safety, satisfaction, and overall healthcare excellence (13). In this course, we will embark on a journey to explore the fundamental principles and practical applications of QI, explicitly tailored for nurses who aspire to make a positive impact in their healthcare settings.

As a nurse, you know the significance of providing high-quality patient care. However, you may wonder how you can actively contribute to improving the systems and processes in your workplace.

Imagine this scenario: You observe a recurring issue with medication administration, where doses are occasionally missed due to workflow inefficiencies. Through this course, you will acquire the knowledge and skills to apply QI methodologies like Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles to investigate such issues, implement changes, and monitor the impact of your interventions. By understanding QI principles and tools, you will be better equipped to collaborate with your colleagues, drive meaningful improvements, and ensure that your patients receive the best care possible.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can nurses leverage their unique position at the bedside to identify opportunities for quality improvement in healthcare settings?

- Can you provide an example from your own experience or knowledge where a quality improvement project led to tangible improvements in patient care?

- What potential challenges could a nurse encounter when attempting to implement quality improvement projects?

What is Quality Improvement?

Quality Improvement (QI) in healthcare represents an ongoing, systematic effort to elevate the quality of patient care and healthcare services that involves identifying areas needing improvement, implementing changes, and evaluating the effects of those changes to ensure better patient outcomes (12).

Let’s envision a scenario where a hospital's surgical department grapples with a higher-than-average rate of post-operative infections. Through a QI initiative, the healthcare team can meticulously scrutinize the surgical processes, pinpoint potential sources of infection, and introduce evidence-based practices such as enhanced sterilization techniques or more rigorous antibiotic prophylaxis protocols. Over time, they can gauge the effectiveness of these changes by monitoring infection rates for a reduction.

Commonly used QI methodologies in healthcare include the DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) process and the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. These approaches provide structured frameworks for healthcare professionals to tackle issues systematically and iteratively. For example, imagine a bustling primary care clinic with extended patient wait times.

Here, the PDSA cycle can come into play using the systematic iterative steps below:

- The team defines the problem (lengthy wait times)

- The team proceeds to test a change (for example, adjusting appointment scheduling)

- The team then scrutinizes the results and acts accordingly to refine the process.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How does the concept of Quality Improvement (QI) align with the goal to provide the best possible care for patients?

- Can you think of a specific healthcare scenario where QI methodologies like DMAIC or PDSA could significantly improve patient care?

- What are the advantages of using structured frameworks like DMAIC and PDSA in QI initiatives?

- How do DMAIC or PDSA contribute to the success of improvement projects?

History and Background of Quality Improvement

The history and background of Quality Improvement (QI) in healthcare have a rich and evolving timeline, dating back to the early 20th Century, with significant developments occurring over the years. One pivotal moment in this journey was the introduction of statistical quality control by Dr. Walter A. Shewhart in the 1920s (24). Dr. Shewhart's pioneering work laid the foundation for using statistical methods to monitor and enhance processes, a concept that would become integral to QI initiatives (24).

In the mid-20th Century, the contributions of Dr. W. Edwards Deming further propelled QI principles forward (7). Dr. Deming emphasized the significance of continuous improvement, active employee engagement, and process variability reduction. His ideas found fertile ground in post-World War II Japan, playing a crucial role in the nation's economic recovery and the emergence of renowned companies like Toyota, famous for its Toyota Production System (TPS), incorporating QI concepts (7).

Until today, QI has become indispensable to healthcare systems worldwide (16). To illustrate, envision a scenario where a hospital grapples with a high readmission rate among heart failure patients. By scrutinizing historical data and implementing evidence-based protocols for post-discharge care, hospitals can effectively lower readmissions, enhance patient outcomes, and potentially evade financial penalties under value-based reimbursement models (16).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How did the work of Dr. Walter A. Shewhart in the early 20th Century contribute to the foundation of QI, and how do statistical methods continue to play a role in healthcare improvement today?

- What fundamental principles were introduced by Dr. W. Edwards Deming, and how did they influence QI practices in healthcare and other industries?

- Can you provide an example of how QI methodologies, inspired by Deming's principles, have been successfully applied in modern healthcare settings to address specific challenges or improve patient care?

- How has continuous improvement evolved, and why is it considered a cornerstone of QI in healthcare?

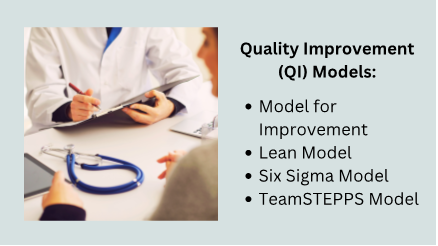

Models

At the heart of ongoing transformations in healthcare lies various Quality Improvement (QI) models. These models provide structured frameworks for identifying and addressing areas of improvement within healthcare systems (14). These models offer healthcare professionals a systematic approach to instigate meaningful process changes, ultimately resulting in elevated care quality. See some models below.

Model for Improvement

The Model for Improvement is a widely recognized and highly effective framework for Quality Improvement (QI) in healthcare. This is because it empowers healthcare professionals to systematically test and fine-tune their ideas for process improvement, ensuring that changes are grounded in evidence and proven effective (17).

The Model for Improvement offers a structured and systematic approach to identifying, testing, and implementing changes to enhance healthcare processes and ultimately elevate patient outcomes.

Developed by Associates in Process Improvement (API), this model revolves around the iterative "Plan-Do-Study-Act" (PDSA) cycle, which forms the foundational structure of QI initiatives (17). The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle is a systematic approach that guides healthcare teams through quality improvement, and it comprises the four key phases below, each contributing to developing and implementing meaningful changes in healthcare practices (12).

- Plan: In this initial phase, healthcare teams define the specific problem they aim to address, set clear and measurable goals, and craft a comprehensive plan for implementing the proposed change. For instance, if a hospital seeks to reduce patient wait times in the emergency department, the plan may involve adjustments to triage protocols or streamlining documentation processes.

- Do: Once the plan is established, the proposed change is implemented, typically on a small scale or within a controlled or pilot environment. This enables healthcare professionals to assess the feasibility and potential impact of the change without making widespread adjustments.

- Study: The study phase involves rigorous data collection and analysis to evaluate the effects of the change. In our example, the hospital would measure the impact of the new triage protocols on wait times, closely examining whether they have decreased as expected.

- Act: Based on the findings from the study phase, the healthcare team makes informed decisions about the change. They may adopt the change if it has successfully reduced wait times, adapt it further for enhanced effectiveness, or, if necessary, abandon it.

The PDSA cycle's iterative nature means adjustments can be made, and the cycle repeats until the desired improvement is achieved (12).

Lean Model

The Lean model, initially conceived in the manufacturing sector, has found considerable success and applicability in healthcare as a potent tool for process enhancement and waste reduction (22). At its core, Lean thinking revolves around the principles of efficiency and value optimization because it focuses on refining processes to eliminate wasteful elements while simultaneously delivering care of the highest quality (22).

Healthcare organizations have adopted Lean methodologies to tackle many challenges, from reducing patient wait times to improving inventory management and elevating overall patient satisfaction (22). For instance, when a hospital is challenged with prolonged wait times in its outpatient clinic, it can apply Lean principles to systematically analyze the patient flow, pinpoint bottlenecks, and streamline processes.

This might involve reconfiguring furniture to enhance flow, adjusting appointment scheduling, or implementing standardized work procedures. The ultimate objective is to cultivate a patient-centric, efficient environment that ensures timely access to care while meticulously conserving time and resources.

Another integral aspect of Lean thinking is the unwavering commitment to continuous improvement and the pursuit of perfection through the systematic identification and eradication of various forms of waste (19). The forms of waste are often categorized into seven types: overproduction, waiting, unnecessary transportation, overprocessing, excess inventory, motion, and defects (19). By keenly identifying and addressing these forms of waste, healthcare organizations not only enhance the utilization of resources but also curtail costs and elevate the overall quality of care delivery.

Six Sigma model

The Six Sigma model is a robust and widely adopted healthcare method for improving processes and reducing mistakes (9). It was first used in manufacturing but is now used in healthcare to make processes more consistent and improved by finding and fixing mistakes and inefficiencies (9).

An example is when a hospital is concerned about the accuracy of medication dosing for pediatric patients, a Six Sigma team might include: indicating the problem, gathering data on mistakes regarding dosing, and finding out why the mistakes happened. The strategy may encompass the implementation of standardized dosing protocols, refining staff training programs, and closely monitoring the medication administration process to ensure that mistakes are eliminated.

Six Sigma uses a framework called DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) to make improvements. This framework utilizes data-driven tools to discern problems, quantify their origins, develop practical solutions, and institute control mechanisms to sustain improvements (11). Through this systematic journey, healthcare organizations position themselves to deliver care of elevated quality, curtail costs, and bolster patient safety.

TeamSTEPPS model

TeamSTEPPS, which stands for Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety, is a teamwork and communication model designed explicitly for healthcare settings (4). Developed by the U.S. Department of Defense and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), TeamSTEPPS focuses on improving patient safety by enhancing team collaboration, communication, and decision-making among healthcare professionals (4).

One key element of TeamSTEPPS is using structured communication techniques to prevent errors and misunderstandings. For instance, during patient handoffs from one healthcare provider to another, TeamSTEPPS emphasizes using a structured tool like SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) to convey critical information succinctly and accurately. This ensures that essential patient details are noticed, reducing the risk of adverse events (18).

In a surgical team scenario, TeamSTEPPS principles can be applied to improve teamwork and communication among surgeons, nurses, and anesthesiologists. The model encourages briefings before procedures to set clear objectives, huddles during surgery to address emerging issues, and debriefings afterward to reflect on the process and identify areas for improvement. By fostering a culture of open communication and mutual respect, TeamSTEPPS contributes to safer, more efficient healthcare delivery (4).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can healthcare organizations determine which QI model suits their specific challenges or improvement goals?

- How do QI models emphasize data collection and analysis, and why is this critical in healthcare?

- Can you imagine a real-world scenario where the Lean Six Sigma framework can successfully improve healthcare processes and outcomes?

- What are some emerging trends or innovations in QI models and methodologies, and how might they shape the future of healthcare quality improvement?

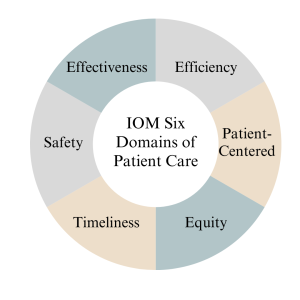

IOM Six Domains of Patient Care

The Institute of Medicine (IOM), now known as the National Academy of Medicine, introduced the Six Domains of Quality in Healthcare as a framework to assess and improve the quality of patient care (14). These domains, introduced in 2001, encompass various aspects of care delivery and patient experience, helping healthcare organizations and providers identify areas for improvement (14). The domains serve as pillars for assessing the different dimensions of care delivery, ensuring that healthcare organizations and providers address the holistic needs of patients (14).

Definitions

The Six Domains of Patient Care are essential for providing high-quality healthcare. See definitions of each of the IOM's six domains of patient care below.

- Safe: Safety is the foundational domain, emphasizing the importance of reducing the risk of patient harm. This includes preventing medical errors, preventing infections, and ensuring the safe administration of medications. Healthcare organizations implement safety protocols and engage in continuous monitoring to minimize risks (14).

- Effective: Effective care ensures that patients receive evidence-based treatments and interventions that result in the desired outcomes. It involves using the best available scientific knowledge to make informed decisions about patient care avoiding unnecessary or ineffective treatments (14).

- Patient-Centered: Patient-centered care focuses on individualizing healthcare to meet each patient's unique needs and preferences. It involves respecting patients' values and preferences, engaging them in shared decision-making, and delivering care with empathy and compassion (14).

- Timely: Timely care emphasizes reducing delays in healthcare delivery. It includes providing care promptly and avoiding unnecessary waiting times for appointments, tests, and treatments. Timely care is especially critical in emergencies (14).

- Efficient: Efficiency in healthcare means maximizing resource utilization and minimizing waste while providing high-quality care. This domain emphasizes streamlining processes, reducing unnecessary costs, and optimizing healthcare resources (14).

- Equitable: Equitable care underscores the importance of providing healthcare that is fair and just, regardless of a patient's background, socioeconomic status, or other factors. It aims to eliminate healthcare access and outcomes disparities among different patient populations (14).

Measures

Measures in the context of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) six domains of patient care refer to the metrics and indicators used to assess and evaluate the quality of care provided in each domain. According to (14), the measures below are essential for monitoring and improving healthcare services. See details below.

- The "Safe" domain measures focus on tracking and reducing adverse events and medical errors. Key indicators include rates of medication errors, hospital-acquired infections, falls, and complications from procedures. Safety measures also assess the implementation of safety protocols, such as hand hygiene compliance and patient identification bracelets.

- Measures in the "Effective" domain assess how evidence-based practices and treatments are utilized. These measures include adherence to clinical guidelines, appropriate use of medications, and the success rates of medical interventions. Additionally, outcomes such as patient recovery, remission, or improvement are indicators of the effectiveness of care.

- The "Patient-Centered" domain focuses on assessing the patient’s experience and satisfaction with care. Patient surveys and feedback are standard measures, evaluating aspects like communication with healthcare providers, involvement in decision-making, and overall satisfaction with the care received. Healthcare organizations also measure shared decision-making and respect for patient preferences.

- Measures related to the "Timely" domain evaluate the efficiency of healthcare delivery. Key metrics include waiting times for appointments, diagnostic tests, and procedures. Additionally, measures track the timely delivery of urgent care and the avoidance of unnecessary delays in treatment.

- Efficiency measures aim to quantify resource utilization and the reduction of waste in healthcare. Metrics may include the cost of care per patient, length of hospital stays, and resource allocation efficiency. Improvement in resource utilization and cost-effectiveness are vital indicators of efficiency.

- Measures within the "Equitable" domain assess disparities in healthcare access and outcomes among different patient populations. Healthcare utilization and outcomes data are stratified by demographics, socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity to identify and address inequities. Key indicators include access to preventive care, healthcare utilization rates, and health outcomes across various demographic groups.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can healthcare providers ensure their care aligns with patients' values, preferences, and cultural backgrounds?

- What challenges might patients face in accessing healthcare services, and how can healthcare organizations improve access for all patients?

- What are the potential consequences of poor care coordination among healthcare providers, and how can interdisciplinary teams work together to enhance coordination?

- Why must healthcare organizations continually assess and improve the quality of care they provide, and what mechanisms can be implemented to support ongoing improvement efforts?

Nursing Quality Indicators

According to (5), nursing quality indicators are essential metrics used to evaluate and improve the quality of nursing care in healthcare settings. These indicators provide valuable insights into nursing practice and patient outcomes, helping healthcare organizations and nursing staff deliver safe, effective, patient-centered care. Let's delve into some key nursing quality indicators and their significance below.

Patient Falls

Patient falls are a critical quality indicator in nursing care since they can result in severe injuries and complications for patients (5). As a result, healthcare organizations measure and monitor the rate of patient falls to identify trends and implement preventive measures.

For example, when a hospital notices an increase in the rate of falls among elderly patients in a particular unit, they may introduce interventions such as nonslip flooring, improved lighting, and patient education as fall prevention strategies to reduce the incidence of falls.

Medication Administration Errors

Ensuring accurate medication administration is crucial in nursing practice because medication errors can lead to adverse events, including patient harm or death (5). Nursing quality indicators related to medication administration errors include the rate of medication errors and adherence to medication reconciliation processes (5). For instance, nurses are encouraged to verify patient allergies and cross-check medication orders to prevent errors. If there is an increase in medication errors in a healthcare facility, it may prompt a review of medication administration protocols and additional staff training.

Pressure Ulcers (Bedsores)

Pressure ulcers are a quality indicator of patient skin integrity since they develop when patients remain immobile for extended periods (5). As a result, healthcare organizations measure the incidence and prevalence of pressure ulcers as an indicator of the quality of nursing care (5).

Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction is a patient-centered nursing quality indicator since it reflects the overall patient experience and perception of care (5). Surveys and feedback mechanisms are used to measure patient satisfaction. For example, a scenario might involve patients receiving post-discharge surveys that assess various aspects of their hospital experience, including nurse responsiveness, communication, and pain management. Healthcare organizations can use this feedback to identify areas for improvement and enhance patient-centered care.

In summary, nursing quality indicators encompass a range of metrics that evaluate nursing care quality, patient safety, and patient experiences. By monitoring and responding to these indicators, healthcare organizations and nursing staff can continuously improve their quality of care, leading to better outcomes and increased patient satisfaction (5).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why is data collection critical in nursing quality improvement efforts?

- What types of data should nurses prioritize collecting to assess patient safety?

- How can nurses ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data they collect for quality improvement purposes?

- What challenges might nurse face when collecting patient-related data, and how can these challenges be overcome?

Data Collection

Quality improvement data collection is a critical component of healthcare quality initiatives, providing the necessary information to assess the current state of care, identify areas for improvement, and monitor progress over time (2). Accurate and meaningful data collection enables healthcare organizations to make informed decisions, implement evidence-based interventions, and ultimately enhance patient outcomes. Let's explore the methods of data collection below.

- Clinical Outcome Collection: Clinical outcome data collection is essential for assessing the effectiveness of healthcare interventions (2). For example, consider a scenario where a hospital is implementing a quality improvement project to reduce surgical site infections (SSIs) following orthopedic surgeries. Data collection would involve tracking the number of SSIs occurring over a specific period and collecting information on patient characteristics, surgical techniques, and post-operative care protocols. By analyzing this data, the healthcare team can identify trends, risk factors, and areas for improvement, ultimately leading to targeted interventions to reduce SSIs.

- Patient Satisfaction Survey Data Collection: Patient satisfaction surveys are valuable tools for collecting data on patient experience (2). A primary care clinic that aims to improve patient satisfaction may administer surveys to patients after each visit, asking about aspects of care such as communication with healthcare providers, wait times, and overall experience. The collected data can reveal areas of strength and areas requiring improvement. For instance, if survey results consistently indicate longer-than-desired wait times, the clinic can adjust scheduling practices or implement strategies to reduce wait times and enhance patient satisfaction.

- Process Measures Data Collection: Process measure data collection focuses on evaluating the efficiency and effectiveness of healthcare processes (2). For instance, in a medication reconciliation scenario, a healthcare organization might collect data on the accuracy and completeness of medication lists during care transitions. By tracking the frequency of medication reconciliation discrepancies, they can identify process inefficiencies and implement standardized protocols for reconciliation, leading to safer care transitions and reduced medication errors.

- Adverse Event Reporting Data Collection: Adverse event reporting is a crucial mechanism for collecting data on incidents that result in patient harm or near misses (2). For example, consider a scenario where a nurse administers the wrong medication dose to a patient but catches the error before any harm occurs. Reporting this near-miss event allows the healthcare organization to investigate the root causes, implement preventive measures, and share lessons learned with the care team to prevent similar incidents in the future.

Types of Data

Data types play a crucial role in understanding the current state of care, identifying areas for improvement, and implementing evidence-based interventions (2). Let’s explore the different types of data used in quality improvement below.